As a diagnostic technician specializing in modern powertrains, I consistently find that the most compelling challenges arise from the intricate dance of systems within a hybrid electric vehicle. The complexity isn’t just in the number of components but in the profound interconnectedness where a fault in one subsystem can manifest as a warning in another, seemingly unrelated, module. This narrative details a recent, illuminating case that underscores this principle and highlights the critical importance of foundational maintenance in advanced propulsion systems.

The vehicle in question was a luxury SUV, a prime example of a sophisticated hybrid electric vehicle. The client’s concern was straightforward: while driving, the dedicated hybrid system warning lamp and the vehicle stability control (anti-skid) indicator illuminated simultaneously on the instrument cluster. This pairing of warnings is always a red flag, signaling that the vehicle’s core control systems are in a compromised state, often invoking a fail-safe or reduced-power mode to protect both the hardware and the occupants.

Initial verification confirmed the fault. Connecting the dedicated diagnostic scan tool revealed a telling duo of stored codes. The Hybrid Powertrain Control Module (HPCM) held a code P3125, defined as “Electric Coolant Pump System.” Simultaneously, the Anti-lock Braking System (ABS) module stored a code C1130, meaning “Engine Signal 1.” Consulting the service information immediately clarified the hierarchy: C1130 was a consequential code, stored because the HPCM had reported a fault that affected data shared on the vehicle’s high-speed CAN network. Therefore, the root cause investigation had to focus squarely on the P3125 code related to the electric coolant pump. The diagnostic tree for this code, as per manufacturer guidelines, is summarized below.

| Diagnostic Trouble Code | Module | Set Condition | Potential Root Causes |

|---|---|---|---|

| P3125 | Hybrid Powertrain Control Module (HPCM) | The HPCM calculates the feedback duty cycle from the electric coolant pump to be between 83% and 91% for a continuous period exceeding 30 seconds. | 1. Open or short circuit in the pump control/sense wiring. 2. Faulty electric coolant pump assembly. 3. Issues with system voltage supply or ground. |

The freeze frame data associated with the fault was the first critical clue. The parameter labeled “Inverter Pump Monitor” was captured at 89.2%. In a healthy system for this hybrid electric vehicle, the control module expects this value to be below 83% during normal operation. This value is typically a calculated duty cycle or a speed feedback signal from the pump. A value hovering near 90% indicates the control module is commanding near-maximum effort from the pump, but the feedback suggests the pump is not achieving the expected performance, leading to a fault flag. After clearing the codes, I performed an active test of the pump. The monitor value now fluctuated normally between 74% and 78.2%. Furthermore, with the vehicle placed in a ready state and the system transitioning to EV mode, an audible hum from the front of the vehicle confirmed the electric coolant pump was operational. The fault was clearly intermittent.

Intermittent faults in a hybrid electric vehicle are particularly vexing. They point away from a complete hard failure and towards issues like high-resistance connections, thermal sensitivity, or—as would become crucial—system performance being hindered by external factors. The electrical circuit for the pump is a classic example of a smart motor driver. The HPCM sends a Pulse-Width Modulated (PWM) control signal to dictate pump speed, while simultaneously monitoring a feedback signal from the pump. The relationship between commanded effort and actual performance can be modeled. If we consider the pump’s effective operational speed (ω_actual) against the commanded signal duty cycle (D_cmd), a fault condition arises when the ratio deviates beyond a calibrated threshold (γ).

$$ \text{Fault Condition: } \left| \frac{\omega_{\text{actual}}}{\omega_{\text{expected}}(D_{\text{cmd}})} – 1 \right| > \gamma $$

where $\omega_{\text{expected}}(D_{\text{cmd}})$ is the expected speed as a function of the command duty cycle, and $\gamma$ is the tolerance, often around 0.08 (or 8%) for such systems.

