As we delve into the evolving landscape of energy storage, solid state batteries emerge as a pivotal innovation poised to redefine the future of electric vehicles and renewable energy systems. These batteries, which replace conventional liquid electrolytes with solid alternatives, offer enhanced safety, higher energy density, and improved longevity. In this comprehensive analysis, we explore the current state of solid state battery technology, global industry trends, and the multifaceted challenges hindering widespread adoption. Our focus is on providing an in-depth perspective, supported by data, tables, and mathematical models, to illuminate the path forward for solid state batteries. We will repeatedly emphasize the significance of solid state battery advancements, as these devices represent a transformative shift in energy storage solutions. Throughout this discussion, we aim to highlight key aspects such as material science, economic factors, and policy implications, ensuring a holistic understanding of solid state battery development.

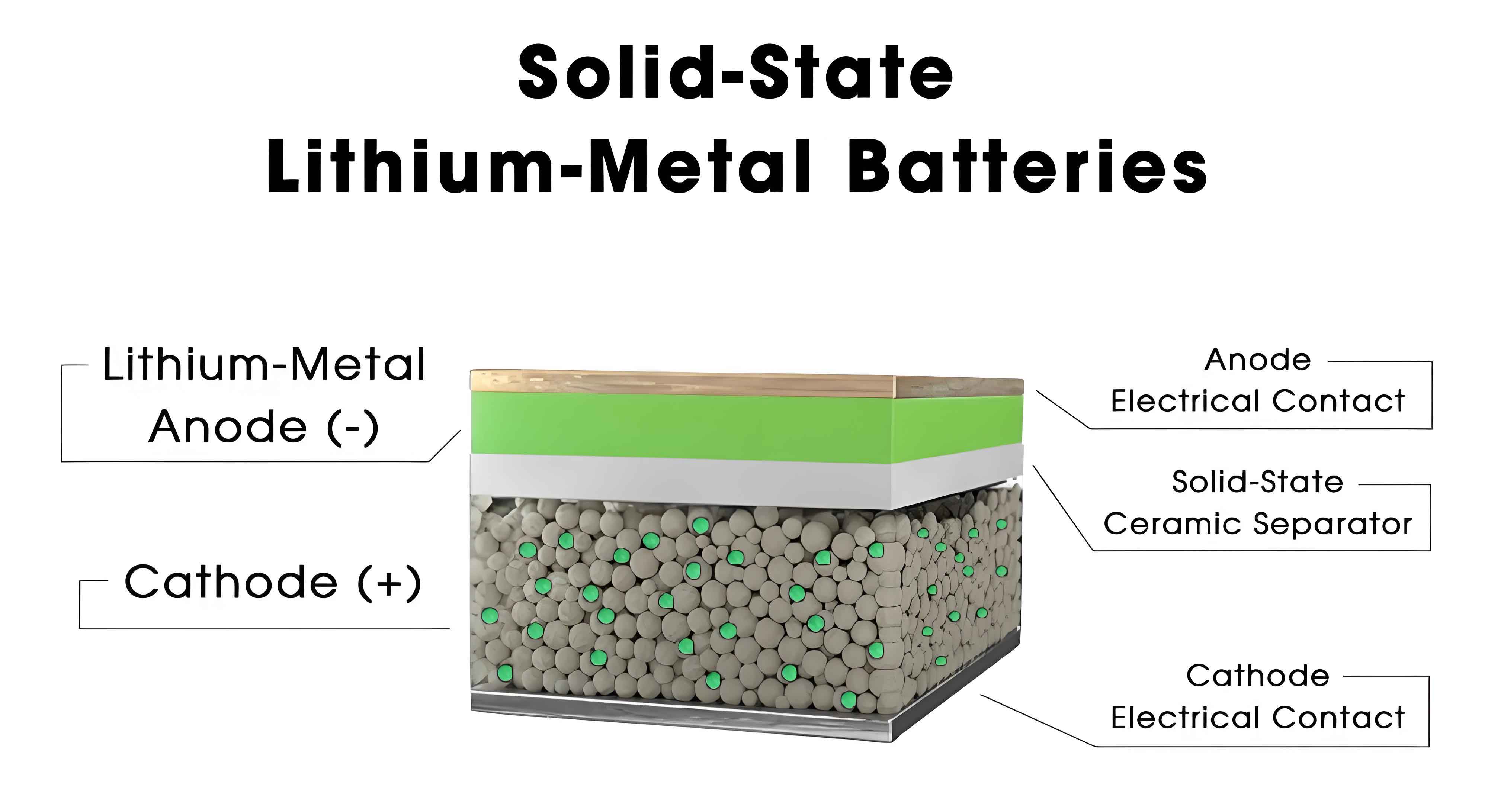

The fundamental principle behind solid state batteries revolves around the use of solid electrolytes, which can be composed of polymers, oxides, or sulfides. Unlike traditional lithium-ion batteries that rely on liquid electrolytes, solid state batteries eliminate risks of leakage and thermal runaway, thereby enhancing safety. Moreover, solid state batteries enable the use of high-capacity electrodes, such as lithium metal, which can significantly boost energy density. For instance, the theoretical energy density of a solid state battery can exceed 500 Wh/kg, compared to around 250-300 Wh/kg for conventional liquid-based systems. This improvement is crucial for applications like electric vehicles, where range and weight are critical factors. As we proceed, we will dissect the technical nuances of solid state batteries, including their electrochemical behavior and performance metrics, using equations to model key parameters. For example, the ionic conductivity of solid electrolytes, a vital property, can be described by the Arrhenius equation: $$ \sigma = \sigma_0 \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{k_B T}\right) $$ where $\sigma$ is the ionic conductivity, $\sigma_0$ is the pre-exponential factor, $E_a$ is the activation energy, $k_B$ is Boltzmann’s constant, and $T$ is the temperature in Kelvin. This equation helps us understand how temperature influences the performance of solid state batteries, particularly for polymer-based systems that exhibit low conductivity at room temperature.

To systematically evaluate the different approaches to solid state battery technology, we have compiled a detailed table comparing the three primary electrolyte types: polymer, oxide, and sulfide. This table summarizes their material compositions, ionic conductivities, advantages, disadvantages, and leading companies involved in development. As we analyze these pathways, it becomes evident that each has unique trade-offs in terms of conductivity, stability, and manufacturability. For instance, sulfide-based solid state batteries offer the highest room-temperature conductivity but face challenges with interfacial stability, while oxide-based systems are more feasible for near-term commercialization due to their balance of properties. The data in this table is derived from recent research and industry reports, reflecting the current state of solid state battery innovation. We encourage readers to refer to this table as a reference point for understanding the diverse landscape of solid state battery technologies.

| Type | Electrolyte Materials | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Advantages | Disadvantages | Key Companies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer | Polyethylene oxide (PEO), Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) | 10^{-7} to 10^{-5} at room temperature; up to 10^{-4} at elevated temperatures | Excellent flexibility, ease of processing, good interfacial compatibility | Low conductivity at room temperature, narrow electrochemical window | Bollore, Blue Solutions, Solid Energy |

