As an experienced technician in the field of hybrid electric vehicles, I have encountered numerous cases where high-voltage battery systems present complex challenges. The hybrid electric vehicle represents a significant advancement in automotive technology, combining internal combustion engines with electric propulsion to enhance efficiency and reduce emissions. However, the high-voltage battery, a core component of any hybrid electric vehicle, can be a source of intricate faults that require meticulous diagnosis. In this article, I will delve into a comprehensive case study involving a high-voltage battery failure in a hybrid electric vehicle, detailing the diagnostic process, repair methodology, and broader implications for maintaining these advanced systems. My goal is to provide a thorough resource that emphasizes the importance of systematic approaches in hybrid electric vehicle servicing.

The proliferation of hybrid electric vehicles has revolutionized the automotive industry, offering improved fuel economy and lower environmental impact. Central to the operation of a hybrid electric vehicle is the high-voltage battery system, which stores electrical energy for driving the electric motor, powering auxiliary systems, and capturing regenerative braking energy. Understanding this system is crucial for technicians, as faults can lead to drivability issues, safety concerns, and increased operational costs. In my practice, I have found that a methodical approach—combining theoretical knowledge with hands-on testing—is essential for resolving such faults in hybrid electric vehicles.

In this particular instance, I addressed a fault in a hybrid electric vehicle that exhibited symptoms including an inability to drive in electric mode, illumination of the high-voltage battery warning light on the dashboard, persistent engine operation, and chronic depletion of the low-voltage battery. These symptoms are common indicators of high-voltage battery malfunctions in hybrid electric vehicles, often stemming from issues like cell imbalances, communication failures, or component degradation. The hybrid electric vehicle in question was a plug-in model, which adds layers of complexity due to its dual energy sources and sophisticated battery management.

To begin the diagnosis, I connected a professional fault detection tool to the vehicle’s onboard diagnostic port. The battery management system (BMS) in a hybrid electric vehicle is responsible for monitoring and controlling the high-voltage battery, and it often stores critical fault codes. In this case, the tool retrieved two relevant fault codes: P1897, indicating activation of high-voltage battery temperature deviation. Additionally, I examined live data streams from the BMS, which revealed alarming readings: cells 85 through 96 showed voltages of 0 V, and temperatures for battery modules 15 and 16 were recorded at -40 °C. Such anomalies in a hybrid electric vehicle typically point to a localized failure within the battery assembly, as the BMS relies on distributed sensors to gather data.

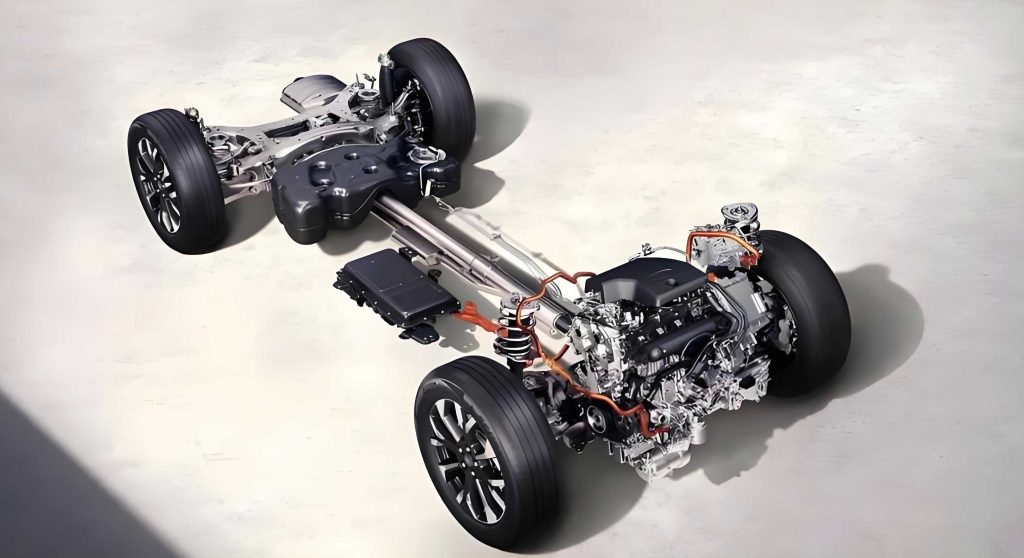

The high-voltage battery system in this hybrid electric vehicle is designed with multiple modules, each containing 12 individual cells and equipped with a battery collector unit. These collectors measure cell voltages and temperatures, transmitting data via a dedicated Controller Area Network (CAN) bus to the BMS. For reference, the total battery pack comprises 96 cells arranged in 8 modules, providing a nominal voltage of 350 V, which is standard for many hybrid electric vehicles. The architecture emphasizes redundancy and safety, but failures in communication or sensor circuits can disrupt overall functionality. Below is a table summarizing key components of a typical high-voltage battery system in a hybrid electric vehicle:

