As we navigate the pressing challenges of climate change and energy security, the transportation sector stands as a major contributor to global carbon emissions. While Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) represent a clear path forward, they are currently hampered by significant hurdles: range anxiety, inadequate charging infrastructure, the strain of fast-charging on electrical grids, and high manufacturing costs. Concurrently, the environmental benefit of BEVs is frequently questioned when the electricity they consume is generated from fossil fuels. In this context, I propose a fourth architecture for hybrid electric vehicles, termed the “Lightyear” (LY) structure. This design not only addresses the critical limitations of current BEVs but also, when synergized with decentralized biomass energy systems, presents a viable pathway to rapidly decarbonize transportation and reshape our energy landscape. This concept, to my knowledge, is original and unreported prior to this discussion.

The prevailing architectures for hybrid electric vehicles are primarily series, parallel, and series-parallel (power-split) configurations. The Lightyear structure introduces a fundamentally different approach centered on the dual-use of drive motors as generators and the strategic application of external mechanical power for rapid, grid-independent recharging. The core principle is the efficient and rapid transformation, storage, and reuse of energy, minimizing vehicle weight by maximizing component utilization across driving, acceleration, deceleration, and charging cycles. This hybrid electric vehicle architecture is designed from the ground up to utilize clean, distributed energy sources.

Principles and Configurations of the Lightyear Hybrid Electric Vehicle

1. Single-Motor LY Architecture

This configuration is essentially a pure BEV where the singular drive motor also functions as a generator. Imagine a 130 kW motor/generator unit. During driving, it operates as a motor to provide propulsion. When the vehicle is stationary, an external prime mover (e.g., a small internal combustion engine, a turbine, or even a mechanical connection to stationary power) can be engaged to drive the unit in reverse, turning it into a 130 kW generator. This setup allows for rapid battery replenishment independently of the grid. It can also accept grid charging via a standard port. The combined charging power can be substantial (e.g., 130 kW from the generator + 40 kW from grid = 170 kW), enabling an 80% state-of-charge in approximately 15 minutes for a 25 kWh battery pack.

2. Dual-Motor LY Architecture

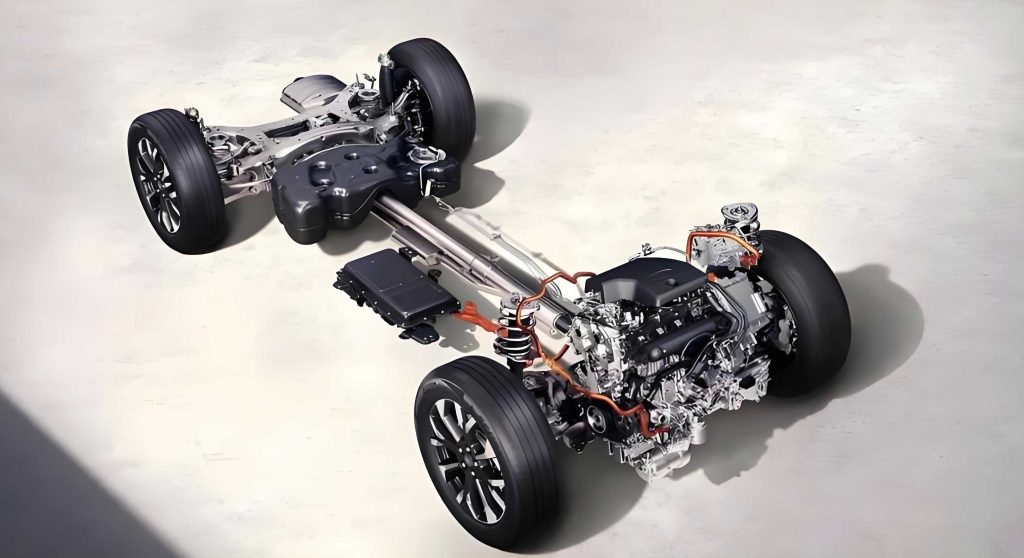

This is a more versatile and likely mainstream configuration for the Lightyear hybrid electric vehicle. It employs two motor/generator units:

- Motor A (Front): A 55 kW unit serving primarily as a generator but capable of providing motive power. It is coupled via a simple transmission system. When driven by an external mechanical source (like a compact range-extender engine), it generates electricity at a power level between 20-55 kW.

- Motor B (Rear): A 75 kW primary drive motor responsible for propulsion, capable of maintaining highway speeds on its own.

This dual-motor hybrid electric vehicle operates in multiple modes. In pure EV mode, it drives on battery power. When stationary, an onboard range-extender engine (rated at 20, 30, 40, or 55 kW) can activate to drive Motor A for generating electricity, charging the battery at up to 55 kW. This can be combined with grid charging (e.g., 45 kW DC fast-charging) for a total peak charge power of 100 kW. The vehicle’s control system with bi-directional capability manages the flow of energy, sending generated power either to the battery or directly to Motor B.

