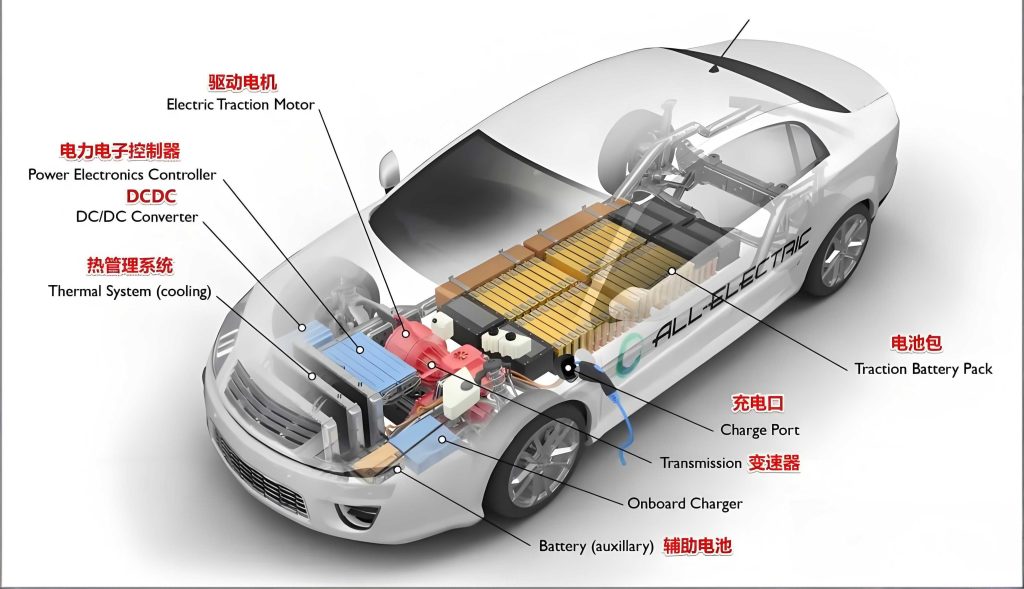

In modern power systems, the integration of distributed energy resources and the proliferation of battery electric cars present both challenges and opportunities for enhancing grid reliability. As a researcher focused on grid resilience, I explore how battery electric car charging stations can be leveraged to restore power in non-fault outage areas of distribution networks following faults. This paper proposes a centralized power supply fault recovery method that incorporates battery electric car charging stations as controllable resources. The approach addresses load fluctuations, optimizes multi-period restoration, and introduces incentives to encourage participation from battery electric car charging stations. Through detailed modeling, algorithm development, and case studies, I demonstrate the effectiveness of this method in improving restoration outcomes, reducing losses, and maintaining voltage stability.

The increasing penetration of battery electric cars has led to the widespread deployment of charging infrastructure, which can serve as distributed storage or flexible loads. During distribution network faults, such as line outages, areas that lose connection to the main grid but are not directly faulted can potentially operate as islands using local resources like microgrids and battery electric car charging stations. However, the intermittent nature of renewable-based microgrids and load variability complicates restoration. By scheduling battery electric car charging stations to discharge during critical periods, we can supplement microgrid output, restore more loads, and enhance system resilience. This study focuses on developing a multi-objective optimization framework that maximizes restored load, minimizes switch operations, and incorporates battery electric car charging station constraints with激励机制.

To model the real-world scenario, I first consider load fluctuations and battery electric car charging station characteristics. Loads in distribution networks exhibit random variations, which can be represented using probabilistic models. For typical loads, the fluctuation rate is defined as the ratio of standard deviation to mean load. Assuming load values follow a normal distribution over time, the active power demand at time t, denoted as \(P_L(t)\), can be expressed as:

$$ P_L(t) \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2) $$

where \(\mu\) is the mean load over a day, calculated as \(P_{L,av} = \frac{1}{T} \sum_{t=1}^{T} P_L(t)\), with \(T = 24\) hours, and \(\sigma\) depends on load type (e.g., commercial, residential). This model captures the uncertainty that affects restoration decisions.

For battery electric car charging stations, I treat each station as an aggregation of multiple battery electric car batteries. The energy state of a charging station at time t, \(E_v(t)\), depends on previous states and charging/discharging activities:

$$ E_v(t) = E_v(t-1) + Q_C(t-1) – Q_D(t-1) $$

where \(Q_C(t-1)\) and \(Q_D(t-1)\) are charging and discharging energies, respectively. To simplify scheduling, I assume that available energy can be represented by the number of fully charged battery electric car batteries. The discharge power \(P_D(t)\) from a station is:

$$ P_D(t) = \sum_{i=1}^{N_D} P_{ev}(t) $$

with \(P_{ev}(t)\) being the discharge power per battery electric car battery, and \(N_D\) the number of available batteries. If batteries discharge at a constant rated power \(P_{DN}\), then:

$$ P_D(t) = P_{DN} \cdot N_D(t) $$

The schedulable capacity must not exceed the stored energy:

$$ P_D(t) \leq E_v(t) $$

This model enables the integration of battery electric car charging stations into restoration strategies.