| Oxide | LiPON, NASICON-type materials | 10^{-6} to 10^{-3} | High mechanical strength, thermal stability, wide electrochemical window | Poor interfacial contact, relatively lower overall conductivity | ProLogium, QuantumScape, Ganfeng Lithium, WeLion New Energy |

| Sulfide | LiGPS, LiSnPS, LiSiPS | 10^{-7} to 10^{-2} | Highest room-temperature conductivity, good deformability | Susceptible to oxidation, interfacial instability | Toyota, Samsung SDI, Panasonic, Solid Power, CATL, BYD, SVOLT |

In the global context, the development of solid state batteries is being aggressively pursued by major economies, each with distinct strategic initiatives. Japan, for example, has established a collaborative ecosystem involving automotive giants and research institutions to accelerate solid state battery innovation. The Japanese government’s investment of over 1,205 billion yen underscores its commitment to achieving commercialization by 2030. Similarly, South Korea’s “K-Battery Strategy” allocates 20 trillion won for research and development, aiming for preliminary commercialization by 2027. European nations, through the “Battery 2030+ Initiative,” have mobilized 32 billion euros to support solid state battery projects, focusing on sustainability and circular economy principles. In the United States, the “National Blueprint for Lithium Batteries” sets a clear target for demonstrating solid state battery applications by 2030, with companies like Solid Power reporting prototypes with energy densities of 390 Wh/kg. As we examine these international efforts, it is clear that solid state batteries are a focal point of technological competition, driven by the potential to overcome limitations of current lithium-ion systems.

Turning to the domestic landscape, China has made significant strides in solid state battery technology, leveraging its robust battery manufacturing infrastructure. Government policies, such as the “New Energy Vehicle Industry High-Quality Development Action Plan,” emphasize innovation in solid state batteries, with funding allocated through national research programs. Notably, semi-solid state batteries have already been deployed in vehicles like the Nio ET7 and IM L6, achieving energy densities of 360 Wh/kg and ranges exceeding 1,000 km. However, despite these advancements, China faces unique challenges, including patent constraints dominated by Japanese and Korean firms, and an underdeveloped standard system for solid state batteries. Furthermore, the transition to solid state batteries could disrupt China’s established liquid battery industry, which accounts for over 70% of global production in key materials like anodes and electrolytes. As we reflect on these issues, we must consider how to navigate this transition while maintaining leadership in the broader energy storage sector.

One of the core technical hurdles in solid state battery development is the interface between electrodes and solid electrolytes. The high interfacial impedance can lead to poor rate capability and reduced cycle life. To quantify this, we can model the interfacial resistance using the equation: $$ R_{int} = \frac{\delta}{\sigma_{eff}} $$ where $R_{int}$ is the interfacial resistance, $\delta$ is the thickness of the interfacial layer, and $\sigma_{eff}$ is the effective conductivity. This resistance often results from poor physical contact and chemical incompatibility, necessitating strategies like nanostructuring or the use of composite electrolytes. For example, incorporating a thin layer of liquid electrolyte in semi-solid state batteries can mitigate this issue, but it compromises the safety advantages of all-solid state systems. Additionally, the growth of lithium dendrites in metal anodes poses a significant safety risk, which can be described by the Sand’s time equation for dendrite initiation: $$ t_s = \frac{\pi D n F C_0}{4 J^2} $$ where $t_s$ is the Sand’s time, $D$ is the diffusion coefficient, $n$ is the number of electrons, $F$ is Faraday’s constant, $C_0$ is the initial concentration, and $J$ is the current density. Addressing these challenges requires interdisciplinary research in materials science and electrochemistry, as we strive to enhance the performance and reliability of solid state batteries.

