The rapid global adoption of the battery electric car represents a monumental shift in transportation and energy systems. As the cornerstone of this transition, charging infrastructure is undergoing continuous expansion and technological refinement. However, the proliferation of high-power, non-linear charging systems introduces significant power quality challenges, with harmonic distortion emerging as a critical concern for grid stability and efficiency. This article, from my perspective as an engineer in the field, delves into the nature of this problem and explores an intelligent control strategy centered on fuzzy logic to ensure the sustainable integration of battery electric car fleets.

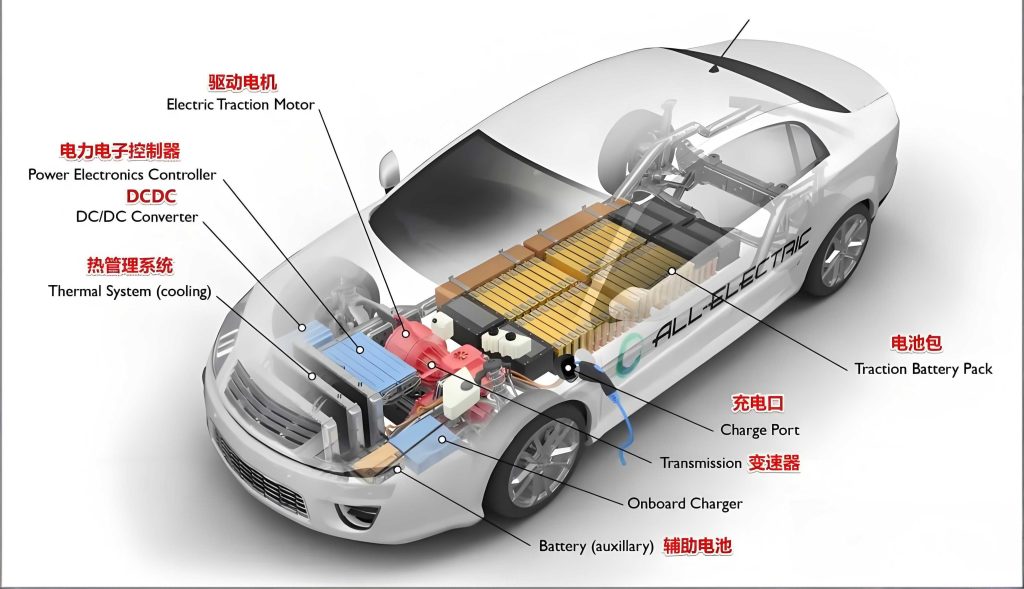

The growth trajectory of the battery electric car market is steep. To support this, charging stations—from residential chargers to public fast-charging hubs—are being deployed at an unprecedented rate. Each battery electric car charger is essentially a power electronic interface that converts alternating current (AC) from the grid to direct current (DC) for the vehicle’s battery. This conversion process, typically involving rectifiers and high-frequency switching devices, is inherently non-linear. When a large number of such chargers operate simultaneously, especially in dense urban areas or at highway charging plazas, they inject harmonic currents back into the grid. These harmonics are sinusoidal voltages or currents with frequencies that are integer multiples of the fundamental power frequency (e.g., 50 Hz or 60 Hz).

The Harmonic Problem in Battery Electric Car Infrastructure

The core of the issue lies in the design of power converters for the battery electric car. Common charger topologies, like the six-pulse or twelve-pulse rectifier and various DC-DC converters, draw current in short, non-sinusoidal pulses. This distorted current waveform can be decomposed into a fundamental component and a series of harmonic components. The predominant harmonics are often the 5th, 7th, 11th, and 13th, though higher-order harmonics are also present.

The impact of these harmonics on the power system is multifaceted and detrimental:

| Impact Category | Specific Effects | Consequences for Battery Electric Car Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|

| Power Quality Degradation | Voltage waveform distortion, voltage fluctuations, flicker. | Reduced charging efficiency, potential malfunctions in sensitive charger electronics, and inconsistent performance for other connected battery electric cars. |

| Increased System Losses | Joule heating due to harmonic currents flowing through network impedance ($P_{loss} = I_{rms}^2 R$, where $I_{rms}$ includes harmonic components). | Higher operational costs for charging station operators, increased thermal stress on cables and transformers serving the battery electric car charging hub. |

| Equipment Overloading & Premature Aging | Additional core losses in transformers, dielectric stress on capacitors, torsional vibrations in motors. | Shortened lifespan of station transformers, capacitor banks, and protection devices, leading to higher maintenance costs and downtime. |

| Resonance Phenomena | Amplification of specific harmonic currents/voltages when system impedance interacts with power factor correction capacitors. | Catastrophic overvoltages or overcurrents that can trip protection systems and damage both charging equipment and the battery electric car’s onboard charger. |

| Measurement & Metering Errors | Inaccurate readings from meters calibrated for pure sinusoidal waveforms. | Incorrect billing for energy consumed during the charging of a battery electric car. |