Let’s consider a practical example with a dual-motor LY hybrid electric vehicle. Assume a battery capacity of 26 kWh providing 160 km of pure electric range, with an energy consumption of 13 kWh/100km. Once the battery is depleted after 2 hours of driving, a 20 kW range-extender activates. Over 2 hours, it generates:

$$ E_{gen} = P_{gen} \times t = 20 \text{ kW} \times 2 \text{ h} = 40 \text{ kWh} $$

This effectively extends the total range. If the vehicle carries 40L of fuel with a hybrid fuel consumption of 8L/100km, the total theoretical range exceeds 660 km, effectively eliminating range anxiety. The fuel consumption in charge-sustaining mode can be modeled as:

$$ C_{hs} = \frac{P_{eng} / \eta_{gen}}{\eta_{batt} \times v / 100 \times E_{cons}} $$

where $C_{hs}$ is hybrid fuel consumption (L/100km), $P_{eng}$ is engine power output (kW), $\eta_{gen}$ is generator efficiency, $\eta_{batt}$ is battery charge/discharge efficiency, $v$ is vehicle speed (km/h), and $E_{cons}$ is vehicle energy consumption (kWh/km).

3. LY Architecture for Commercial Trucks

For heavy-duty applications where energy demands are colossal, the Lightyear concept scales effectively. A LY hybrid electric truck could employ multiple wheel-hub motor/generators. Each wheel unit can independently provide drive torque or regenerate energy during braking. One or more high-power range-extender generator sets would supply electricity for sustained operation or rapid battery charging during mandatory rest stops, solving the critical challenge of charging infrastructure for freight.

4. Systemic Impact on Energy Infrastructure

The transformative potential of the LY hybrid electric vehicle becomes clear when considering fleet-scale adoption. Let’s analyze a comparative case study between a conventional SUV (GS3) and its hypothetical LY hybrid electric version (new GE3).

| Parameter | Conventional SUV (GS3) | Lightyear Hybrid Electric SUV (New GE3) | LY with Biomass Charging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel/Energy Consumption | 7.8 L/100km (Gasoline) | 13 kWh/100km (Battery) + Range-extender | 13 kWh/100km |

| Annual Fuel/Energy Need | 4,555 Liters | 9,918 kWh (Grid) | 9,918 kWh (Biomass) |

| Energy Unit Cost | $7.5 / Gallon | $0.69 / kWh | $0 (Feedstock Cost Negligible) |

| Annual Energy Cost | $34,162 | $6,843 | ~$0 |

The cost advantage of the hybrid electric vehicle is overwhelming. More profoundly, if China’s 220 million vehicle fleet were replaced with LY architecture vehicles, each with an average generation capacity of 55 kW, the total distributed generation capacity would be:

$$ P_{total} = N_{vehicles} \times P_{avg} = 2.2 \times 10^8 \times 55 \times 10^3 \text{ W} = 1.21 \times 10^{13} \text{ W} = 1210 \text{ GW} $$

This is 6.8 times China’s 2017 total installed power generation capacity of ~1780 GW. Assuming 12 hours of idle time per day for 300 days a year, the potential annual energy output from this fleet, if fully utilized with a fuel source, would be:

$$ E_{fleet} = P_{total} \times t_{idle} \times \eta = 1210 \text{ GW} \times (12 \times 300) \text{ h} \times 0.35 \approx 1.5 \times 10^6 \text{ GWh} $$

This is several times current total national electricity generation. The key, therefore, is not the generating capacity but the fuel source. This is where biomass energy becomes indispensable.

Biomass Energy as the Sustainable Fuel for the Lightyear Hybrid Electric Vehicle Ecosystem

The premise that biomass can wholly replace fossil fuels for transportation is theoretically sound. Annual global photosynthetic biomass production is estimated at 1,440-1,800 billion tons (dry weight), containing energy equivalent to 3-8 times the world’s total primary energy consumption in the early 1990s. The challenge is its dispersed nature and low energy density. The LY hybrid electric vehicle ecosystem, with its need for distributed fuel for its range-extenders, is perfectly matched to this characteristic. Sources include urban food waste, sewage, agricultural residues (e.g., corn stover), forestry waste, and animal manure.