A thorough wiring inspection was mandatory. The circuit diagram showed a four-wire connection: power, ground, control, and feedback. Disconnecting the pump connector and measuring voltage between the power and ground terminals with ignition on revealed full system voltage, eliminating concerns about primary supply. Continuity checks between the HPCM and pump connectors for both the control and feedback lines showed resistances below 1 ohm. Insulation checks for short circuits to power or ground were also negative. The electrical integrity of the circuit was confirmed. The evidence was beginning to point towards the pump itself as the culprit, perhaps an internal brushless motor driver failing under load or a bearing creating intermittent drag.

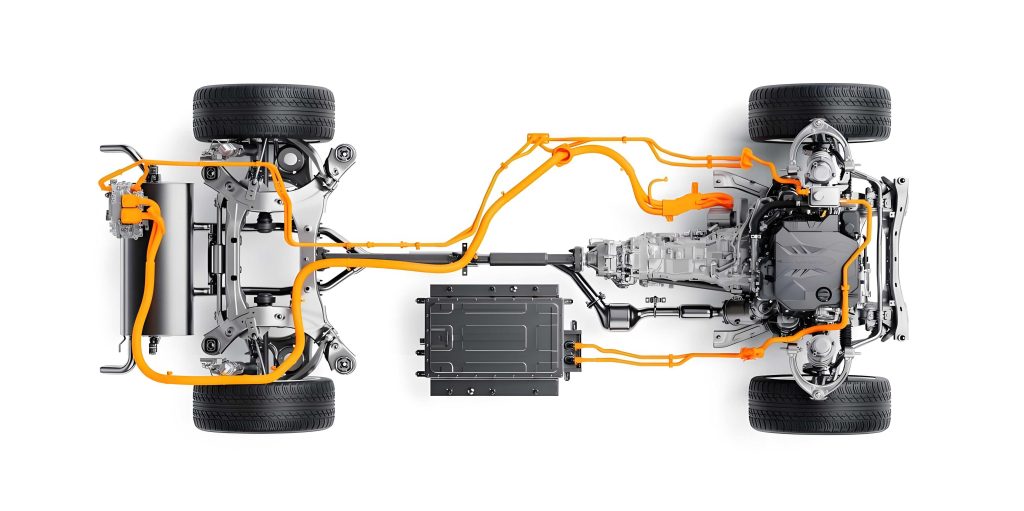

However, before condemning the expensive pump assembly, a fundamental physical check was necessary. In any hybrid electric vehicle, the high-voltage components—the traction motor, inverter, and often the DC-DC converter—generate significant waste heat. They are cooled by a dedicated, sealed high-voltage cooling loop, separate from the engine cooling system. This loop is critical for preventing thermal runaway and ensuring the longevity of expensive power electronics. The heart of this loop is the electric coolant pump. If this loop is under-filled or contains air pockets, the pump can cavitate. Cavitation occurs when the pump tries to move fluid but encounters vapor bubbles, leading to a drastic drop in pumping efficiency and flow rate. The pump motor then works harder (drawing more current, potentially reflected in a higher feedback signal) to overcome this, but the actual coolant flow is insufficient.

The physics of cavitation is relevant here. The Net Positive Suction Head Available (NPSH_A) must exceed the Net Positive Suction Head Required (NPSH_R) by the pump. When coolant level is low or air is present, NPSH_A drops. Cavitation onset can be approximated when:

$$ \text{NPSH}_A \approx \frac{P_{\text{inlet}} – P_{\text{vapor}}}{\rho g} < \text{NPSH}_R $$

where $P_{\text{inlet}}$ is the pressure at the pump inlet, $P_{\text{vapor}}$ is the vapor pressure of the coolant, $\rho$ is coolant density, and $g$ is gravity. Low coolant level reduces $P_{\text{inlet}}$, precipitating cavitation.

Upon opening the dedicated coolant reservoir for the hybrid electric vehicle’s high-voltage cooling system, the root cause became glaringly apparent: the coolant level was critically low, well below the minimum cold-fill mark. This discovery immediately re-framed the entire diagnosis. The intermittent high feedback signal was not due to a faulty pump but to the pump struggling against a fluid-starved system, likely with a significant air pocket. The pump would occasionally “catch” and move some fluid, explaining the intermittent nature, but under sustained demand (like during extended EV mode driving), its performance would degrade, triggering the fault. Air in the system also has a compressibility factor that severely impacts the pump’s hydraulic performance, a relationship absent in a pure liquid system.

