As a seasoned automotive technician specializing in hybrid electric vehicle systems, I have encountered numerous complex faults that test the limits of conventional diagnostics. The evolution of hybrid electric vehicle technology demands a deep understanding of both high-voltage and low-voltage networks, along with sophisticated control strategies. In this extensive article, I will delve into detailed repair narratives, emphasizing the intricate interplay of components in a hybrid electric vehicle. Through these cases, I aim to illustrate systematic approaches, leveraging tables and formulas to synthesize knowledge. The keyword ‘hybrid electric vehicle’ will be central, as these systems represent the forefront of automotive innovation.

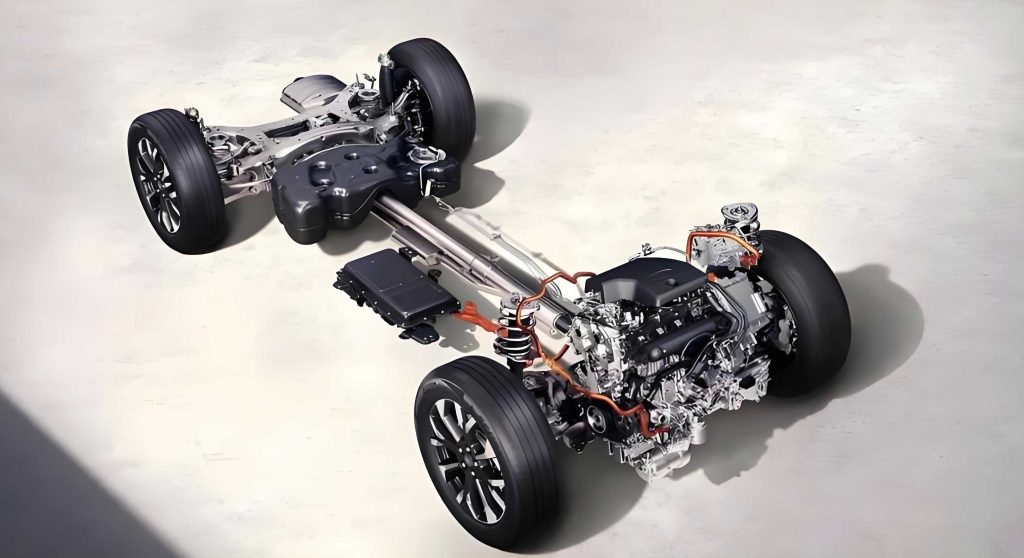

My journey with hybrid electric vehicle repairs often begins with understanding the core principles. A hybrid electric vehicle integrates an internal combustion engine with one or more electric motors, powered by a high-voltage battery pack. The energy management system, often termed the Hybrid Power Manager, governs the transition between driving modes. Key conditions must be met for electric-only propulsion, which can be summarized in the following table:

| System Parameter | Threshold for Electric Drive Mode | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Vehicle Speed (v) | $$v \leq 130 \text{ km/h}$$ | Kinetic energy limits for motor efficiency. |

| High-Voltage Battery State of Charge (SOC) | $$\text{SOC} \geq 34\%$$ | Ensures sufficient electrochemical energy reserve. |

| Battery Temperature (T) | $$T \geq -10^\circ \text{C}$$ | Prevents damage from low-temperature operation. |

| 12V Low-Voltage Network Health | Stable voltage ≥ 12V | Critical for control unit operation and safety interlocks. |

Failure to meet any single condition disables the electric drive mode, a common issue in hybrid electric vehicle diagnostics. The mathematical representation of the enable logic can be expressed as:

$$E_{\text{mode}} = \begin{cases}

\text{Enabled} & \text{if } (v \leq v_{\text{max}}) \land (\text{SOC} \geq \text{SOC}_{\text{min}}) \land (T \geq T_{\text{min}}) \land (V_{12V} \geq V_{\text{min}}) \\

\text{Disabled} & \text{otherwise}

\end{cases}$$

where \(E_{\text{mode}}\) is the electric drive mode status, \(v_{\text{max}} = 130 \text{ km/h}\), \(\text{SOC}_{\text{min}} = 0.34\), \(T_{\text{min}} = -10^\circ \text{C}\), and \(V_{\text{min}} = 12 \text{ V}\). This formula encapsulates the Boolean logic implemented in the hybrid electric vehicle’s central controller.

