As a researcher focused on advancing energy storage technologies, I believe that the development of all-solid-state batteries represents a pivotal step toward achieving safer and higher-energy-density power sources. The transition from conventional lithium-ion batteries to solid state batteries is driven by the need to overcome inherent safety risks associated with flammable liquid electrolytes and to push beyond the energy density limits of current systems. In this article, I will explore the challenges of single-component solid electrolytes and propose a novel composite approach, termed SHOP-type electrolytes, which integrates sulfides (S), halides (H), oxides (O), and polymers (P) to address the multifaceted requirements of commercial applications. Solid state batteries hold immense promise for electric vehicles and grid storage, but their widespread adoption hinges on the availability of solid electrolytes that balance high ionic conductivity, cost-effectiveness, stability, and processability.

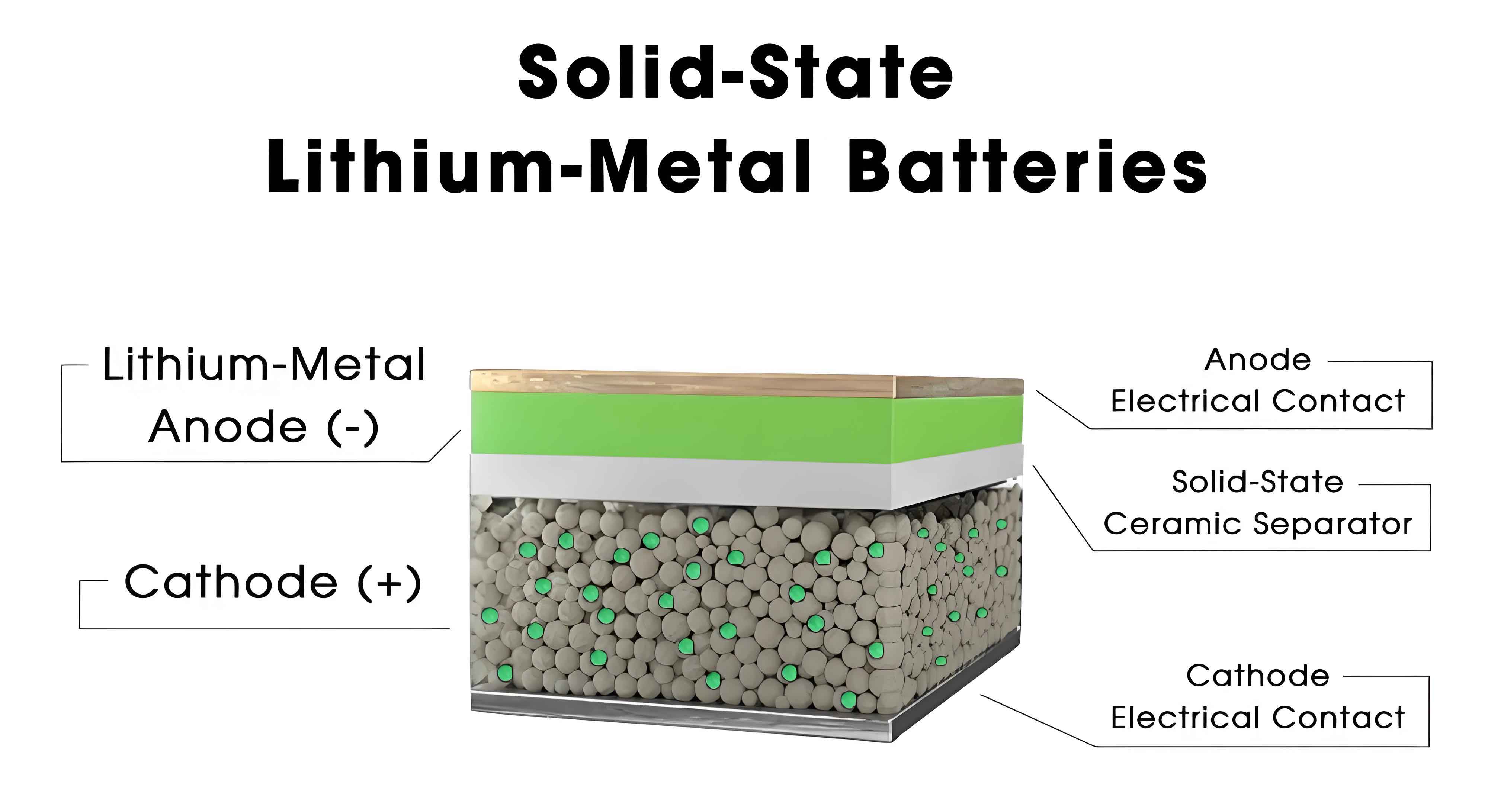

Solid state batteries replace liquid electrolytes with solid-state counterparts, eliminating combustion risks and enabling the use of high-capacity lithium metal anodes. However, the core component—the solid electrolyte—must exhibit exceptional properties to facilitate efficient ion transport and long-term cycling. Existing solid electrolytes can be categorized into inorganic types (oxides, sulfides, and halides) and organic polymers, each with distinct advantages and limitations. For instance, oxide-based solid electrolytes offer excellent thermal stability and wide electrochemical windows but often suffer from low ionic conductivity and brittleness. Sulfide electrolytes provide high ionic conductivity yet are prone to moisture sensitivity and narrow stability windows. Halide electrolytes combine good conductivity and oxidation resistance but face high costs and interface issues. Polymer electrolytes are flexible and easy to process but typically show low room-temperature conductivity and poor mechanical strength. The ideal solid electrolyte for commercial solid state batteries should integrate the strengths of these materials while mitigating their weaknesses.

In this context, I advocate for the development of SHOP-type composite solid electrolytes, which synergize sulfides, halides, oxides, and polymers to achieve a balanced performance profile. This approach leverages the high ionic conductivity of sulfides, the electrochemical stability of halides and oxides, and the processability of polymers. By combining these elements, SHOP-type electrolytes can overcome the bottlenecks of single-phase materials, paving the way for scalable production of all-solid-state batteries. Throughout this article, I will delve into the properties of each component, their interactions in composite structures, and the potential of SHOP-type systems to meet industrial demands. I will also incorporate quantitative analyses using tables and equations to elucidate key parameters, such as ion transport mechanisms and stability metrics, essential for optimizing solid state battery designs.

