In the context of global energy crises and environmental degradation, the automotive industry has increasingly shifted toward hybrid electric vehicles as a mainstream solution for sustainable transportation. As an engineer involved in vehicle thermal management systems, I have focused on the integration challenges posed by hybrid electric vehicle powertrains, particularly the cooling system design. Unlike conventional internal combustion engine vehicles, hybrid electric vehicles incorporate additional components such as energy storage units, electric motors, and electronic control units, each requiring precise temperature control to ensure optimal performance and safety. This necessitates a dual-loop cooling system, featuring both high-temperature and low-temperature circuits, which introduces complexities in front-end cooling module layout. In this article, I will explore the design considerations for positioning a low-temperature radiator within the cooling module of a hybrid electric vehicle, with a primary emphasis on its impact on air conditioning refrigeration performance. Through a virtual design process that combines one-dimensional simulation and computational fluid dynamics analysis, I aim to balance development cost, schedule, difficulty, and performance to determine the optimal layout. The insights presented here are part of an integrated vehicle development approach, applicable not only to air conditioning systems but also to broader component and performance optimization in hybrid electric vehicles.

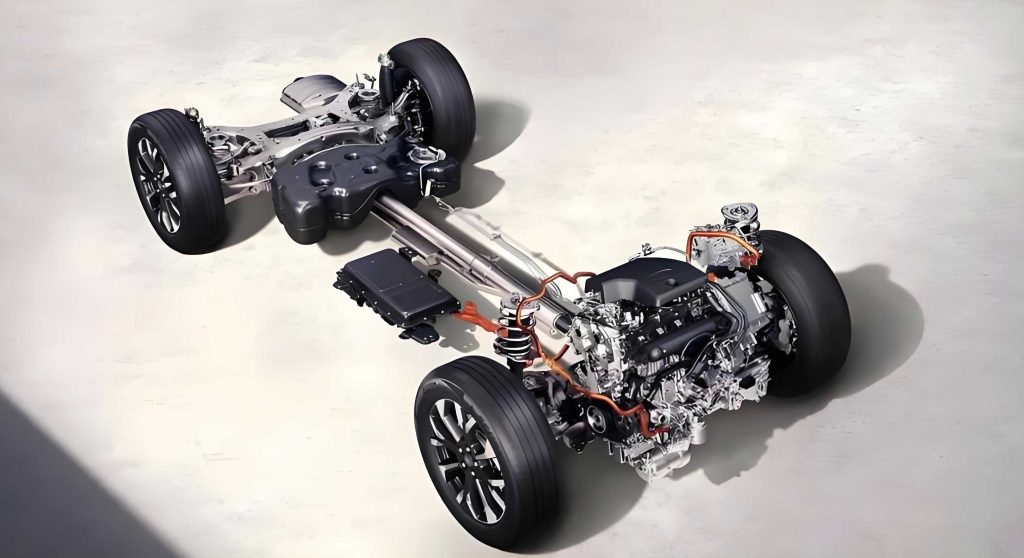

The cooling system in a hybrid electric vehicle is fundamentally different from that in traditional vehicles due to the diverse operating temperature ranges of its components. The internal combustion engine typically operates at coolant temperatures around 100°C, whereas electronic control units and electric motors in hybrid electric vehicles require lower temperatures, often below 65°C, to maintain efficiency and prevent overheating. To address this, a dual-loop cooling system is implemented, as illustrated in the conceptual diagram below. This system separates high-temperature heat sources (e.g., engine) from low-temperature heat sources (e.g., power electronics), with the latter cooled via a dedicated low-temperature circuit. A key element added to the front-end cooling module is the low-temperature radiator, which dissipates heat from the hybrid electric vehicle’s electrical components. Its placement is critical, as it can affect airflow and thermal performance of other heat exchangers, including the condenser for the air conditioning system, thereby influencing overall vehicle comfort and energy consumption.

In this study, I based the hybrid electric vehicle development on a shared platform with a conventional fuel-powered model to minimize costs and time. The goal was to reuse as many cooling system components as possible while integrating the low-temperature radiator. The cooling module typically includes the high-temperature radiator (for engine cooling), condenser (for air conditioning), and potentially an intercooler. Adding the low-temperature radiator necessitates careful spatial arrangement to avoid detrimental effects on air conditioning performance. I evaluated two primary positions for the low-temperature radiator within the cooling module: the upper front section and the mid-lower front section. The selection process involved a virtual design workflow, utilizing one-dimensional system simulation with GT-cool software for air conditioning performance analysis and computational fluid dynamics with Star-CCM+ for airflow assessment. This integrated approach allowed for a comprehensive evaluation early in the design phase, reducing reliance on physical prototypes and accelerating development cycles for hybrid electric vehicles.