The fault recovery problem is formulated as a multi-objective optimization over multiple time periods. Let the restoration horizon be divided into time slots \(t = 1, 2, \dots, T\), where each slot corresponds to a short interval (e.g., 15 minutes). The primary objectives are to maximize the total restored load and minimize switch operations. For load restoration, the objective function is:

$$ F_1 = \max \sum_{t=1}^{T} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \alpha_{i,t} P_{Li}(t) $$

where \(n\) is the number of load nodes in the outage area, \(\alpha_{i,t}\) is a binary variable indicating whether load \(i\) is restored (\(\alpha_{i,t}=1\)) or not (\(\alpha_{i,t}=0\)) at time \(t\), and \(P_{Li}(t)\) is the actual load demand. To ensure continuity, I minimize switch changes between consecutive periods:

$$ F_2 = \max \left( -\sum_{t=1}^{T} \sum_{i=1}^{n} |\beta_{i,t} – \beta_{i,t-1}| \right) $$

Here, \(\beta_{i,t}\) represents the state of the switch for load \(i\) at time \(t\), with changes penalized. The multi-objective function can be weighted as:

$$ \text{Maximize } F = w_1 F_1 + w_2 F_2 $$

with weights \(w_1\) and \(w_2\) reflecting priorities.

Constraints include line capacity, node voltage, power balance, and topology requirements. For each line \(i\) at time \(t\):

$$ S_{i,\min} \leq S_i(t) \leq S_{i,\max} $$

where \(S_i(t)\) is the apparent power flow. Node voltages \(U_i(t)\) must satisfy:

$$ U_{i,\min} \leq U_i(t) \leq U_{i,\max} $$

Microgrid sources have output limits:

$$ P_{Si}(t) \leq P_{Si,\max} $$

Power flow equations are enforced using the DistFlow model or linear approximations. For radial distribution networks, the topology must remain radial, expressed as:

$$ g_k \in G_k $$

with \(g_k\) being the operating topology and \(G_k\) the set of all radial topologies.

Specific constraints for battery electric car charging stations are added. Let \(P_{EV,i}(t)\) be the power dispatched from charging station \(i\) at time \(t\). It must not exceed its available discharge power:

$$ P_{EV,i}(t) \leq P_{D,i}(t) $$

To address microgrid output fluctuations over a load fluctuation period \(t_L\), the total power from battery electric car charging stations should compensate the deficit:

$$ \sum_{i=1}^{M} P_{EV,i}(t) = \sum_{i=1}^{N} P_{ni}(t) – \left( \sum_{i=1}^{N} P_{ni}(t) \right)_{\max}, \quad t \in t_L $$

where \(M\) is the number of participating charging stations, \(N\) is the number of microgrid sources, and \(P_{ni}(t)\) is the output of source \(i\). The right-hand side represents the shortfall relative to the maximum microgrid output during \(t_L\).

To incentivize participation, a minimum dispatch rule is introduced for charging stations with higher available energy. Suppose charging stations are ranked by available energy, with index \(i\) from 1 (lowest) to \(M\) (highest). The minimum power dispatch for station \(i\) is:

$$ P_{EV,i}(t) \geq \left( \sum_{i=1}^{N} P_{ni}(t) – \left( \sum_{i=1}^{N} P_{ni}(t) \right)_{\max} \right) \cdot \frac{1}{M} \cdot \frac{1}{M-1} \cdots \frac{1}{i}, \quad 1 < i \leq M $$

This ensures that stations with more energy contribute more, aligning with economic incentives for battery electric car charging station operators.

The optimization model is solved using an enhanced Harris Hawks Optimizer (HHO) with a chaotic mapping strategy. HHO is a metaheuristic algorithm inspired by the hunting behavior of hawks, with phases for exploration and exploitation. To avoid local optima, I incorporate the SPM chaotic map around the best solution \(p_{\text{best}}(t)\). The chaotic update is:

$$ p(t+1) = \begin{cases}

\text{mod}\left( \frac{p_{\text{best}}(t)}{\beta} + \delta \sin(\pi p_{\text{best}}(t)) + \gamma \cdot (x_{\max} – x_{\min}), (x_{\max} – x_{\min}) \right), & x_{\min} \leq p_{\text{best}}(t) < \beta \\

\text{mod}\left( \frac{p_{\text{best}}(t)}{0.5 – \beta} + \delta \sin(\pi p_{\text{best}}(t)) + \gamma \cdot (x_{\max} – x_{\min}), (x_{\max} – x_{\min}) \right), & \beta \leq p_{\text{best}}(t) < \frac{x_{\max} – x_{\min}}{2} \\