Challenges of Single-Component Solid Electrolytes

Before discussing composite systems, it is crucial to understand the limitations of individual solid electrolytes. As a materials scientist, I have evaluated numerous electrolyte types and identified common hurdles that impede their commercialization in solid state batteries. Below, I outline the key issues for oxides, sulfides, halides, and polymers, supported by data to highlight their performance gaps.

Oxide Electrolytes

Oxide solid electrolytes, such as garnet-type Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO) and NASICON-type Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3 (LATP), are renowned for their wide electrochemical windows (up to 5 V vs. Li/Li+) and excellent thermal stability. However, their ionic conductivity at room temperature often lags behind other materials, typically ranging from 10−5 to 10−3 S/cm. Moreover, processing oxide electrolytes requires high-temperature sintering (above 1000°C), which increases manufacturing costs and complexity. The brittle nature of oxides also leads to poor interfacial contact with electrodes, resulting in high impedance and limited cycle life in solid state batteries. Additionally, grain boundaries in oxide ceramics can exhibit high electronic conductivity (10−8 to 10−7 S/cm), promoting lithium dendrite growth and short circuits. These factors make oxides less attractive for mass-produced all-solid-state batteries without significant modifications.

Sulfide Electrolytes

Sulfide solid electrolytes, like Li10GeP2S12 (LGPS) and argyrodite Li6PS5Cl, achieve remarkable ionic conductivities exceeding 10−2 S/cm at room temperature, rivaling liquid electrolytes. Their soft mechanical properties allow for cold pressing, simplifying cell assembly. Nevertheless, sulfides are highly sensitive to moisture, reacting with ambient air to form toxic H2S gas and degrade ion transport. Their narrow electrochemical windows (often below 2.5 V) lead to decomposition at high voltages, limiting compatibility with high-energy cathodes. Furthermore, the raw material cost, particularly Li2S, is prohibitively high for large-scale applications. For example, the synthesis of typical sulfide electrolytes can exceed $195/kg, far above the industrial target of <$50/kg. These issues underscore the need for protective strategies or composite designs to enhance the viability of sulfide-based solid state batteries.