| Component | Function | Typical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Battery Modules | Contain individual cells for energy storage | 12 cells per module, 3.65 V per cell |

| Battery Collector | Measures cell voltages and temperatures | Uses chips like MAX17823B for data acquisition |

| BMS (Battery Management System) | Monitors and manages battery state | Processes data via CAN bus, ensures safety |

| Power Relay Assembly | Controls high-voltage circuit engagement | Includes contactors for isolation |

| Cooling System | Maintains optimal battery temperature | Utilizes fans or liquid cooling |

Based on the data stream anomalies, I hypothesized that module 8 was faulty, as it corresponds to cells 85-96 and temperature sensors 15-16. In a hybrid electric vehicle, each module’s collector is powered and communicates via a specific circuit. To test this, I first measured the voltage at the collector’s power supply pins. Using a multimeter, I checked between terminal 7 (power) and ground, obtaining a reading of 12 V, which is normal for the low-voltage supply in a hybrid electric vehicle. Next, I measured the resistance between terminal 12 (ground) and ground, resulting in 0.5 Ω, indicating a proper ground connection. These steps are fundamental in diagnosing electrical issues in hybrid electric vehicles, as poor connections can mimic component failures.

I then proceeded to inspect the CAN bus communication for module 8. The CAN bus in a hybrid electric vehicle facilitates data exchange between collectors and the BMS, and faults here can lead to erroneous readings. Disconnecting the collector connector, I measured the resistance between terminals 9 and 10 (CAN high and low lines), which should typically be around 120 Ω due to termination resistors. The measurement confirmed 120 Ω, suggesting the CAN bus was intact. Similarly, between terminals 3 and 4, I found 120 Ω, further verifying circuit integrity. These values can be derived from Ohm’s law, expressed as:

$$ V = IR $$

where \( V \) is voltage, \( I \) is current, and \( R \) is resistance. In a hybrid electric vehicle’s CAN bus, proper termination is critical for signal integrity, and deviations can cause communication failures. Given that all circuit tests passed, I suspected the collector unit itself was defective. To confirm, I employed a swap test: interchanging module 8 with module 7 in the battery assembly. After reassembly and power-up, the data stream shifted—cells 73-84 now showed 0 V, and temperatures for modules 13-14 read -40 °C, while the previously faulty cells 85-96 returned to normal readings. This definitive test proved that module 8’s collector was faulty, a common issue in aging hybrid electric vehicles.

Upon disassembling the high-voltage battery, I measured the individual cell voltages within module 8 using a precision voltmeter. Each cell registered approximately 3.6 V, which aligns with the nominal voltage for lithium-ion cells in a hybrid electric vehicle. This indicated that the battery cells were healthy, and the fault lay solely in the collector’s electronics. The collector uses specialized integrated circuits, such as the MAX17823B for data acquisition and the S9S12G128 as a main controller, coupled with CAN transceivers like the TJA1051. In a hybrid electric vehicle, these chips manage critical functions, and their failure can paralyze the entire system. To delve deeper, I analyzed the collector’s operation by powering it externally and probing signal waveforms with an oscilloscope. The CAN transceiver showed normal activity, and the SPI interface chip MAX17841B transmitted signals correctly, but the MAX17823B acquisition chip failed to receive or process data, confirming its malfunction.

The failure of the MAX17823B chip in this hybrid electric vehicle highlights the vulnerability of microelectronics in harsh automotive environments. Factors like thermal cycling, vibration, or voltage spikes can degrade these components over time. In hybrid electric vehicles, the BMS relies on accurate data to perform functions such as state-of-charge estimation, thermal management, and cell balancing. The state-of-charge (SOC) for a battery in a hybrid electric vehicle can be estimated using formulas like:

$$ \text{SOC} = \frac{Q_{\text{remaining}}}{Q_{\text{total}}} \times 100\% $$

where \( Q_{\text{remaining}} \) is the remaining capacity and \( Q_{\text{total}} \) is the total capacity. Without precise voltage and temperature inputs, such calculations become erroneous, leading to operational faults. Additionally, temperature readings are crucial for safety; the relationship between resistance and temperature in sensors can be modeled as:

$$ R(T) = R_0 \left[1 + \alpha (T – T_0)\right] $$

where \( R(T) \) is resistance at temperature \( T \), \( R_0 \) is reference resistance at \( T_0 \), and \( \alpha \) is the temperature coefficient. In this case, the faulty chip reported -40 °C, a default error value, which triggered protective measures in the hybrid electric vehicle.