Therefore, effective harmonic mitigation is not merely an optional improvement; it is a necessity for the reliable, efficient, and safe operation of large-scale battery electric car charging networks. Compliance with power quality standards like IEEE 519-2014 or IEC 61000-3-2/4 is mandatory, and proactive mitigation is the most cost-effective strategy in the long run.

Traditional Harmonic Mitigation Approaches and Their Limitations

Before introducing advanced methods, it is essential to review conventional harmonic mitigation techniques applied in power systems, including those serving battery electric car stations.

Passive Filters

These are the simplest and most cost-effective solution. A passive filter is a combination of inductors (L), capacitors (C), and sometimes resistors (R) tuned to a specific harmonic frequency. For instance, a single-tuned passive filter for the 5th harmonic is designed such that its resonant frequency $f_r$ is close to 250 Hz (for a 50 Hz system):

$$f_r = \frac{1}{2\pi\sqrt{LC}} \approx 250 \text{ Hz}$$

At this frequency, the filter presents a very low impedance path, effectively “shunting” the 5th harmonic current away from the grid. While inexpensive and robust, passive filters have significant drawbacks for the dynamic environment of a battery electric car station:

- Fixed Tuning: They are effective only for the specific harmonic they are designed for. The harmonic spectrum from multiple battery electric car chargers can vary widely.

- Risk of Resonance: They can inadvertently create parallel or series resonance with the grid impedance at other frequencies, amplifying unexpected harmonics.

- Bulky Size: For high power levels, the L and C components become physically large.

- No Adaptive Capability: They cannot respond to changes in the number of charging battery electric cars or the type of charger in use.

Active Power Filters (APF)

APFs represent a significant technological leap. They operate by injecting a compensating current ($i_c(t)$) that is equal in magnitude but opposite in phase to the detected harmonic current ($i_h(t)$). The core principle is:

$$i_{load}(t) = i_{fundamental}(t) + i_{harmonic}(t)$$

$$i_{APF}(t) = -i_{harmonic}(t)$$

$$i_{source}(t) = i_{load}(t) + i_{APF}(t) = i_{fundamental}(t)$$

This requires real-time harmonic detection, typically using algorithms like the Instantaneous Power Theory (p-q theory) or Synchronous Reference Frame (SRF) theory. While highly effective and adaptive, traditional APF control relies on precise mathematical models and linear control techniques like Proportional-Integral (PI) controllers. Their performance can degrade under highly non-linear, time-varying loads—precisely the conditions in a busy battery electric car charging station where chargers switch on/off randomly and load currents change rapidly.

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages for Battery Electric Car Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Passive Filters | Low cost, simple, high reliability, no external power required. | Fixed compensation, risk of resonance, large size, poor adaptability to changing loads from multiple battery electric cars. |

| Active Power Filters (Conventional Control) | High effectiveness, compensates multiple harmonics simultaneously, adaptive to changing harmonic spectra. | High cost, complex control system, performance dependent on accurate system model and fast processing; may struggle with the extreme non-linearity of aggregated battery electric car chargers. |

The limitations of these traditional methods, particularly their lack of true intelligence and adaptability in uncertain environments, motivate the exploration of fuzzy control theory.

Fuzzy Control Theory: A Primer for Intelligent Systems

Fuzzy logic, pioneered by Lotfi Zadeh, provides a mathematical framework for representing and reasoning with imprecise or “fuzzy” concepts. Unlike classical binary logic where a statement is either true (1) or false (0), fuzzy logic allows for degrees of truth, expressed through membership functions with values between 0 and 1. This aligns perfectly with the real-world operation of a battery electric car charging station, where conditions like “high harmonic distortion,” “rapid load change,” or “medium compensation required” are not crisply defined but exist on a spectrum.