To ensure the reliability of the virtual analysis, I first established and calibrated a one-dimensional model of the air conditioning system against bench test data. The model components, as shown in the simulation layout, include the compressor, condenser, expansion valve, evaporator, and connecting pipelines, representing a typical refrigeration cycle. The calibration was performed under four operating conditions corresponding to vehicle speeds: idle, 50 km/h, 80 km/h, and 110 km/h, all in maximum cooling mode with recirculated air. Key parameters for these conditions are summarized in Table 1, where evaporator inlet conditions are fixed, while condenser inlet air temperature and velocity are derived from CFD analysis or estimated based on real-world scenarios for hybrid electric vehicles.

| Simulation Case | Evaporator Inlet Air Temperature (°C) | Evaporator Inlet Air Humidity (%RH) | Evaporator Airflow Rate (kg/min) | Condenser Inlet Air Temperature (°C) | Condenser Inlet Air Average Velocity (m/s) | Compressor Speed (r/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Idle) | 35 | 25 | 8 | 43 | 1.32 | 1,080 |

| 2 (50 km/h) | 35 | 25 | 8 | 43 | 1.59 | 2,150 |

| 3 (80 km/h) | 35 | 25 | 8 | 43 | 2.14 | 2,300 |

| 4 (110 km/h) | 35 | 25 | 8 | 43 | 2.76 | 3,100 |

The calibration results demonstrated good agreement between simulation and experimental data, with errors generally within ±10% for key performance indicators such as evaporator outlet air temperature, cooling capacity, and compressor discharge pressure. For instance, the evaporator outlet air temperature decreased progressively across cases in both simulation and tests, validating the model’s predictive capability for trend analysis. This calibrated model served as the foundation for evaluating the impact of low-temperature radiator placement in hybrid electric vehicles. The performance metrics are expressed through fundamental thermodynamic relationships. For example, the cooling capacity \( Q_{evap} \) of the evaporator can be calculated as:

$$ Q_{evap} = \dot{m}_{air} \cdot c_p \cdot (T_{in,evap} – T_{out,evap}) $$

where \( \dot{m}_{air} \) is the air mass flow rate, \( c_p \) is the specific heat capacity of air, and \( T_{in,evap} \) and \( T_{out,evap} \) are the evaporator inlet and outlet air temperatures, respectively. Similarly, the compressor work and system pressure ratios are influenced by condenser conditions, which are affected by the low-temperature radiator’s position in hybrid electric vehicles.

With the calibrated model, I proceeded to assess how the low-temperature radiator’s location affects condenser inlet air properties—specifically, air temperature and flow distribution—which are critical for air conditioning performance in hybrid electric vehicles. The cooling module’s front area was conceptually divided into upper, middle, and lower sections. The middle section was deemed unsuitable due to obstruction by crash beams, which would block airflow and negate the cooling function for the low-temperature radiator. Thus, I focused on the upper and lower sections. Preliminary considerations are summarized in Table 2, highlighting trade-offs between negative impacts on condenser performance, airflow requirements for the low-temperature radiator, and additional vehicle modifications.

| Position | Negative Impact on Condenser Inlet Air | Meeting Low-Temperature Radiator Airflow Demand | Measures to Ensure Cooling Module Airflow | Other Impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper Section | Relatively small | Basically satisfied | Increasing fan power, etc. | Changes to front-end support structure required |

| Middle Section | Minimal (but blocked by crash beam) | Not satisfied due to obstruction | None | Renders low-temperature radiator ineffective |

| Lower Section | Relatively large | Satisfied | None | None |

For the lower section placement, I adjusted the position upward to avoid covering the subcooling region of the condenser, as shown in the mid-lower configuration. This is important because the low-temperature radiator, operating at lower temperatures than the engine coolant, can still heat the incoming air, potentially raising the condenser inlet temperature and reducing subcooling efficiency. In hybrid electric vehicles, where air conditioning performance is crucial for passenger comfort and energy efficiency, even slight increases in condenser inlet temperature can degrade system performance. To quantify this, I defined two analysis cases based on common driving scenarios for hybrid electric vehicles: low to medium speeds (idle and 50 km/h), where electric or hybrid modes are frequently used, placing high thermal loads on the low-temperature radiator. The condenser inlet air conditions for these cases, incorporating the effect of the low-temperature radiator, are detailed in Table 3. Note that condenser inlet air velocity is maintained at levels similar to the baseline by adjusting fan performance, but temperature becomes non-uniform due to localized heating from the low-temperature radiator.

| Simulation Case | Evaporator Inlet Air Temperature (°C) | Evaporator Inlet Air Humidity (%RH) | Evaporator Airflow Rate (kg/min) | Condenser Inlet Air Temperature Range (°C) | Condenser Inlet Air Average Velocity (m/s) | Compressor Speed (r/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (Idle) | 35 | 25 | 8 | 43–52 (non-uniform) | 1.32 | 4,500 |

| 2 (50 km/h) | 35 | 25 | 8 | 43–52 (non-uniform) | 1.59 | 6,500 |

The non-uniform temperature distribution arises because air passing through the low-temperature radiator is warmed, creating hotter zones directly behind it. For the upper position, the heated area is concentrated at the top of the condenser, while for the mid-lower position, it affects the central to lower regions. This localized heating can be modeled by segmenting the condenser into zones with different inlet temperatures. In the simulation, I applied temperature profiles based on CFD results: for the upper position, temperatures range from 43°C in unobstructed areas to 52°C behind the low-temperature radiator; similarly, for the mid-lower position, the same range applies but over a different spatial extent. The impact on air conditioning performance is then evaluated through the one-dimensional model, with results compared to a baseline scenario without the low-temperature radiator.