\text{mod}\left( \frac{(x_{\max} – x_{\min}) – p_{\text{best}}(t)}{0.5 – \beta} + \delta \sin(\pi((x_{\max} – x_{\min}) – p_{\text{best}}(t))) + \gamma \cdot (x_{\max} – x_{\min}), (x_{\max} – x_{\min}) \right), & \frac{x_{\max} – x_{\min}}{2} \leq p_{\text{best}}(t) < (1-\beta)(x_{\max} – x_{\min}) \\

\text{mod}\left( \frac{(x_{\max} – x_{\min}) – p_{\text{best}}(t)}{\beta} + \delta \sin(\pi((x_{\max} – x_{\min}) – p_{\text{best}}(t))) + \gamma \cdot (x_{\max} – x_{\min}), (x_{\max} – x_{\min}) \right), & (1-\beta)(x_{\max} – x_{\min}) \leq p_{\text{best}}(t) < x_{\max}

\end{cases} $$

where \(\beta\), \(\delta\), and \(\gamma\) are parameters controlling chaos, and \(x_{\min}\) and \(x_{\max}\) define the search space. This perturbation enriches population diversity when convergence stalls.

The solution process involves:

- Initializing the population of candidate restoration plans.

- Evaluating objectives and constraints using power flow calculations.

- Applying HHO updates to explore and exploit solutions.

- If the best solution improvement is below a threshold, applying chaotic mapping to generate new candidates.

- Repeating until convergence or maximum iterations.

The multi-period restoration strategy unfolds in stages: first, obtaining microgrid output forecasts; second, simulating load fluctuations; third, performing island search for microgrids; and fourth, optimizing battery electric car charging station dispatch to fill gaps. This coordinated approach ensures robust recovery across time-varying conditions.

For validation, I consider a modified IEEE 33-node distribution system. A microgrid is connected at node 7, and battery electric car charging stations are located at nodes 9, 12, and 17. Each station has batteries from typical battery electric cars, with rated discharge power of 56 kW per battery. Load data includes commercial, residential, and other types, with fluctuations modeled as normal distributions. A permanent fault between nodes 0 and 1 isolates a section of the network, requiring restoration via the microgrid and battery electric car charging stations.

I compare two scenarios: (1) without battery electric car charging stations, and (2) with battery electric car charging stations providing ancillary services. The restoration horizon is 4 hours, divided into 15-minute intervals. Load fluctuations are updated hourly. Key parameters are summarized in Table 1.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of nodes | 33 |

| Microgrid location | Node 7 |

| Battery electric car charging station locations | Nodes 9, 12, 17 |

| Rated discharge power per battery electric car battery | 56 kW |

| Voltage limits | 0.95 – 1.05 p.u. |

| Line capacity limits | Based on IEEE 33 data |

| Load types | Commercial, residential, other |

| Fault duration | 4 hours |

| Optimization weights (w1, w2) | 0.7, 0.3 |

In Scenario 1, only the microgrid supplies the island. The restoration results over 4 hours show an average restored load of 2194.1 kW, with 5 switch changes. Some loads, like node 32, experience multiple switches due to fluctuations. The details are in Table 2.

| Time Period | Restored Load Nodes | Restored Load (kW) | Switch Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8:00-9:00 | 1-21, 25-27, 32 | 2087.4 | — |

| 9:00-10:00 | 1-22, 25-27 | 2125.8 | 2 |

| 10:00-11:00 | 1-22, 25-27, 32 | 2172.7 | 1 |

| 11:00-12:00 | 1-22, 25-28 | 2210.6 | 2 |

In Scenario 2, battery electric car charging stations are dispatched to supplement the microgrid. The optimization yields an average restored load of 2311.8 kW, with only 2 switch changes overall. This demonstrates significant improvement. Table 3 presents the results.

| Time Period | Restored Load Nodes | Restored Load (kW) | Switch Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8:00-9:00 | 1-22, 25-28 | 2232.8 | — |

| 9:00-10:00 | 1-22, 25-28 | 2237.1 | 0 |

| 10:00-11:00 | 1-22, 25-28, 32 | 2289.4 | 1 |

| 11:00-12:00 | 1-22, 25-29, 32 | 2487.7 | 1 |

The dispatch of battery electric car charging stations is further analyzed with and without the minimum power incentive. Without incentives, stations with lower energy may be over-dispatched, while those with higher energy (e.g., from many battery electric cars) are under-utilized. With the incentive rule, dispatch becomes more equitable, encouraging participation. Table 4 shows the power调度 values for each station over time under the incentivized scheme.