Case Study: Corn Stover-Powered Charging Stations

Corn stover is a major agricultural residue. Its biogas yield is a critical parameter. Data from various biomasses indicates a typical methane yield for pretreated corn stover.

| Feedstock | Total Biogas Yield (m³/ton TS) | Methane Content (%) | Methane Yield (m³/ton TS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Food Waste | 550 – 900 | 50 – 65 | 275 – 585 |

| Swine Manure | 250 – 500 | 60 – 70 | 150 – 350 |

| Corn Stover (Pretreated) | 550 – 650 | 50 – 55 | 275 – 358 |

| Waste Activated Sludge | 300 – 500 | 60 – 65 | 180 – 325 |

For this analysis, we assume a conservative methane yield for pretreated corn stover of 557 Nm³/ton of Total Solids (TS), with a biogas-to-electricity conversion efficiency of 2.0 kWh/Nm³ of biogas in a modern genset. China’s 2017 corn production was 215.9 million tons. Using a standard Grain-to-Straw ratio of 1:1.2, the dry stover potential was approximately 259 million tons.

$$ \text{Dry Stover Mass} = \text{Grain Production} \times \text{Straw Ratio} = 215.9 \times 10^6 \text{ t} \times 1.2 \approx 2.59 \times 10^8 \text{ t} $$

The theoretical power generation potential is:

$$ E_{stover} = M_{stover} \times Y_{CH_4} \times \eta_{elec} = 2.59 \times 10^8 \text{ t} \times 557 \frac{\text{Nm³}}{\text{t}} \times 2.0 \frac{\text{kWh}}{\text{Nm³}} \approx 2.89 \times 10^{11} \text{ kWh} = 289.6 \text{ TWh} $$

This is equivalent to about 4.5% of China’s 2017 total electricity generation.

The economic viability of a decentralized charging station is paramount. Consider a station processing 2 tons of dry corn stover daily (at a feedstock cost of ~$60/ton).

| Parameters & Assumptions | |

|---|---|

| Daily Dry Stover Input | 2 tons |

| Specific Biogas Yield | 557 Nm³/ton |

| Daily Biogas Production | 1,114 Nm³ |

| Power Conversion Efficiency | 2.0 kWh/Nm³ |

| Daily Electricity Generation | 2,228 kWh |

| Station Configuration | 4 x 60 kW Gensets, 4 x 50 kW Chargers |

| Estimated Capital Cost | $1.36 million |

| Annual Operational Costs | |

| Feedstock Cost (2t/day * $60/t * 365d) | $43,800 |

| Labor & Maintenance (4 personnel) | $60,000 |

| Utilities & Materials | $15,000 |

| Depreciation (7-year straight-line) | $194,286 |

| Total Annual Cost | $313,086 |

| Annual Revenue | |

| Electricity Price | $0.18 / kWh |

| Annual Electricity Sales (2228 kWh/d * 365d) | 813,220 kWh |

| Total Annual Revenue | $146,380 |

| Simple Payback Period | $\frac{1,360,000}{146,380 – 118,800} \approx 49.3 \text{ years}$ |

The initial calculation shows a long payback. However, revenue can be significantly enhanced by providing direct fast-charging services at a premium (e.g., $0.30/kWh). If all generated power is sold as charging service to 120 LY hybrid electric vehicles daily (each taking 20 kWh), the revenue becomes:

$$ R_{charging} = E_{daily} \times P_{charge} \times 365 = 2228 \text{ kWh/d} \times 0.30 \text{ $/kWh} \times 365 \approx \$244,000/\text{year} $$

This yields a payback period of under 10 years, demonstrating commercial feasibility without subsidies. Scaling this model nationally to utilize all corn stover would require about 360,000 such micro-plants, representing a total investment of around $500 billion, but creating a resilient, decentralized energy network for the hybrid electric vehicle fleet.

Prospective Impact and Concluding Synthesis

The integration of the Lightyear hybrid electric vehicle architecture with a biomass-based energy system presents a comprehensive solution bundle. Its prospective impacts can be summarized quantitatively.

| Impact Category | Quantitative Potential | Notes and Assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Fossil Fuel Displacement | Reduction of 300-400 million tons of oil/year | Based on displacing most transport fuel in a large market like China. |

| Cost Savings | $200-300 Billion/year in fuel costs | Assuming replaced gasoline/diesel at current market prices. |

| Additional Electricity Generation | +2,000 – 3,000 TWh/year | From dedicated biomass plants powering the vehicle fleet’s range-extenders. |

| Vehicle Manufacturing Cost | Lower than equivalent ICE vehicle | Due to smaller battery pack and simplified powertrain relative to long-range BEVs. |

| Agricultural Waste Management | Utilization of hundreds of millions of tons of residue | Solving waste disposal issues and producing organic fertilizer (digestate). |

| Grid Stability | Positive impact via distributed generation & storage | Vehicle batteries and onboard generators can provide grid services. |

In conclusion, the Lightyear architecture is not merely an incremental improvement but a reimagining of the hybrid electric vehicle as an active node in a decentralized, renewable energy system. It pragmatically bridges the gap between our current infrastructure and a sustainable future. By solving the core issues of cost, range, and charging for the vehicle owner, while simultaneously creating a scalable demand for distributed biomass energy, it aligns economic incentives with environmental imperatives. The technical foundations—efficient motor/generators, power electronics, biogas technology—are all established. Realizing this vision requires coordinated policy support, targeted R&D for system integration and biomass pre-treatment, and business model innovation. The path forward is clear: the future of transportation is not just electric, but intelligently hybrid and symbiotically integrated with the biosphere’s energy cycles.