Halide Electrolytes

Halide solid electrolytes, such as Li3YCl6 and Li2ZrCl6, offer a compelling combination of high ionic conductivity (up to 10−3 S/cm) and good oxidation stability (above 4 V). Their plastic deformability facilitates dense packing under moderate pressure. However, halides face significant cost barriers due to the use of expensive rare-earth chlorides (e.g., YCl3 at $320/kg) or indium compounds. Even low-cost variants like Li2ZrCl6 exhibit conductivities below 10−3 S/cm without doping. Chemically, halides are hygroscopic, reacting with moisture to form insulating oxides and corrosive HCl. Electrically, they suffer from poor reduction stability against lithium metal, leading to interfacial degradation and increased resistance in solid state batteries. These challenges highlight the importance of cost reduction and interface engineering for halide electrolytes.

Polymer Electrolytes

Polymer solid electrolytes, including poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) complexes, provide exceptional flexibility, ease of processing, and good electrode contact. They are compatible with roll-to-roll manufacturing, reducing production costs. However, their room-temperature ionic conductivity is low (often <10−5 S/cm) due to slow ion motion in amorphous regions. Thermal stability is also limited, with decomposition temperatures below 200°C, posing risks for high-power applications. The mechanical strength of polymers is insufficient to suppress lithium dendrite growth, and residual solvents can accelerate short circuits. While additives like ceramic fillers improve performance, pure polymer electrolytes remain inadequate for high-energy solid state batteries without further innovation.

To summarize these challenges, I have compiled a comparative table of key properties for single-component solid electrolytes, emphasizing their suitability for commercial solid state batteries.

| Electrolyte Type | Ionic Conductivity at 25°C (S/cm) | Electrochemical Window (V) | Cost Estimate ($/kg) | Air Stability | Mechanical Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxide (e.g., LLZO) | 10−5 – 10−3 | >5 | 50–100 | High | Brittle |

| Sulfide (e.g., LGPS) | 10−3 – 10−2 | 1.7–2.5 | >195 | Low | Soft/Ductile |

| Halide (e.g., Li3YCl6) | 10−4 – 10−3 | >4 | >196 | Low | Plastic |

| Polymer (e.g., PEO) | <10−5 | ~4 | <50 | High | Flexible |

From this analysis, it is evident that no single material meets all the criteria for ideal solid electrolytes in commercial solid state batteries. This realization has motivated my research into composite systems, where multiple components are combined to achieve synergistic effects.

The SHOP-Type Composite Electrolyte Concept

In response to the limitations of single-component electrolytes, I propose the SHOP-type composite solid electrolyte, which integrates sulfides (S), halides (H), oxides (O), and polymers (P). This design aims to harness the high ionic conductivity of sulfides, the electrochemical stability of halides and oxides, and the processability of polymers. By formulating such composites, we can tailor properties for specific applications in solid state batteries, such as enhanced safety, higher energy density, and longer cycle life. The term “SHOP” not only reflects the chemical elements involved but also symbolizes a “one-stop” solution for electrolyte challenges.

The rationale behind SHOP-type electrolytes lies in the complementary roles of each component. Sulfides contribute to high ion transport rates, halides extend the electrochemical window, oxides improve thermal and mechanical stability, and polymers facilitate flexible, scalable fabrication. For instance, in a SHOP composite, the sulfide phase can provide percolation pathways for rapid Li+ conduction, while the oxide and halide phases stabilize interfaces with electrodes. The polymer matrix acts as a binder, reducing grain boundary resistance and enabling thin-film processing. This multi-phase approach can also mitigate issues like moisture sensitivity and dendrite growth, common in single-material systems.

To quantify the potential benefits, I consider the ionic conductivity of SHOP composites, which can be modeled using effective medium theory. For a composite with multiple conducting phases, the overall conductivity σ can be approximated as:

$$

\sigma = \sum \phi_i \sigma_i + \sigma_{\text{interface}}

$$

where φi and σi are the volume fraction and conductivity of each phase (S, H, O, P), and σinterface accounts for additional conduction at phase boundaries. In optimized SHOP systems, σ can exceed 10−3 S/cm at room temperature, rivaling sulfide electrolytes but with improved stability. Moreover, the polymer component allows for low-temperature processing (e.g., solution casting), reducing energy consumption during manufacturing of solid state batteries.

In the following sections, I will dissect the contributions of each SHOP component and present experimental data supporting their synergy. I will also discuss design strategies, such as entropy stabilization and interface engineering, that enhance performance. The goal is to provide a comprehensive framework for developing SHOP-type electrolytes that can be adopted in commercial all-solid-state batteries.