To resolve the fault, I replaced the damaged MAX17823B chip with a new one, ensuring proper soldering and alignment. After reassembly, I retested the collector’s signals: both transmit and receive pins on the MAX17841B showed normal waveforms, indicating restored communication. Upon reinstalling the module into the hybrid electric vehicle’s battery pack, I cleared the fault codes and reinitialized the BMS. Subsequent data streams displayed correct voltages and temperatures for all cells, and the high-voltage warning light extinguished. The hybrid electric vehicle was then able to operate in electric mode seamlessly, with the engine cycling appropriately and the low-voltage battery maintaining charge. This repair underscores the feasibility of component-level fixes in hybrid electric vehicles, which can be cost-effective compared to whole-module replacements.

The broader implications of this case extend to maintenance practices for hybrid electric vehicles. Regular diagnostics and proactive monitoring of high-voltage battery systems can prevent such faults. Below is a table summarizing common fault symptoms and their potential causes in hybrid electric vehicles:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inability to drive electrically | High-voltage contactor failure, BMS fault | Check contactor operation, scan for codes |

| Battery warning light illuminated | Cell imbalance, temperature sensor fault | Analyze data streams, measure cell voltages |

| Low-voltage battery depletion | DC/DC converter issues, parasitic drains | Test converter output, inspect circuits |

| Persistent engine operation | High-voltage system isolation faults | Verify isolation resistance, inspect relays |

In hybrid electric vehicles, the integration of high-voltage and low-voltage systems necessitates careful design. The DC/DC converter, which steps down high-voltage to charge the low-voltage battery, can be affected by high-voltage battery faults. Its efficiency \( \eta \) is given by:

$$ \eta = \frac{P_{\text{out}}}{P_{\text{in}}} \times 100\% $$

where \( P_{\text{out}} \) is output power and \( P_{\text{in}} \) is input power. When the high-voltage battery is faulty, input power may be limited, reducing converter output and leading to low-voltage battery drain—exactly as observed in this hybrid electric vehicle case.

Preventive maintenance for hybrid electric vehicles should include periodic checks of battery module voltages and temperatures. Using a standardized approach, technicians can log data over time to detect trends. For instance, the variance in cell voltages within a hybrid electric vehicle battery pack should be minimal; excessive variance \( \sigma^2 \) can be calculated as:

$$ \sigma^2 = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} (V_i – \bar{V})^2 $$

where \( V_i \) is the voltage of cell \( i \), \( \bar{V} \) is the average voltage, and \( N \) is the number of cells. Values beyond a threshold, say 0.1 V, may indicate impending faults. Additionally, thermal management is critical; the heat dissipation \( Q \) in a hybrid electric vehicle battery can be estimated using:

$$ Q = I^2 R t $$

where \( I \) is current, \( R \) is internal resistance, and \( t \) is time. Proper cooling ensures longevity and safety.

In conclusion, diagnosing high-voltage battery faults in hybrid electric vehicles demands a blend of theoretical knowledge and practical skills. This case study illustrates how a systematic process—from code reading and data analysis to circuit testing and component repair—can resolve complex issues. The hybrid electric vehicle ecosystem is evolving, with advancements in battery technology and management systems, but core principles remain. By sharing such experiences, I aim to contribute to the reliability and sustainability of hybrid electric vehicles. As more hybrid electric vehicles populate roads, technicians must stay adept at handling their unique challenges, ensuring these vehicles deliver on their promise of efficiency and environmental friendliness.

To further aid understanding, here is a table comparing key parameters of high-voltage batteries in various hybrid electric vehicle models:

| Hybrid Electric Vehicle Model | Battery Type | Nominal Voltage (V) | Capacity (kWh) | Common Fault Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plug-in Hybrid Sedan | Lithium-ion | 350 | 12 | Collector circuits, cell balancing |

| Full Hybrid SUV | Nickel-metal hydride | 288 | 1.5 | Temperature sensors, contactors |

| Mild Hybrid Compact | Lithium-polymer | 48 | 0.5 | DC/DC converters, wiring harnesses |

Ultimately, the hybrid electric vehicle represents a pinnacle of automotive innovation, and its maintenance is a rewarding field for those willing to delve into its complexities. Through continuous learning and hands-on experience, technicians can ensure that hybrid electric vehicles remain reliable and efficient for years to come.