In the development of hybrid electric vehicles, the battery management system (BMS) plays a critical role in ensuring safety, efficiency, and longevity of the energy storage system. As hybrid electric vehicles become more prevalent globally, driven by strategic initiatives like the “three verticals and three horizontals” plan in some regions, the complexity of BMS design has increased significantly. This complexity arises from the need to monitor numerous battery parameters, manage thermal conditions, and coordinate with other vehicle systems. To address these challenges, I have developed a comprehensive hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) testing system based on the RT-LAB platform. This system enables rapid, accurate, and thorough validation of BMS performance, control logic, and interaction with the hybrid electric vehicle environment, ultimately reducing development time and costs. In this article, I will detail the design, implementation, and experimental results of this HIL system, emphasizing its application in hybrid electric vehicle contexts.

The core motivation behind this work stems from the growing demand for reliable BMS solutions in hybrid electric vehicles. Traditional testing methods, such as physical prototyping and field trials, are often time-consuming, expensive, and limited in their ability to simulate extreme or fault conditions. HIL testing offers a viable alternative by combining real-time simulation models with physical hardware, allowing for iterative testing in a controlled environment. My system leverages RT-LAB, a powerful real-time simulation platform, to create a high-fidelity virtual representation of a hybrid electric vehicle, including its battery pack, powertrain, and dynamics. This approach not only accelerates the BMS development cycle but also enhances safety by enabling tests that would be hazardous in real-world scenarios. Throughout this discussion, I will focus on how this system caters specifically to hybrid electric vehicles, a key segment in the automotive industry’s shift towards electrification.

To begin, let me outline the overall architecture of the HIL testing system. It consists of both hardware and software components: the hardware includes a real-time simulator, battery simulators, fault injection devices, and the BMS unit under test, while the software encompasses real-time models of the battery and vehicle, the RT-LAB simulation environment, and a graphical interface for monitoring and automation. The system operates in a closed-loop manner, where the real-time model generates signals that are sent to the BMS via hardware interfaces, and the BMS responses are fed back into the model. This setup allows for comprehensive testing of BMS functionalities, such as state-of-charge (SOC) estimation, voltage and temperature monitoring, fault detection, and communication with other vehicle controllers. For hybrid electric vehicles, which often involve complex power-split strategies and frequent charge-discharge cycles, such testing is indispensable. I designed this system with modularity in mind, ensuring it can be adapted to various hybrid electric vehicle configurations, from mild hybrids to plug-in hybrids.

One of the foundational elements of the HIL system is the real-time simulation model. I developed this model using MATLAB/Simulink, with a focus on accurately representing the behavior of lithium-ion batteries and the hybrid electric vehicle powertrain. The battery model is based on a second-order RC equivalent circuit, which captures dynamic effects like polarization and internal resistance. This model is crucial for hybrid electric vehicles, as batteries undergo rapid charge and discharge during regenerative braking and acceleration. The model parameters, such as open-circuit voltage, series resistance, and polarization capacitances, are functions of SOC and temperature, derived from experimental data. I used lookup tables with interpolation to handle these nonlinearities, ensuring real-time performance. The equations governing the battery model are as follows:

$$V_{bat} = V_{oc}(SOC, T) – I \cdot R_{s}(SOC, T) – V_{1} – V_{2}$$

where $V_{bat}$ is the terminal voltage, $V_{oc}$ is the open-circuit voltage, $I$ is the current, $R_{s}$ is the series resistance, and $V_{1}$ and $V_{2}$ are voltages across RC networks representing polarization effects. The dynamics of $V_{1}$ and $V_{2}$ are described by:

$$\frac{dV_{1}}{dt} = \frac{I}{C_{1}(SOC, T)} – \frac{V_{1}}{R_{1}(SOC, T) \cdot C_{1}(SOC, T)}$$

$$\frac{dV_{2}}{dt} = \frac{I}{C_{2}(SOC, T)} – \frac{V_{2}}{R_{2}(SOC, T) \cdot C_{2}(SOC, T)}$$

Here, $R_{1}$, $C_{1}$, $R_{2}$, and $C_{2}$ are polarization resistances and capacitances, all dependent on SOC and temperature $T$. To parameterize this model, I conducted experiments on a 60 Ah lithium iron phosphate battery, typical for hybrid electric vehicles, and used nonlinear least-squares fitting. The resulting parameter tables enable the model to simulate battery behavior across diverse operating conditions encountered in hybrid electric vehicles.