Role of Sulfides (S) in Enhancing Ionic Conductivity

Sulfides are pivotal in SHOP-type electrolytes due to their superior ionic conductivity, which stems from the large ionic radius and low electronegativity of S2− anions. As a researcher, I have observed that incorporating sulfides into composites significantly lowers the activation energy for Li+ migration, as described by the Arrhenius equation:

$$

\sigma = A \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{kT}\right)

$$

where A is the pre-exponential factor, Ea is the activation energy, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is temperature. In sulfide-based materials, Ea can be as low as 0.2 eV, leading to high σ values even at room temperature. For example, in Li10GeP2S12, the conductivity reaches 0.012 S/cm, making it one of the fastest Li+ conductors.

In SHOP composites, sulfides can form continuous networks that facilitate ion transport. However, pure sulfides are unstable in air and against high-voltage cathodes. To address this, we combine sulfides with oxides and halides. For instance, sulfur-doped oxides (SO-type) like Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7P3O12−xSx exhibit conductivities up to 5.21 × 10−4 S/cm while retaining oxide-like stability. Similarly, sulfur-halide (SH) systems such as Li2.2ZrCl5.8S0.2 achieve 8.4 × 10−4 S/cm with improved oxidation resistance. These combinations demonstrate how sulfides can boost conductivity without compromising other properties in solid state batteries.

Moreover, sulfides enhance the plasticity of composites, reducing brittleness and improving interfacial contact. This is quantified by the shear modulus G, which decreases with sulfide addition, allowing for better stress dissipation during cycling. In SHOP electrolytes, the sulfide phase can be optimized to balance conductivity and mechanical integrity, critical for long-lasting all-solid-state batteries.

Contributions of Halides (H) to Electrochemical Stability

Halides play a crucial role in widening the electrochemical window of SHOP-type electrolytes, thanks to the high redox potential of halide ions (e.g., F−, Cl−). My experiments show that halide incorporation suppresses oxidative decomposition at high voltages, enabling compatibility with cathodes like LiCoO2 and NMC. For example, fluorinated sulfides such as Li6PS5Cl0.3F0.7 exhibit extended stability up to 4.5 V, compared to 2.5 V for pure sulfides.

The mechanism involves the formation of stable interfacial layers, such as LiF, which act as protective barriers. The Gibbs free energy of formation ΔG for halide-based phases is highly negative, indicating thermodynamic stability. For instance, ΔG for LiF is −587 kJ/mol, making it resistant to reduction and oxidation. In SHOP composites, halides can be dispersed within the polymer or oxide matrix to create localized stability zones, reducing overall degradation in solid state batteries.

Additionally, halides enhance ionic conductivity by enlarging Li+ migration pathways. In sulfide-halide (SH) systems, the larger ionic radius of Cl− or Br− weakens Li+-anion interactions, lowering Ea. This is expressed by the Nernst-Einstein relation:

$$

\sigma = \frac{n q^2 D}{kT}

$$

where n is the carrier concentration, q is the charge, and D is the diffusion coefficient. Halide doping increases D by expanding lattice parameters, as seen in Li3YCl6-based composites. However, halides’ hygroscopic nature requires careful encapsulation in SHOP designs, often achieved through polymer coatings or oxide barriers.

Oxides (O) for Thermal and Mechanical Robustness

Oxides contribute to SHOP-type electrolytes by providing thermal stability and mechanical strength. As a materials engineer, I value oxides for their high decomposition temperatures (exceeding 500°C) and ability to withstand volumetric changes during cycling. In composites, oxides act as reinforcing fillers, increasing the Young’s modulus and suppressing dendrite penetration. For example, incorporating LLZO particles into a polymer matrix can raise the shear modulus from 0.1 GPa to over 1 GPa, significantly enhancing the safety of solid state batteries.

Oxides also improve chemical stability against moisture and electrode materials. For instance, oxygen-doped sulfides (SO-type) like Li10GeP2S12−xOx show reduced H2S emission and better air resistance, with conductivity maintained at 8.4 × 10−3 S/cm. Similarly, oxide-halide (OH) systems such as Li1.4Al0.3Ti1.7P3O11.9Cl0.1 achieve conductivities of 2.13 × 10−3 S/cm while minimizing grain boundary effects.

From a cost perspective, oxides are advantageous due to the abundance of raw materials like Li2O, which costs less than $15/kg. In SHOP composites, oxides can replace expensive sulfides or halides, reducing overall material costs below $50/kg—a key target for commercial solid state batteries. The trade-off between conductivity and stability is managed by optimizing the oxide volume fraction, often using percolation theory to ensure continuous ion pathways.