Cost considerations are equally critical in the commercialization of solid state batteries. Currently, the production cost for all-solid state batteries ranges from 1.5 to 2.5 yuan/Wh, significantly higher than the 0.5 to 1.0 yuan/Wh for liquid lithium-ion batteries. This cost disparity stems from several factors, including expensive raw materials for solid electrolytes and immature manufacturing processes. To illustrate, we can break down the cost components using a simple model: $$ C_{total} = C_{material} + C_{manufacturing} + C_{R&D} $$ where $C_{total}$ is the total cost, $C_{material}$ is the material cost, $C_{manufacturing}$ is the manufacturing cost, and $C_{R&D}$ is the research and development cost. For solid state batteries, $C_{material}$ is dominated by solid electrolytes and specialized electrodes, while $C_{manufacturing}$ includes costs for custom equipment like dry room facilities and precision coating machines. As production scales up, economies of scale could reduce these costs, but initial investments remain high. We estimate that achieving cost parity with liquid batteries will require a combination of technological breakthroughs and policy support, such as subsidies or tax incentives for solid state battery production.

In terms of policy recommendations, we propose a multi-faceted approach to accelerate the development of solid state batteries. First, strengthening national coordination through strategic planning can optimize产业链布局 and resource allocation. This includes establishing innovation platforms that bring together academia, industry, and government to tackle key technical challenges. Second, increasing financial support via tax credits, grants, and venture capital can mitigate the high costs associated with solid state battery R&D. For instance, offering tax exemptions for companies that achieve specific energy density or safety milestones could spur innovation. Third, accelerating standard-setting processes is essential for ensuring product quality and facilitating international trade. By participating in global standard organizations, stakeholders can promote the adoption of unified testing methods and safety protocols for solid state batteries. These measures, combined with a focus on intellectual property management, can help build a resilient and competitive solid state battery industry.

To further elucidate the performance characteristics of solid state batteries, we present a table summarizing key metrics compared to conventional lithium-ion batteries. This comparison highlights the potential advantages of solid state batteries in terms of energy density, safety, and cycle life, while also acknowledging current limitations in conductivity and cost. As research progresses, we anticipate improvements in these areas, driven by advancements in material science and manufacturing techniques. For example, the development of hybrid electrolytes that combine the benefits of different solid state battery types could lead to optimized performance. We encourage ongoing monitoring of these metrics to track the evolution of solid state battery technology and its impact on various applications.

| Parameter | Solid State Batteries | Conventional Lithium-Ion Batteries |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Density (Wh/kg) | 300-500 (theoretical up to 700) | 150-300 |

| Safety | High (resistant to leakage and thermal runaway) | Moderate (risk of fire and explosion) |

| Cycle Life (cycles) | 1,000-2,000+ (depending on technology) | 500-1,500 |

| Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | 10^{-7} to 10^{-2} (varies by electrolyte) | 10^{-2} to 10^{-1} (for liquid electrolytes) |

| Cost (yuan/Wh) | 1.5-2.5 (current estimate) | 0.5-1.0 |

Another critical aspect of solid state batteries is their environmental impact and sustainability. The use of solid electrolytes can reduce the reliance on volatile organic solvents, lowering the carbon footprint of battery production. Moreover, solid state batteries are more amenable to recycling due to their stable solid components, which can be separated and reused. We can model the lifecycle environmental benefits using equations like the greenhouse gas emissions reduction: $$ \Delta GHG = E_{savings} \times EF_{grid} $$ where $\Delta GHG$ is the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, $E_{savings}$ is the energy savings from using solid state batteries, and $EF_{grid}$ is the emission factor of the grid. By integrating solid state batteries into renewable energy systems, we can enhance grid stability and support the transition to a low-carbon economy. As we advance, it is imperative to conduct lifecycle assessments to quantify these benefits and guide policy decisions.

In conclusion, the journey toward widespread adoption of solid state batteries is fraught with challenges but brimming with potential. From technical hurdles like low ionic conductivity and interfacial issues to economic barriers such as high costs and patent constraints, the path forward requires concerted efforts across multiple domains. However, the promise of safer, higher-energy-density batteries makes this pursuit worthwhile. We believe that through collaborative research, strategic policy interventions, and international cooperation, the solid state battery industry can overcome these obstacles and unlock new possibilities for energy storage. As we continue to monitor developments in solid state battery technology, we remain optimistic about its role in shaping a sustainable and electrified future. The repeated emphasis on solid state batteries throughout this discussion underscores their transformative potential, and we urge stakeholders to prioritize investments and innovations in this critical field.