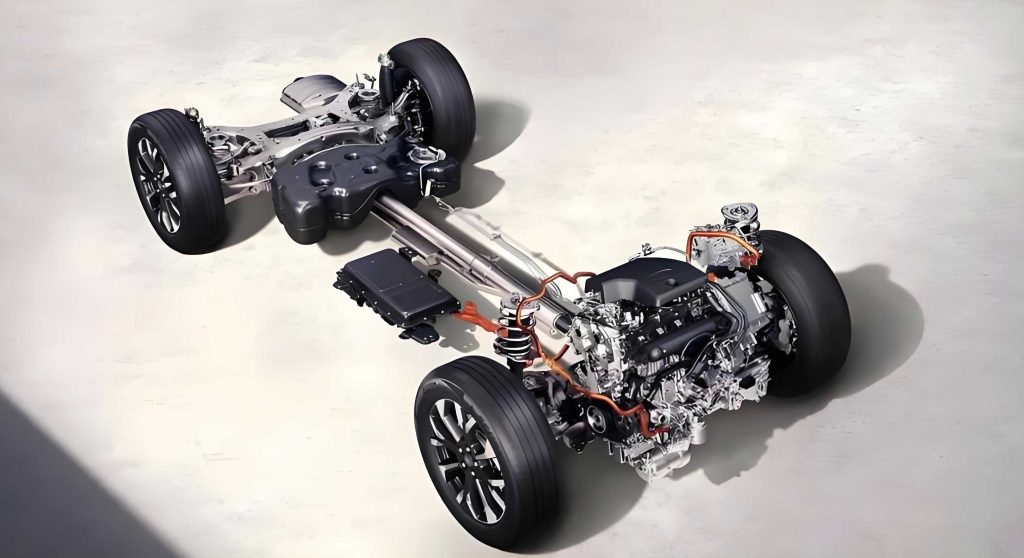

As a seasoned automotive technician specializing in electrified powertrains, I have encountered numerous complex fault scenarios in hybrid electric vehicles. The integration of high-voltage systems with traditional automotive components presents unique diagnostic challenges. In this detailed account, I will share my first-hand experience and methodology for troubleshooting critical systems, focusing on the climate control and electrical networks that are paramount to vehicle performance and safety. The proliferation of hybrid electric vehicle technology necessitates a deep understanding of both high-voltage and low-voltage interdependencies.

The core of a hybrid electric vehicle’s comfort system is the High-Voltage (HV) HVAC system. Unlike conventional vehicles, the air conditioning compressor is often an electrically-driven unit powered directly by the traction battery. This design allows for cabin cooling and battery thermal management regardless of internal combustion engine operation. The governing equation for the compressor’s power draw can be expressed as:

$$P_{comp} = V_{HV} \times I_{comp} \times \eta_{inv} \times \eta_{motor}$$

Where \(P_{comp}\) is the mechanical power output of the compressor, \(V_{HV}\) is the high-voltage bus potential (typically between 200V and 450V in a hybrid electric vehicle), \(I_{comp}\) is the current supplied, and \(\eta_{inv}\) and \(\eta_{motor}\) are the efficiencies of the inverter and motor respectively. A failure in this circuit leads directly to a loss of cooling capacity.

My diagnostic approach always begins with verifying the customer complaint and then performing a thorough scan of all relevant control modules. In the case of a hybrid electric vehicle, this includes the Powertrain Control Module (PCM), Battery Management System (BMS), and the dedicated HVAC Controller. Stored fault codes provide the initial vector for investigation. Common fault code categories in a hybrid electric vehicle HVAC system are summarized below:

| Fault Code | Module | Likely Meaning | Primary System Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| P06A000 | HVAC Controller | Electrical Fault in Refrigerant Compressor Actuation | High-Voltage Compressor Circuit |

| P142800 | Battery Management | Insulation Fault in High-Voltage Onboard Electrical System | Vehicle HV Isolation |

| P0651 | Powertrain Control | Sensor Reference Voltage “B” Malfunction | 5V Sensor Supply Circuit |

| P2127 | Powertrain Control | Accelerator Pedal Position Sensor “B” Circuit Low Voltage | Sensor Network |

Upon confirming a no-cool complaint in a hybrid electric vehicle, I first ensure the high-voltage system is operational by checking if the vehicle can propel in EV mode. Success here rules out a complete HV system shutdown. The next step is to interrogate the HVAC controller’s live data. Critical parameters to monitor include:

- Requested compressor status (On/Off)

- Measured high-voltage at the compressor terminals

- Compressor speed command and feedback

- Refrigerant pressure sensor readings

In a recent case involving a luxury hybrid electric vehicle, the data stream showed a compressor request was present, but the measured HV supply at the compressor was only 2V, far below the normal operating range of 240V to 430V. This discrepancy immediately points to a fault in the high-voltage distribution path. The equivalent circuit for diagnosing this can be modeled using Kirchhoff’s voltage law. For a simple circuit with a fuse, wiring, and load (compressor), the voltage at the load \(V_{load}\) is given by:

$$V_{load} = V_{source} – (I \times R_{wiring})$$

However, if the current \(I\) is zero due to an open circuit (blown fuse), then \(V_{load}\) will measure as a residual voltage or zero, depending on the measurement point. To systematically locate the fault, I perform a continuity and resistance check on both the low-voltage control circuit and the high-voltage power circuit, following strict safety protocols for a hybrid electric vehicle.