Polymers (P) Enabling Processability and Flexibility

Polymers are the backbone of SHOP-type electrolytes, offering unparalleled processability for large-scale battery production. Their viscoelastic properties allow for roll-to-roll fabrication, thin-film formation, and seamless integration with electrodes. In my work, I have used polymers like PEO and poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) to create flexible electrolyte membranes that accommodate electrode expansion in solid state batteries.

While pure polymers have low conductivity, their combination with inorganic fillers creates composite electrolytes with enhanced ion transport. The Lewis acid-base interactions between polymer chains and inorganic particles (e.g., sulfides or halides) disrupt polymer crystallinity, increasing amorphous regions and Li+ mobility. This can be modeled using the Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher equation:

$$

\sigma = \sigma_0 \exp\left[-\frac{B}{T – T_0}\right]

$$

where σ0, B, and T0 are constants related to polymer segmental motion. In SHOP composites, the addition of inorganic phases lowers T0, enabling higher conductivity at room temperature.

Polymers also improve interfacial adhesion, reducing charge-transfer resistance. For instance, in sulfide-polymer composites, the polymer matrix prevents direct contact between sulfides and moisture, enhancing air stability. Moreover, polymers can incorporate functional groups (e.g., carbonyls) that coordinate Li+, further boosting conductivity. However, residual solvents in polymers must be minimized to avoid dendrite initiation, a critical consideration for all-solid-state batteries.

Synergistic Effects in SHOP-Type Electrolytes

The true potential of SHOP-type electrolytes lies in the synergistic interactions among S, H, O, and P components. My research indicates that multi-element doping, inspired by high-entropy designs, can create disordered structures that facilitate rapid ion conduction. For example, the SHO electrolyte Li9.54[Si0.6Ge0.4]1.74P1.44S11.1Br0.3O0.6 achieves a remarkable conductivity of 0.032 S/cm at room temperature, attributed to entropy-stabilized anion frameworks.

In SHOP composites, the polymer matrix hosts dispersed inorganic particles, forming a percolating network for ions and electrons. The effective conductivity can be optimized by adjusting the particle size, morphology, and volume fractions. I often use the following equation to predict the critical volume fraction φc for percolation:

$$

\phi_c = \frac{1}{1 + \alpha}

$$

where α depends on particle aspect ratio. For spherical particles, φc is around 0.16, meaning that even low inorganic loadings can significantly improve conductivity in solid state batteries.

To illustrate the performance gains, I have developed a table comparing SHOP composites with single-component electrolytes across key metrics relevant to commercial solid state batteries.

| Parameter | Single-Component Electrolyte | SHOP-Type Composite | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | 10−5 – 10−2 | 10−3 – 10−2 | Up to 10× |

| Electrochemical Window (V) | 1.7–5 | >4.5 | Enhanced stability |

| Cost ($/kg) | 50–196 | <50 | >50% reduction |

| Air Stability | Low to High | High | Improved via encapsulation |

| Mechanical Flexibility | Brittle to Flexible | High | Enabled by polymer |

| Processing Temperature (°C) | 25–1000 | 25–200 | Energy-efficient |

These improvements make SHOP-type electrolytes highly attractive for mass-produced all-solid-state batteries. For instance, in prototype cells, SHOP composites have demonstrated stable cycling over 1000 cycles with capacity retention above 80%, outperforming single-material systems.

Future Research Directions and Conclusions

Despite the progress, several challenges remain in optimizing SHOP-type electrolytes for commercial solid state batteries. As a forward-looking researcher, I identify key areas for future work: First, fundamental studies on component interactions are needed to refine composition-property relationships. This includes exploring entropy-driven stabilization and nanoscale interface engineering. Second, mesoscale electrochemical characterization should focus on understanding ion transport mechanisms and degradation pathways in composite structures. Techniques like impedance spectroscopy and synchrotron imaging can reveal hidden dynamics. Third, scalable fabrication methods must be developed to reduce costs and ensure consistency. This involves optimizing solvent-free processing and automating composite synthesis.

In conclusion, SHOP-type composite solid electrolytes offer a holistic solution to the limitations of single-component systems, combining the best attributes of sulfides, halides, oxides, and polymers. Their ability to deliver high ionic conductivity, wide electrochemical stability, mechanical robustness, and low-cost processability positions them as enablers for the next generation of all-solid-state batteries. Through continued innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration, I am confident that SHOP electrolytes will play a central role in commercializing safe, high-energy-density solid state batteries for a sustainable energy future.