A fuzzy logic controller (FLC) mimics human expert decision-making. Its architecture consists of four main stages:

- Fuzzification: Converts crisp, measured input values (e.g., Total Harmonic Distortion of current, $THD_I = 8.5\%$) into fuzzy linguistic variables (e.g., “THD_I is Medium”). This is done using predefined membership functions (MFs). A common triangular MF for “Medium” THD_I might be defined as:

$$\mu_{Medium}(x) = \begin{cases}

0, & x \leq a \\

\frac{x-a}{b-a}, & a < x \leq b \\

\frac{c-x}{c-b}, & b < x \leq c \\

0, & x > c

\end{cases}$$

where $a$, $b$, and $c$ are parameters defining the triangle’s vertices. - Rule Base: Contains the expert knowledge in the form of “IF-THEN” rules. For harmonic control, a rule might be:

IF ($THD_I$ is High) AND ($\frac{dP}{dt}$ is Positive) THEN ($I_{comp\_amp}$ is Large_Increase). - Inference Engine: Evaluates all applicable rules based on the current fuzzified inputs. It combines the “degrees of firing” of each rule using operators like MIN (for AND) or MAX (for OR) to produce a fuzzy output set for each control variable.

- Defuzzification: Converts the aggregated fuzzy output set back into a crisp, actionable control signal. The most common method is the centroid (center of gravity) calculation:

$$y^* = \frac{\int \mu_{output}(y) \cdot y \, dy}{\int \mu_{output}(y) \, dy}$$

where $y^*$ is the final crisp output value (e.g., the required compensation current amplitude).

The power of fuzzy control in the context of a battery electric car charging station lies in its inherent strengths:

- Model-Free Design: It does not require an exact mathematical model of the highly non-linear and aggregated load of multiple battery electric car chargers.

- Robustness: It is inherently tolerant to parameter variations, noise, and load changes, maintaining stable performance.

- Natural Language Rules: The rule base can be developed and understood based on engineering intuition and operational experience.

- Adaptability: The rule base and membership functions can be tuned and optimized for specific site conditions.

A Fuzzy Logic-Based Harmonic Control System Design

I propose a system design that integrates a fuzzy logic controller as the brain of an Active Power Filter (APF) system dedicated to a battery electric car charging station. This creates an intelligent, self-adapting harmonic mitigation unit.

System Architecture and Workflow

The system comprises three main functional blocks:

- Measurement & Detection Block: Current transformers (CTs) and voltage transformers (VTs) continuously monitor the point of common coupling (PCC) at the battery electric car charging station. A harmonic detection algorithm (e.g., an adaptive algorithm based on the Least Mean Squares (LMS) theory) extracts in real-time the amplitudes and phase angles of dominant harmonic components ($I_{h1}, I_{h2}, …$). It also calculates key indices like $THD_I$ and tracks the rate of change of total active power ($\frac{dP}{dt}$).

- Fuzzy Logic Controller (FLC) Block: This is the core innovation. The FLC takes the processed measurements as crisp inputs and generates crisp commands for the APF’s power circuit.

- Input Variables:

- $THD_I$ (Total Harmonic Distortion of Current): Fuzzy sets {Low, Medium, High}.

- $\frac{dP}{dt}$ (Load Change Rate): Fuzzy sets {Negative (decreasing), Zero (stable), Positive (increasing)}. This directly relates to the dynamic connection/disconnection of a battery electric car.

- $I_{5th}$ (Amplitude of 5th Harmonic): Fuzzy sets {Small, Medium, Large}.

- Output Variables:

- $K_p$ (Proportional Gain for APF current control): Fuzzy sets {Decrease, Maintain, Increase}. This allows dynamic tuning of the APF’s inner loop.

- $I_{ref\_amp}$ (Amplitude of the fundamental reference current for compensation): Fuzzy sets {Small, Medium, Large}.

- Input Variables:

- APF Power & Execution Block: A voltage-source inverter (VSI) acts as the APF. It receives the crisp reference signals ($K_p$, $I_{ref\_amp}$) from the FLC. Using pulse-width modulation (PWM), the VSI generates and injects the precise compensating currents ($i_c(t)$) into the grid at the PCC, thereby canceling the harmonics generated by the battery electric car chargers.

Designing the Fuzzy Controller: An Illustrative Example

Defining the rule base is critical. It encapsulates the strategy for managing harmonics from a fluctuating number of battery electric cars. Below is a subset of a potential rule base:

| Rule # | IF (Conditions) | THEN (Actions) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | $THD_I$ is High AND $\frac{dP}{dt}$ is Positive | $K_p$ is Increase AND $I_{ref\_amp}$ is Large |

| 2 | $THD_I$ is Medium AND $I_{5th}$ is Large | $K_p$ is Maintain AND $I_{ref\_amp}$ is Medium |

| 3 | $THD_I$ is Low AND $\frac{dP}{dt}$ is Negative | $K_p$ is Decrease AND $I_{ref\_amp}$ is Small |

| 4 | $THD_I$ is High AND $\frac{dP}{dt}$ is Zero | $K_p$ is Increase AND $I_{ref\_amp}$ is Medium |