In one notable instance, a hybrid electric vehicle was presented with the electric drive mode grayed out and unavailable. This is a classic symptom in a hybrid electric vehicle, often leading to extensive checks. Initial inspection revealed a depleted high-voltage battery, but connecting to an AC charging station resulted in a persistent red charging indicator. Consulting the hybrid electric vehicle’s charging system documentation, I referenced the indicator state table:

| Charging Indicator State | System Interpretation | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Green | Charging complete, target SOC reached. | Disconnect charger. |

| Flashing Green | Active charging in progress. | Monitor until solid. |

| Solid Yellow | Charger detected but no grid power. | Check external power source. |

| Flashing Yellow | Transmission not in Park. | Shift to P position. |

| Solid Red | Charging plug lock mechanism fault. | Re-seat plug or inspect lock. |

| Flashing Red | Temperature extreme or internal fault. | System diagnostic required. |

The solid red light pointed directly to a locking issue. Diagnostic trouble code (DTC) P33E800 further confirmed “Charging Socket A, Charging Plug Lock, Mechanical Fault.” Upon disassembling the charging port, I found the lock motor seized. This mechanical failure in the hybrid electric vehicle’s charging interface prevented high-voltage battery replenishment, thus violating the SOC condition for electric drive. Bypassing the lock manually allowed charging, but the electric mode remained inactive even after achieving full SOC—a twist highlighting the multi-faceted nature of hybrid electric vehicle faults.

Further scanning revealed DTCs U04470 and C11CB01 in the gateway and engine control modules, related to data bus and 12V system faults. This redirected focus to the low-voltage network, a common culprit in hybrid electric vehicle malfunctions. The 12V system in a hybrid electric vehicle is not merely for lighting; it powers critical control units and safety relays. Its health is paramount. The vehicle employed a dual-battery setup: a main battery (A) and a backup battery (A1), designed to ensure starter motor engagement during engine starts. The circuit operation can be modeled using Kirchhoff’s voltage law. When the starter is activated, the system isolates the main battery for the starter solenoid and motor, while the backup battery supplies the rest of the network. The voltage relationship during cranking can be approximated as:

$$V_{\text{starter}} = V_{\text{A}} – I_{\text{starter}} \cdot R_{\text{cable}}$$

$$V_{\text{network}} = V_{\text{A1}} – I_{\text{load}} \cdot R_{\text{isolator}}$$

where \(V_{\text{A}}\) and \(V_{\text{A1}}\) are the open-circuit voltages of the main and backup batteries, respectively, \(I\) represents currents, and \(R\) denotes resistances in the paths.

Measuring voltages with the engine off showed the main battery at a normal 12.0V, but the backup battery plummeted to 6.0V, indicating severe capacity loss or internal short. The backup battery’s failure meant the low-voltage network integrity was compromised during system checks, causing the hybrid manager to inhibit electric drive as a safety measure. This aligns with the formula for \(E_{\text{mode}}\), where the \(V_{12V} \geq V_{\text{min}}\) condition failed intermittently. Replacing the backup battery and repairing the charging lock resolved both issues, restoring full functionality to the hybrid electric vehicle.

Another fascinating case involved a hybrid electric vehicle with intermittent electrical glitches, such as random door ajar warnings and illumination flickers. These symptoms often stem from wiring integrity issues, which are magnified in a hybrid electric vehicle due to complex wire routing alongside high-voltage cables. The customer reported issues worsening over months, particularly after rain or car washes. This pointed to water ingress causing sporadic short circuits.

Diagnosis involved methodically testing each door control module. Using a multimeter, I measured resistance between the door lock signal wire and ground. A normal reading should be high (e.g., >10 kΩ), but in this hybrid electric vehicle, the right rear door lock circuit showed intermittent near-zero resistance when the door was agitated. The fault was traced to the lock wire harness being pinched by a window regulator mounting bolt during original assembly—a manufacturing oversight. Water accumulation completed the short circuit path, sending false door-open signals to the Body Control Module (BCM).

To generalize, such wiring faults can be analyzed using the current-division principle. When a short to ground occurs, the current \(I_{\text{fault}}\) diverts from the intended load, causing a voltage drop. The BCM interprets this drop as a state change. The relationship is:

$$V_{\text{sensed}} = V_{\text{supply}} – I_{\text{fault}} \cdot R_{\text{wire}}$$

where \(V_{\text{sensed}}\) falls below the logic-low threshold, triggering an erroneous signal.

Repairing the damaged wire and sealing the harness restored normal operation. This case underscores the importance of meticulous inspection in hybrid electric vehicle repairs, as even minor assembly errors can lead to persistent faults.

Expanding on diagnostic methodologies, I often employ a structured table to evaluate hybrid electric vehicle power mode failures:

| Subsystem | Key Checks | Measurement/Data Point | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Voltage Battery | State of Charge, Temperature, Isolation Resistance | SOC via scan tool, $$R_{\text{iso}} > 1 \text{ M}\Omega$$ | SOC > 34%, T > -10°C, No DTCs |

| Charging System | Plug Lock Mechanism, Pilot Signal, Contactor Engagement | Lock motor resistance, CP/PP signal voltage | Motor operable, Signals per ISO 15118 |

| 12V Low-Voltage System | Battery Voltage Under Load, Backup Battery Health, DC/DC Converter Output | $$V_{\text{load}} = V_{\text{oc}} – I \cdot R_{\text{internal}}$$ | Stable 13.5-14.5V engine running, >11.8V off |

| Control Network | CAN Bus Integrity, Gateway Module Communication | Bus terminal resistances (typically 60Ω), Message frequency | No bus-off errors, All nodes alive |

| Mechanical Integrity | Wiring Harness Routing, Connector Seals, Ground Points | Continuity tests, Visual inspection for pinch points | No damage, Corrosion, or Interference |