The simulation outcomes for key air conditioning performance parameters are presented in Table 4, which consolidates data for evaporator outlet air temperature, cooling capacity, and compressor discharge pressure across the two cases and three configurations: baseline (no low-temperature radiator), low-temperature radiator in upper position, and low-temperature radiator in mid-lower position. These results highlight the subtle but important effects of the low-temperature radiator’s placement in hybrid electric vehicles.

| Configuration | Simulation Case | Evaporator Outlet Air Temperature (°C) | Evaporator Cooling Capacity (kW) | Compressor Discharge Pressure (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (No Low-Temperature Radiator) | 1 (Idle) | 10.12 | 5.42 | 1.81 |

| 2 (50 km/h) | 9.85 | 5.48 | 1.83 | |

| Low-Temperature Radiator in Upper Position | 1 (Idle) | 10.29 | 5.38 | 1.87 |

| 2 (50 km/h) | 10.02 | 5.44 | 1.90 | |

| Low-Temperature Radiator in Mid-Lower Position | 1 (Idle) | 10.32 | 5.37 | 1.88 |

| 2 (50 km/h) | 10.04 | 5.43 | 1.91 |

From Table 4, it is evident that adding a low-temperature radiator in front of the condenser, regardless of position, leads to a slight degradation in air conditioning performance for hybrid electric vehicles. Compared to the baseline, the evaporator outlet air temperature increases by approximately 0.03°C to 0.17°C, while cooling capacity decreases by 0.02 kW to 0.04 kW. These changes are minimal; for instance, a temperature rise of less than 0.5°C is likely imperceptible to passengers, as air further warms through ducts and HVAC components. The compressor discharge pressure rises by about 60 kPa to 90 kPa, reaching up to 1.90 MPa, which remains within safe operational limits for typical automotive air conditioning systems. The performance difference between the upper and mid-lower positions is marginal, with the upper position showing slightly better results (e.g., 0.03°C lower evaporator outlet temperature in Case 1). This can be attributed to the upper placement causing less obstruction to the condenser’s core airflow paths, as expressed by the heat transfer equation for the condenser:

$$ Q_{cond} = U \cdot A \cdot \Delta T_{lm} $$

where \( Q_{cond} \) is the heat rejection rate, \( U \) is the overall heat transfer coefficient, \( A \) is the surface area, and \( \Delta T_{lm} \) is the log-mean temperature difference. The low-temperature radiator’s position affects \( \Delta T_{lm} \) by altering the inlet air temperature distribution, thereby influencing \( Q_{cond} \) and subsequently the refrigeration cycle efficiency in hybrid electric vehicles.

However, performance alone is not the sole criterion for selecting the low-temperature radiator position in hybrid electric vehicles. I also considered practical aspects such as development cost, schedule, and implementation difficulty. As indicated in Table 2, placing the low-temperature radiator in the upper section would require modifications to the front-end support structure, adding complexity and cost to vehicle integration. In contrast, the mid-lower position avoids such changes, as it fits within existing packaging constraints without major structural revisions. Additionally, the mid-lower position adequately meets the airflow demand for the low-temperature radiator itself, ensuring effective cooling of hybrid electric vehicle components like power electronics and motors. Given that the performance penalty of the mid-lower position is negligible (differences under 0.05°C in temperature and 0.01 kW in cooling capacity), it represents a balanced solution for hybrid electric vehicle development.

Based on this analysis, I conclude that for this hybrid electric vehicle platform, positioning the low-temperature radiator at the front of the cooling module in the mid-lower section is the optimal choice. This layout minimizes negative impacts on air conditioning refrigeration performance while avoiding costly vehicle modifications, aligning with the goals of reduced development time and cost. It is worth noting that the virtual design process employed here—integrating one-dimensional system simulation, computational fluid dynamics, and experimental calibration—proved invaluable for making informed decisions early in the design phase. This approach not only applies to air conditioning systems but can be extended to other vehicle subsystems, enhancing the overall integration process for hybrid electric vehicles.

In summary, the design of cooling modules for hybrid electric vehicles requires careful consideration of thermal management interactions, particularly when adding a low-temperature radiator. Through a methodical virtual analysis, I evaluated how different placements affect air conditioning performance, using calibrated models and realistic operating conditions. The results show that while any front-mounted low-temperature radiator slightly degrades cooling performance, the mid-lower position offers a practical compromise for hybrid electric vehicles. This work underscores the importance of a holistic, simulation-driven approach in automotive engineering, enabling efficient development of complex systems like those in hybrid electric vehicles. Future studies could explore advanced materials, active airflow control, or optimized heat exchanger geometries to further mitigate performance trade-offs in hybrid electric vehicles.