The low-voltage control circuit typically involves a 12V signal from the HVAC controller to the compressor’s inverter. Resistance should be minimal. For the high-voltage circuit, after safely depowering the hybrid electric vehicle system and verifying the absence of HV, I measure resistance across key points. The expected resistance for a healthy cable and fuse assembly is near zero ohms. The relationship defining a short circuit condition that would blow a fuse is based on Joule’s law of heating:

$$Q = I^2 \times R_{fuse} \times t$$

Where \(Q\) is the heat energy generated, \(I\) is the fault current, \(R_{fuse}\) is the inherent resistance of the fuse, and \(t\) is the time. When \(Q\) exceeds the fuse’s rating, it melts. Discovering an open circuit (infinite resistance) across a high-current fuse, such as a 60A unit, confirms it has blown. The subsequent investigation must determine the root cause: was it an internal compressor fault or a short in the wiring?

Further testing involves measuring insulation resistance. In a hybrid electric vehicle, the isolation resistance between the HV+ and chassis ground, and HV- and chassis ground, must be exceptionally high—typically in the megaohm range. A standard test can be expressed by rearranging Ohm’s law:

$$R_{insulation} = \frac{V_{test}}{I_{leakage}}$$

A low \(R_{insulation}\) indicates a breakdown, often due to moisture ingress or physical damage. In the mentioned case, disassembling the electric compressor revealed severe internal corrosion and water ingress. This created a low-resistance path between the HV+ and HV- terminals inside the compressor housing, leading to a catastrophic short circuit. The sequence of events is summarized in the following failure mode analysis table:

| Step | Component | Fault Condition | Resultant Effect | Mathematical Relation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Compressor Seal | Failed, allowing water ingress | Internal contamination and corrosion | Moisture concentration \(C_{H2O} \rightarrow \infty\) locally |

| 2 | Compressor HV Terminals | Bridging by conductive corrosion | Low impedance path between terminals | \(R_{short} \rightarrow 0 \Omega\) |

| 3 | High-Current Fuse | Exceeds thermal capacity | Fuse element melts (opens circuit) | \( \int I_{fault}^2 \cdot dt > K \cdot I_{rated}^2 \cdot t\) |

| 4 | HVAC System | Loss of HV power to compressor | No refrigerant compression | \(P_{comp} = 0\), Cooling capacity = 0 |

| 5 | BMS | Detects insulation fault during prior short | Stores historical insulation DTCs | \(R_{iso} < R_{threshold}\) momentarily |

The second common issue in a hybrid electric vehicle involves multiple, seemingly unrelated fault codes illuminating the dashboard. This often stems from a failure in a shared resource, such as a common sensor reference voltage supply. In a typical hybrid electric vehicle powertrain control module, a single 5V reference regulator circuit supplies multiple sensors. The equivalent electrical model is a voltage source \(V_{ref}\) with a source impedance \(Z_{source}\), powering \(n\) sensor loads with individual impedances \(Z_{load_i}\). The voltage at any sensor \(V_{sens}\) is:

$$V_{sens} = V_{ref} – I_{total} \times Z_{source}$$

$$P_{fault} = \frac{V_{ref}^2}{R_{internal\_short}}$$

This often leads to component overheating and permanent damage. Therefore, in a hybrid electric vehicle, a systematic check of all sensors on a common reference bus is essential when multiple low-voltage codes appear. The interdependencies in a hybrid electric vehicle are more complex due to the additional sensors monitoring the high-voltage battery, DC-DC converter, and electric motor phases.

Preventive maintenance for a hybrid electric vehicle’s HVAC and electrical systems cannot be overstated. I recommend a periodic inspection schedule that includes visual checks of high-voltage cable routing and connectors for integrity, measuring HV insulation resistance during major services, and ensuring drain channels for critical components like the electric compressor are clear. The condensation management around the compressor is vital; a blocked drain can lead to the exact water ingress fault described. The probability of such a fault occurring over time \(t\) can be modeled with a basic reliability function, but it is heavily influenced by environmental factors \(E\) and maintenance intervals \(T_m\):

$$R(t) = e^{-\lambda(E, T_m) \cdot t}$$

Where \(\lambda\) is the failure rate, which decreases with more frequent inspections and proper sealing checks. For the shared 5V reference circuits, a proactive measure is to monitor the quiescent current draw of the sensor network during diagnostics; a rising baseline current can indicate a sensor beginning to degrade before it fails completely and takes down the entire network.

In conclusion, diagnosing faults in a hybrid electric vehicle requires a methodical approach that respects the interplay between high-voltage power systems and low-voltage control networks. The use of live data, systematic electrical measurements, and an understanding of shared resource architectures are key. Whether addressing a lack of cooling from a failed HV compressor or unraveling a web of low-voltage sensor codes, the principles of electrical circuit analysis remain foundational. The growing sophistication of the hybrid electric vehicle platform demands that technicians continuously update their skills in both traditional automotive systems and high-voltage electrical engineering concepts. By employing detailed data logging, rigorous resistance and insulation testing, and logical fault tree analysis, even the most perplexing issues in a hybrid electric vehicle can be resolved efficiently and safely, ensuring these advanced vehicles remain reliable and comfortable for their owners.