In the context of global energy transition and the drive toward carbon neutrality, the electric vehicle industry has experienced explosive growth, with sales exceeding 12 million units in 2024 according to industry data. As a core component of electric vehicles, the high-voltage system directly impacts vehicle performance and safety. However, the EV repair sector faces significant challenges, including risks such as electric shock, arc burns, short circuits, and explosions during high-voltage system maintenance. Thus, specialized repair capabilities for high-voltage systems have become a critical demand in the electrical car repair industry. From my perspective as an educator in vocational training, I aim to address these issues by developing standardized safety operation strategies that cover key technical aspects like vehicle power-down, low-voltage disconnection, high-voltage verification, physical isolation, secondary testing, and energy locking. This approach seeks to provide a safety management paradigm for vocational education, helping schools and enterprises shorten talent cultivation cycles and reduce accident rates.

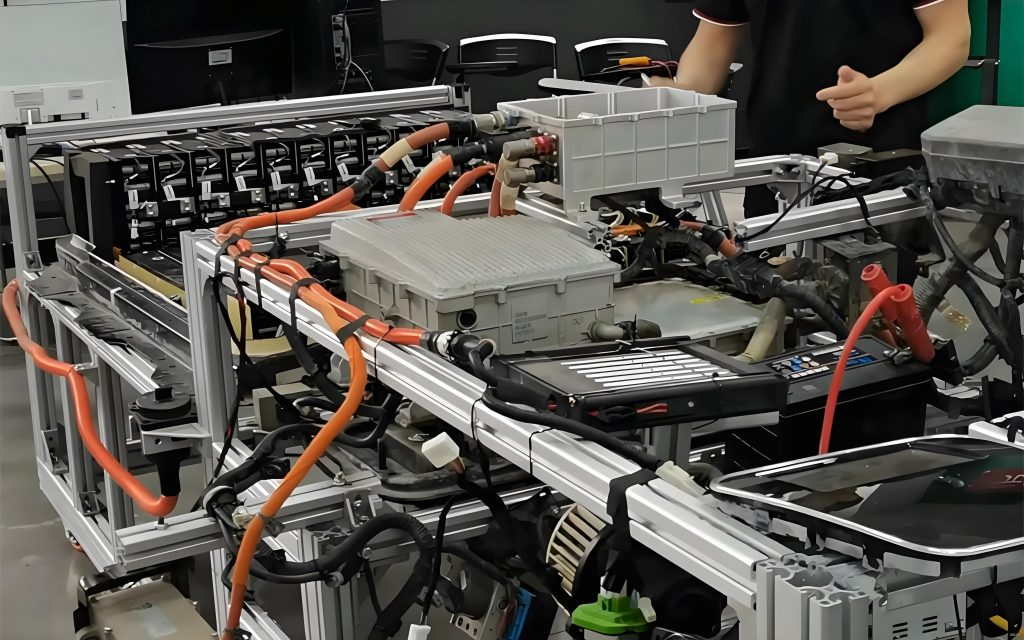

The high-voltage system in electric vehicles serves as the primary power core, comprising several key components that form a functional loop. To better illustrate this, I have summarized the main components and their functions in Table 1. This system is distinct from traditional internal combustion engines, as it relies on electrical energy conversion rather than mechanical drives.

| Component | Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Power Battery System | Stores energy and monitors real-time status | High energy density, with management systems for state of charge |

| Drive Motor and Controller | Converts electrical energy to mechanical energy for torque output | Efficiency up to $$ \eta_m = \frac{P_{\text{mech}}}{P_{\text{elec}}} \times 100\% $$, where $$ P_{\text{mech}} $$ is mechanical power and $$ P_{\text{elec}} $$ is electrical power |

| On-Board Charger | Converts external AC to high-voltage DC for charging, evolving toward bidirectional power flow | Power ratings typically from 3.3 kW to 22 kW, with efficiency factors |

| High-Voltage Distribution Unit | Acts as a power hub, controlling high-voltage distribution via contactors | Includes safety interlocks and fault detection |

| DC/DC Converter | Steps down high-voltage DC to 12 V/24 V for low-voltage systems | Efficiency defined as $$ \eta_{\text{DC/DC}} = \frac{V_{\text{out}} I_{\text{out}}}{V_{\text{in}} I_{\text{in}}} $$, with $$ V_{\text{in}} $$ up to 400 V |

| High-Voltage Cabling and Connectors | Ensures safe high-current transmission with IP67 or higher protection | Resistance per unit length $$ R = \rho \frac{L}{A} $$, where $$ \rho $$ is resistivity, L is length, A is cross-sectional area |

| High-Voltage Accessory System | Includes high-power loads like electric AC compressors and PTC heaters | Power consumption can be modeled as $$ P = V \times I $$ for thermal management |

In EV repair, understanding the common fault types is essential for effective maintenance. Based on my experience, high-voltage system faults can be categorized into several types, each with distinct causes and implications. Table 2 outlines these fault types, which often require systematic diagnostic approaches in electrical car repair to address compounded issues, such as insulation degradation leading to controller failures.