The membership functions for inputs and outputs are initially designed based on engineering judgment and then refined through simulation. For instance, the $THD_I$ variable might have triangular MFs defined with the following centroids for a system compliant with IEEE 519:

Low: Center at 3% (covering 0-8%)

Medium: Center at 8% (covering 3-12%)

High: Center at 15% (covering 8% and above)

Performance Simulation and Expected Outcomes

Through simulation in tools like MATLAB/Simulink or PLECS, the performance of this fuzzy-controlled APF can be benchmarked against a conventionally (PI-controlled) APF for a modeled battery electric car charging station with 10-50 variable chargers. Key performance indicators (KPIs) would include:

- Settling Time ($T_s$): The time taken for the $THD_I$ to fall below 5% after a step-change in load (e.g., 5 new battery electric cars initiating fast charging simultaneously). The fuzzy controller is expected to exhibit a faster and smoother response: $T_{s_{fuzzy}} < T_{s_{PI}}$.

- Overshoot ($M_p$): The maximum peak of $THD_I$ during the transient. The fuzzy controller’s adaptive gain adjustment should minimize this: $M_{p_{fuzzy}} \ll M_{p_{PI}}$.

- Steady-State $THD_I$: Both should achieve a low steady-state error, but the fuzzy controller may maintain a more consistent level under varying non-linear load conditions typical of diverse battery electric car models charging.

The fuzzy system’s inherent strength is its ability to handle the “grey area” scenarios. For example, when harmonic levels are borderline (“Medium”) and load is fluctuating (“Positive”), the fuzzy controller can apply a nuanced, weighted combination of rules to produce an optimal, non-linear control response that a linear PI controller, tuned for a specific operating point, cannot achieve.

Advantages, Challenges, and Future Directions

The integration of fuzzy logic into harmonic control for battery electric car charging stations presents a compelling set of advantages, though not without challenges.

| Aspect | Advantages | Challenges & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| System Performance | Superior adaptability to random, non-linear load changes from battery electric cars. Enhanced robustness against parameter variations. Smooth, non-linear control action reduces stress on APF components. | Design of the initial rule base and membership functions requires expert knowledge and iterative simulation. Performance is heavily dependent on the quality of this design. |

| Implementation & Cost | Algorithm can be implemented on standard digital signal processors (DSPs) or FPGAs. No need for exhaustive system identification modeling, potentially reducing engineering time. | Computational load is higher than a simple PI controller, requiring adequate processing power for real-time operation at high switching frequencies. |

| Maintenance & Tuning | Rule base is intuitive and can be modified by engineers based on operational data without deep control theory expertise. | Lacks inherent learning capability. Rules are static unless manually updated or coupled with an online optimization algorithm. |

Future research and development will likely focus on hybrid intelligent systems to overcome these challenges and further enhance the management of power quality for the battery electric car ecosystem:

- Neuro-Fuzzy Systems (ANFIS): Combining fuzzy logic with artificial neural networks (ANNs) to enable the system to learn and optimize its own rule base and membership functions from historical operational data of the battery electric car charging station.

- Fuzzy-PI Hybrid Controllers: Using the fuzzy logic supervisor to dynamically adjust the gains ($K_p$, $K_i$) of a traditional PI controller that handles the APF’s inner current loop, marrying the adaptability of fuzzy with the precision of PI.

- Multi-Agent & Coordinated Control: For large charging parks with multiple APF units, a hierarchical fuzzy control system could coordinate their operation to optimize overall harmonic compensation and load balancing.

In conclusion, the widespread adoption of the battery electric car presents a unique power quality challenge in the form of harmonic pollution from charging stations. While traditional passive and active filtering methods provide a foundation, their limitations in dynamic, uncertain environments call for more intelligent solutions. Fuzzy logic control, with its ability to model human-like reasoning and handle imprecise information, offers a powerful and practical framework for designing adaptive harmonic mitigation systems. By implementing a fuzzy-controlled APF, charging station operators can ensure higher power quality, improved grid stability, reduced losses, and extended equipment life. This intelligent approach is a critical step towards building the resilient and efficient infrastructure required to support the global transition to electric mobility powered by the battery electric car. The continued evolution of this technology, particularly through hybridization with other AI techniques, promises even more autonomous and optimal management of the complex interactions between the growing fleet of battery electric cars and the power grid.