The DC/DC converter in a hybrid electric vehicle, which steps down high-voltage to charge the 12V system, is vital. Its efficiency \(\eta\) can be calculated from input and output power:

$$\eta = \frac{P_{\text{out}}}{P_{\text{in}}} = \frac{V_{\text{out}} \cdot I_{\text{out}}}{V_{\text{in}} \cdot I_{\text{in}}} \times 100\%$$

Typically, \(\eta\) should exceed 90% for proper operation. A failing converter can starve the 12V network, leading to cascading faults in the hybrid electric vehicle.

Furthermore, the hybrid electric vehicle’s regenerative braking system involves energy recovery calculations. The kinetic energy recovered during deceleration is:

$$E_{\text{regen}} = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} P_{\text{motor}}(t) \, dt = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \tau(t) \cdot \omega(t) \, dt$$

where \(\tau\) is motor torque and \(\omega\) is angular velocity. This energy replenishes the high-voltage battery, impacting SOC and drive mode availability.

In-depth analysis of fault codes is crucial. For instance, the code C11CB01 (“12V Electrical System Fault”) often correlates with backup battery degradation. The backup battery’s capacity \(C\) (in Ah) decays over time due to internal chemical reactions, modeled approximately by:

$$C(t) = C_0 \cdot e^{-\lambda t}$$

where \(C_0\) is initial capacity and \(\lambda\) is a decay constant. When \(C(t)\) falls below a threshold, voltage under load drops precipitously, triggering faults.

To prevent misdiagnosis, I verify sensor readings against physical measurements. For example, the battery sensor’s reported voltage should match multimeter readings within 0.1V. Discrepancies indicate sensor or wiring issues in the hybrid electric vehicle.

Another aspect is software calibration. Hybrid electric vehicle control units receive periodic updates. Incompatibilities can cause mode selection problems. Ensuring all modules are at recommended software levels is part of standard protocol.

Let’s consider thermal management, critical for hybrid electric vehicle battery longevity. The battery temperature rise during charging can be estimated using:

$$\Delta T = \frac{I_{\text{charge}}^2 \cdot R_{\text{internal}} \cdot t}{m \cdot c}$$

where \(m\) is battery mass, \(c\) is specific heat capacity, and \(t\) is time. Excessive \(\Delta T\) can trigger protection modes, disabling charging or electric drive.

Summarizing common failure modes in hybrid electric vehicles, I’ve compiled this table based on statistical data from my workshop:

| Failure Category | Frequency in Hybrid Electric Vehicle | Typical Symptoms | Root Cause Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12V Auxiliary System | High (≈40%) | Electric mode unavailable, Warning lights, Intermittent electronics | Backup battery failure, DC/DC converter fault, Corroded grounds |

| Charging Infrastructure | Medium (≈25%) | Unable to charge, Indicator anomalies, Reduced electric range | Lock motor failure, Pilot circuit faults, Connector damage |

| High-Voltage Battery | Low (≈15%) but severe | Drastic range loss, Thermal warnings, Isolation faults | Cell imbalance, Coolant leaks, BMS software errors |

| Wiring & Connectors | Medium (≈20%) | Intermittent errors, Unexplained signals, Water-related issues | Pinched harnesses, Seal degradation, Vibration fatigue |

Preventive maintenance for a hybrid electric vehicle includes regular checks of the 12V battery health using conductance testers, which measure conductance \(G\) related to internal resistance \(R_{\text{int}}\) by $$G = \frac{1}{R_{\text{int}}}$$. A declining \(G\) indicates aging.

In conclusion, diagnosing a hybrid electric vehicle requires a holistic approach, blending traditional automotive skills with expertise in high-voltage systems and network communications. The interplay between high-voltage and low-voltage domains is unique to hybrid electric vehicle architecture. By applying systematic checks, utilizing formulas to model system behavior, and referencing comprehensive tables, technicians can efficiently resolve even the most elusive faults. Every hybrid electric vehicle repair enhances our understanding of this transformative technology, paving the way for more reliable and sustainable mobility.

Finally, continuous learning is essential. As hybrid electric vehicle technology evolves, so do diagnostic techniques. Engaging with technical service bulletins, participating in specialist training, and sharing case studies like these fortify our ability to keep these advanced vehicles on the road. The hybrid electric vehicle is not just a car; it’s a complex system where every component, from a tiny lock motor to a massive battery pack, plays a critical role in delivering efficiency and performance.