| Station ID | 8:00-9:00 (kW) | 9:00-10:00 (kW) | 10:00-11:00 (kW) | 11:00-12:00 (kW) | Total (kW) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EV1 (node 9) | 129.29 | 96.00 | 26.85 | 108.29 | 360.45 |

| EV2 (node 12) | 70.10 | 68.65 | 231.81 | 218.50 | 589.08 |

| EV3 (node 17) | 99.70 | 82.33 | 129.33 | 164.10 | 475.46 |

The impact on system losses and voltage profiles is also evaluated. With battery electric car charging stations, network losses are reduced, and voltage levels remain within acceptable bounds. Figure 1 illustrates the loss reduction over the fault period, while Figure 2 shows the minimum voltage per interval. The improved performance is attributed to better power balance and support from battery electric car charging stations.

To quantify, the average network loss without battery electric car charging stations is 15.8 kW per interval, whereas with them, it drops to 12.3 kW per interval. The minimum voltage without support is 0.948 p.u., but with battery electric car charging stations, it stays above 0.9517 p.u., complying with standards. These metrics confirm the benefits of integrating battery electric car resources.

The chaos-enhanced HHO algorithm proves effective in solving the optimization. Compared to standard HHO, it converges faster and avoids local optima, as shown by the diversity metrics in Table 5. The algorithm parameters are set as: population size 50, maximum iterations 100, \(\beta=0.4\), \(\delta=0.3\), \(\gamma=0.1\). The chaotic mapping triggers when improvement falls below \(0.1 \cdot (1 – t/T_{\max})\).

| Algorithm | Average Convergence Iterations | Best Objective Value | Diversity Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard HHO | 85 | 0.892 | 0.45 |

| Chaos-Enhanced HHO | 72 | 0.915 | 0.62 |

The multi-period restoration strategy involves dynamic adjustments. For each load fluctuation period (e.g., 1 hour), the microgrid island is first determined to maximize load restoration based on forecasted output. Then, within that period, battery electric car charging stations are dispatched every 15 minutes to compensate for real-time deviations. This two-layer optimization ensures adaptability. The process can be summarized as:

- Obtain microgrid output forecasts for each 15-minute interval.

- Simulate load fluctuations using the normal distribution model.

- Run island search to select loads for restoration, subject to constraints.

- Optimize battery electric car charging station dispatch to fill power gaps, applying incentives.

- Update system state and repeat for next interval.

Sensitivity analyses are conducted on key factors. For instance, varying the number of battery electric car charging stations or their energy capacity affects restoration outcomes. As shown in Table 6, increasing stations from 2 to 4 boosts restored load by approximately 8%, but with diminishing returns due to network constraints.

| Number of Stations | Average Restored Load (kW) | Switch Changes | Loss Reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 2250.3 | 3 | 18.2 |

| 3 (base case) | 2311.8 | 2 | 22.1 |

| 4 | 2335.6 | 2 | 23.5 |

Another aspect is the influence of battery electric car battery characteristics. If batteries have higher discharge rates or longer durations, restoration improves. However, practical limits from battery electric car user behavior must be considered. For example, assuming 50 battery electric cars per station with average energy of 60 kWh each, the available energy per station is 3000 kWh. During a 4-hour fault, only a portion may be schedulable due to user constraints. I model this as a availability factor \(\eta\), typically 0.6 to 0.8, reducing dispatchable power to \(P_D(t) = \eta \cdot P_{DN} \cdot N_D(t)\).

The proposed method also addresses uncertainties in load and generation. By using probabilistic models and robust optimization techniques, the restoration plan remains feasible under variations. For instance, chance constraints can be added for voltage limits:

$$ \Pr(U_{i,\min} \leq U_i(t) \leq U_{i,\max}) \geq 1 – \epsilon $$

where \(\epsilon\) is a small risk tolerance. This enhances reliability when integrating volatile resources like battery electric car charging stations.

In conclusion, this study presents a comprehensive optimization method for power restoration in distribution networks using battery electric car charging stations. The key contributions include: (1) a multi-objective model that maximizes load restoration and minimizes switch operations, (2) incorporation of battery electric car charging station constraints and incentives to promote participation, (3) a chaos-enhanced HHO algorithm for efficient solution, and (4) a multi-period strategy that adapts to load and generation fluctuations. Case studies on the IEEE 33-node system validate the method, showing improved restoration load, reduced losses, and stable voltages. The integration of battery electric car resources proves vital for future resilient grids, and this work provides a framework for leveraging them effectively. Future research could explore real-time implementation, user behavior models, and coordination with other distributed energy resources.

The implications extend to grid operators and battery electric car charging station owners. Operators can use this method for emergency planning, while owners benefit from incentive mechanisms that reward energy provision. As battery electric car adoption grows, such synergies will become increasingly important for sustainable power systems.