This finding led to a crucial conversation with the owner. It was revealed the hybrid electric vehicle had undergone significant front-end repair work at a non-specialist facility after a collision some months prior. It was highly probable that the high-voltage cooling loop had been opened for radiator or component replacement but had not been correctly refilled and, more importantly, bled of air during the repair process. Over time, the low coolant level led to the intermittent fault.

The repair procedure for such an issue in a hybrid electric vehicle is specific. Simply adding coolant to the reservoir is insufficient. The system must be actively bled to remove trapped air. The prescribed method often involves using the diagnostic tool to activate the electric coolant pump independently of other systems, or by putting the vehicle through specific drive cycles that activate the pump at varying speeds, all while the reservoir cap is off and the system is topped up. The process continues until no more air bubbles are visible entering the reservoir. For this vehicle, with the system in READY mode (engine off, hybrid system active), the electric pump was cycled. After several minutes of operation and careful topping up, the bubble flow ceased, indicating a purged system.

| Observed Symptom / Data | If Root Cause is Electrical Pump Fault | If Root Cause is Low Coolant / Air in System | Finding in This Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermittent “Inverter Pump Monitor” value ~89% | Likely consistent when fault is active; pump feedback circuit may show instability. | Intermittent; correlates with pump load and fluid conditions. May be normal during active test with no load. | Intermittent high reading; normal during active test. |

| Audible pump operation | May be noisy, irregular, or silent. | Sound may be normal, or include gurgling/cavitation noises. | Normal audible operation present. |

| Circuit checks (voltage, continuity) | Typically normal, unless an internal motor fault affects circuit. | Entirely normal. | All measurements within specification. |

| Physical inspection of cooling system | Coolant level normal; no leaks. | Coolant level low; possible signs of air ingress or past leakage. | Coolant level critically low. |

| Correlation with recent service history | May be unrelated. | Often follows repairs involving the cooling circuit. | Correlated with prior front-end collision repair. |

The resolution was elegantly simple yet profoundly important. After replenishing the coolant to the specified level with the correct hybrid-specific coolant mixture and executing a proper bleeding procedure, the vehicle was test-driven extensively. The hybrid electric vehicle operated flawlessly. All fault codes remained cleared, and the “Inverter Pump Monitor” data stream now showed stable values between 72% and 80% under all operating conditions, including aggressive acceleration that demanded maximum inverter cooling. The secondary ABS code (C1130) never reappeared, confirming its dependent nature.

This case serves as a powerful object lesson in diagnosing complex systems. The journey from two seemingly severe warning lights to a simple low coolant condition underscores several key principles for working on any hybrid electric vehicle, or indeed any modern vehicle with interconnected control networks.

First, understand the system hierarchy and data flow. Modern vehicles are networks of Electronic Control Units (ECUs). A fault in a primary module like the HPCM will often cause symptom codes in subordinate or peer modules (like the ABS) that rely on its data. Diagnosing the consequential code first is a path to confusion. The primary code must always be addressed. This network dependency can be expressed as a data dependency matrix. If ECU A provides signal X to ECUs B and C, a failure in A that corrupts X will likely cause plausibility faults in B and C.

Second, always corroborate live data with physical inspection. The scan tool is indispensable, but it interprets the world through sensors and algorithms. The freeze frame data indicated a pump performance issue. The electrical tests ruled out wiring. The logical next step was to replace the pump. However, a basic physical check—looking at the coolant reservoir—revealed the true environmental condition causing the performance issue. This step is often overlooked in the rush to trust electronic diagnostics. The fundamental laws of physics still govern electromechanical systems. The power (P) required to drive a centrifugal pump is related to the flow rate (Q), pressure head (H), density (ρ), and efficiency (η):

$$ P = \frac{\rho g H Q}{\eta} $$

If air entrainment reduces the effective density (ρ) or the pump operates inefficiently (low η) due to cavitation, the power draw and operational characteristics change, which the control module interprets as a fault.