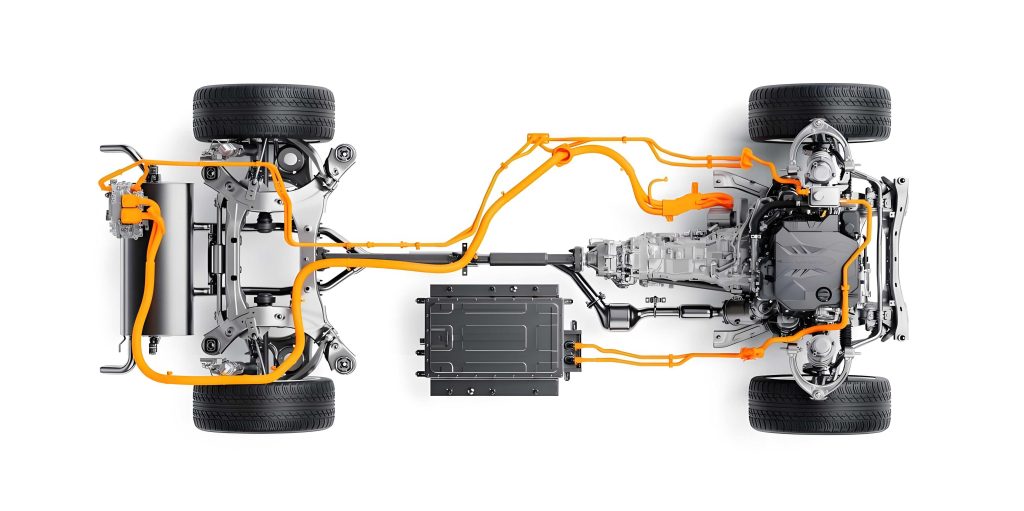

The vehicle model for the hybrid electric vehicle includes sub-models for the driver, engine, electric motors, transmission, tires, and vehicle dynamics. I implemented a power-split hybrid architecture, common in many hybrid electric vehicles, which allows both series and parallel operating modes. In series mode, the engine drives a generator to charge the battery, while the vehicle is propelled solely by an electric motor. In parallel mode, the engine and motor can jointly drive the wheels, enabling modes like pure electric drive, hybrid drive, and regenerative charging. This flexibility is essential for testing BMS strategies under different driving scenarios. The vehicle dynamics are governed by:

$$F_{trac} = F_{aero} + F_{roll} + F_{grade} + m \cdot a$$

where $F_{trac}$ is the traction force, $F_{aero}$ is aerodynamic drag, $F_{roll}$ is rolling resistance, $F_{grade}$ is grade resistance, $m$ is vehicle mass, and $a$ is acceleration. The powertrain model calculates torque and speed based on driver inputs and energy management strategies. For real-time execution, I optimized the model using RT-LAB’s multi-core processing capabilities, which partition the Simulink model across CPU cores for parallel computation. This ensures that the model runs synchronously with real-time, a prerequisite for HIL testing. The integration of these models provides a virtual environment that mimics the hybrid electric vehicle’s behavior, allowing the BMS to be tested as if it were installed in an actual vehicle.

To support the real-time model, the hardware setup is designed to interface seamlessly with the BMS. The core hardware includes a real-time simulator (e.g., OPAL-RT series), battery simulator units, a high-voltage loop simulation box, fault injection equipment, and various I/O boards. The battery simulator is a custom-built device capable of simulating up to 120 battery cells in series or parallel configurations, each with programmable voltage (0-5 V) and internal resistance. This is vital for hybrid electric vehicles, where battery packs often consist of numerous cells requiring precise monitoring. The simulator channels are isolated to prevent cross-talk and can simulate faults like open or short circuits. The high-voltage loop simulation box replicates the vehicle’s high-voltage bus, typically ranging from 200 V to 400 V in hybrid electric vehicles. It includes relays and capacitors to emulate pre-charge sequences and fault conditions such as insulation failures. This box allows testing of BMS high-voltage measurement and safety functions. Additionally, fault injection devices enable deliberate introduction of sensor failures, communication errors, and other anomalies to validate BMS robustness. The I/O boards handle analog and digital signals, including CAN communication, which is standard in hybrid electric vehicles for inter-controller data exchange. A summary of key hardware specifications is provided in Table 1.