| Fault Type | Primary Causes | Potential Consequences |

|---|---|---|

| Insulation Faults | Physical damage to cables, seal failure, or aging | Reduced insulation resistance, risk of leakage or short circuits, with resistance $$ R_{\text{ins}} < 1\, \text{M}\Omega $$ indicating failure |

| Connection Faults | Loose connectors, poor contacts, or contact erosion | Increased contact resistance $$ R_c $$, leading to overheating and component damage; power loss can be estimated as $$ P_{\text{loss}} = I^2 R_c $$ |

| Power Battery System Faults | Cell degradation, overcharge/discharge, BMS malfunctions | Reduced range and safety hazards; state of health (SoH) can be modeled as $$ \text{SoH} = \frac{C_{\text{actual}}}{C_{\text{nominal}}} \times 100\% $$ |

| Drive Motor and Controller Faults | Winding insulation failure, semiconductor module breakdown, cooling leaks | Abnormal torque output or noise; efficiency drops as per $$ \eta_m $$ degradation |

| Charging System Faults | Converter failures, mechanical lock issues, communication protocol interruptions | Complete charging failure; power transfer efficiency $$ \eta_{\text{charge}} $$ may fall below thresholds |

The risks associated with high-voltage system maintenance in EV repair are multifaceted and require a comprehensive safety framework. From my analysis, these risks can be grouped into several categories, as detailed in Table 3. Each risk type demands specific preventive measures, such as using personal protective equipment (PPE) and adhering to strict protocols to mitigate hazards like electric shock or fire during electrical car repair operations.

| Risk Category | Description | Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|---|

| Electric Shock | Direct contact with live parts or residual charge after incomplete power-down | Ensure voltage $$ V < 60\, \text{V DC} $$ after disconnection; use insulated tools |

| Arc Burn | Short-circuit arcs from operational errors, generating instantaneous high temperatures | Follow safe disconnection sequences; arc energy can be estimated as $$ E_{\text{arc}} = V \times I \times t $$, where t is duration |

| Short Circuit | Improper tool use causing direct shorts between poles or to ground | Use designated insulated tools; short-circuit current $$ I_{\text{sc}} = \frac{V}{R_{\text{total}}} $$ should be limited by fuses |

| Chemical Risks | Leaks of battery electrolyte or coolant, posing corrosion or toxicity hazards | Handle chemicals with care; pH levels and containment are critical |

| Mechanical Risks | Injuries from handling heavy components or cable strain | Use proper lifting techniques; stress $$ \sigma = \frac{F}{A} $$ should be within safe limits |

| Fire and Explosion | Thermal runaway in batteries or electrical shorts leading to rapid fire spread | Implement fire suppression systems; monitor temperature $$ T $$ to prevent $$ T > T_{\text{critical}} $$ |

To address these risks, a standardized safety operation strategy is essential in EV repair. This strategy begins with thorough pre-repair preparations, which I categorize into three core areas: information, site, and personnel readiness. For information, technicians must obtain detailed vehicle schematics, repair manuals, and fault codes to identify risk points. Site preparation involves using dedicated insulated workstations with clearly marked tool areas to separate insulated from non-insulated tools. Personnel must wear full PPE, including double-layer insulated gloves (checked for integrity), face shields, insulated shoes, and flame-resistant clothing. Additionally, I recommend creating a “safety预案 card” to pre-assess potential risks like electric shock or short circuits and outline response measures. This proactive approach in electrical car repair minimizes accidents and enhances efficiency.

During the actual repair process, the standardized power-down procedure is the cornerstone of safety in high-voltage system maintenance. From my practice, this involves a step-by-step approach that must be strictly followed in EV repair to ensure all energy sources are isolated. The key steps include vehicle power-down, low-voltage disconnection, high-voltage verification, physical isolation, secondary testing, and energy locking. For instance, in the high-voltage verification step, technicians use a digital multimeter to measure voltages at critical points, ensuring they are below the safe threshold of $$ V < 60\, \text{V DC} $$. The voltage measurement can be expressed as $$ V_{\text{measure}} = \frac{P_{\text{residual}}}{I_{\text{leakage}}} $$ for residual power checks. Similarly, the waiting time for vehicle dormancy varies by model—for example, some require 10–20 minutes—and should never be shortened to prevent accidental activation. After physical isolation, a secondary verification is crucial to confirm the effectiveness of disconnection, using formulas like $$ V_{\text{final}} = 0 $$ for ideal conditions, but in practice, tolerances apply. Finally, energy locking involves securing the maintenance switch in an insulated box and implementing lockout-tagout procedures to prevent accidental re-energization. This comprehensive process in electrical car repair not only safeguards technicians but also aligns with industry standards, reducing the likelihood of incidents during EV repair tasks.

In conclusion, I have developed a standardized, full-process safety operation strategy for high-voltage systems in electric vehicles, focusing on mitigating core risks such as electric shock, arc burns, short circuits, chemical exposures, mechanical hazards, and fire or explosion. By emphasizing a “prevention-first, multiple-protection” principle, this strategy outlines a clear sequence: vehicle power-down → low-voltage disconnection → high-voltage verification → physical isolation → secondary testing → energy locking. Incorporating dual electrical verification and engineering controls, this approach effectively minimizes accidents in EV repair. Through continuous refinement and adherence to these protocols, the electrical car repair industry can enhance safety, improve training outcomes, and support the sustainable growth of electric mobility.