Third, consider the history of the hybrid electric vehicle. Repair history is not just administrative data; it is a diagnostic clue. A recent accident repair involving the front structure should immediately raise suspicion for cooling system integrity, sensor alignment, and proper bleeding procedures for all fluid loops, especially the sensitive high-voltage cooling system.

Fourth, appreciate the unique demands of a hybrid electric vehicle’s thermal management system. Unlike a conventional vehicle where the engine’s water pump is mechanically driven and coolant flow is roughly proportional to engine speed, the hybrid electric vehicle’s power electronics cooling is demand-based and electrically driven. The pump must respond instantly to thermal loads from the inverter during high-torque electric motor operation, even if the gasoline engine is off. This system is more sensitive to air pockets and low coolant levels because its duty cycle is more variable and critical. A table comparing conventional and hybrid electric vehicle cooling system characteristics is informative.

| Characteristic | Conventional Vehicle (Engine Cooling) | Hybrid Electric Vehicle (HV Power Electronics Cooling) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Heat Source | Internal Combustion Engine | Inverter, Traction Motor, DC-DC Converter |

| Pump Drive Method | Mechanical (belt-driven from engine) | Electric (brushless DC motor controlled by HPCM) |

| Coolant Flow Correlation | Directly tied to engine RPM | Demand-based, independent of engine state; can run with engine off. |

| Typical Operating Temperature | ~90-105°C (thermostat regulated) | ~60-70°C (lower for semiconductor efficiency) |

| Fault Sensitivity to Low Coolant | May cause overheating; gradual symptom onset. | Can cause immediate performance derating, fault codes, and pump cavitation due to precise flow expectations. |

| System Pressure | Moderate (capped radiator pressure) | Sealed, often maintained at a specific pressure range for boiling point elevation and air expulsion. |

Finally, this case reinforces the concept of system interdependence. The hybrid fault lamp illuminated due to a cooling system fault. The stability control lamp illuminated because the ABS module lost a valid data signal from the HPCM, which was busy dealing with its primary fault. This created a multi-warning light scenario that appeared far more serious to the driver than the underlying issue. Educating clients about this interdependence—that one physical problem can trigger multiple warnings—is part of modern vehicle service.

In conclusion, the diagnostic journey for this hybrid electric vehicle, from perplexing electrical fault codes to a simple fluid level correction, was a profound reminder. Advanced diagnostics on a hybrid electric vehicle require a dual-minded approach: one must be an expert in reading the digital story told by networks and modules, while simultaneously remaining a master of the physical, mechanical world where fluid dynamics, thermal transfer, and fundamental chemistry still reign supreme. The fusion of these disciplines is what defines successful troubleshooting in the age of the hybrid electric vehicle and the broader electric vehicle transition. Every fault code is a story, and the plot often hinges on the most basic elements. The key is to listen to all the characters in that story—the HPCM, the ABS module, the electric coolant pump’s feedback signal, and the silent testimony of an under-filled coolant reservoir.

To further generalize the learning, we can model the diagnostic confidence (C_d) as a function of electrical verification (E_v), physical inspection (P_i), historical data (H_d), and system knowledge (S_k). An optimal diagnosis requires all factors:

$$ C_d = \alpha \cdot E_v + \beta \cdot P_i + \gamma \cdot H_d + \delta \cdot S_k $$

where $\alpha, \beta, \gamma, \delta$ are weighting factors specific to the fault domain, and for a hybrid electric vehicle cooling fault, $\beta$ (physical inspection) might be disproportionately high relative to simpler electrical faults. Ignoring any one factor, as nearly happened when proceeding to pump replacement, increases the risk of a misdiagnosis and unnecessary repair.

This experience has solidified my protocol for any hybrid electric vehicle presenting with thermal management or powertrain codes: scan, document, analyze data, but then immediately move to a thorough visual and physical inspection of all related fluid systems, connections, and the recent service history. It is a lesson in humility and thoroughness that applies to every complex system we encounter, ensuring that the sophisticated hybrid electric vehicle remains a reliable and efficient mode of transportation.