| Component | Specification | Role in Hybrid Electric Vehicle Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Real-Time Simulator | Multi-core CPU, real-time OS, analog/digital I/O | Executes vehicle and battery models in real-time |

| Battery Simulator | 120 channels, 0-5 V per channel, isolated outputs | Simulates individual cell voltages for BMS monitoring |

| High-Voltage Simulation Box | Up to 500 V, programmable pre-charge circuits | Tests BMS high-voltage sensing and safety protocols |

| Fault Injection Unit | Programmable switches for sensor and line faults | Validates BMS fault detection and handling in hybrid electric vehicles |

| CAN Interface Board | Supports CAN 2.0 A/B, multiple channels | Facilitates communication simulation with other vehicle ECUs |

The software aspect of the system revolves around RT-LAB for real-time simulation and a graphical interface built with PROVEtech:TA software. RT-LAB compiles the Simulink model into real-time code and downloads it to the simulator, ensuring deterministic execution with step sizes as low as 50 microseconds. This precision is necessary for capturing fast transients in hybrid electric vehicle operations, such as sudden acceleration or regenerative braking. The PROVEtech:TA interface provides a user-friendly dashboard for configuring tests, monitoring parameters, and automating sequences. I designed this interface to include widgets for voltage, current, temperature, SOC display, fault injection controls, and CAN message analysis. For hybrid electric vehicle testing, specific driving cycles like urban, highway, or aggressive acceleration can be loaded to simulate realistic conditions. The automation feature allows scripted test sequences to run unattended, saving time during repetitive validation tasks. For instance, I created scripts to cycle through different SOC levels and temperatures while checking BMS responses, which is crucial for hybrid electric vehicles that experience varying load profiles.

Experiments conducted with this HIL system demonstrate its effectiveness in validating BMS for hybrid electric vehicles. I performed tests in three categories: specification verification, functional testing, and logic testing under various driving conditions. Specification tests involve checking BMS measurement accuracy for voltage, current, and temperature against known inputs from the simulator. Functional tests assess features like cell balancing, overcharge protection, and communication protocols. Logic tests evaluate the BMS control strategies during simulated driving scenarios, such as acceleration, braking, and mode transitions. To illustrate, I ran a simulation of a hybrid electric vehicle accelerating from 0 to 150 km/h over 23 seconds, followed by steady cruising. The battery model outputted voltage and SOC trends that matched theoretical expectations. During acceleration, the SOC decreased from 79.6% to 78.15%, and the pack voltage dropped due to high discharge currents, with fluctuations corresponding to gear shifts. The temperature rose slightly from 20°C to 21.9°C. These results are consistent with real-world behavior in hybrid electric vehicles, confirming the model’s fidelity. Similarly, a braking simulation showed SOC recovery due to regenerative charging, with voltage rising and then stabilizing. Table 2 summarizes key results from these tests.

| Test Scenario | Parameter | Initial Value | Final Value | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acceleration (0-150 km/h) | SOC | 79.6% | 78.15% | Linear decrease due to discharge |

| Acceleration (0-150 km/h) | Pack Voltage | 380 V | ~340 V (min) | Voltage sag under high current |

| Braking (150-0 km/h) | SOC | 77.08% | 77.26% | Increase from regenerative charging |

| Braking (150-0 km/h) | Pack Voltage | ~340 V | ~380 V | Voltage rise during energy recovery |

| Fault Injection | Cell Overvoltage | Normal | Fault Triggered | BMS correctly detected and logged fault |

In addition to dynamic tests, I evaluated the BMS performance under fault conditions, which is critical for safety in hybrid electric vehicles. Using the fault injection unit, I simulated cell voltage imbalances, sensor disconnections, and CAN communication errors. The BMS successfully identified these faults and took appropriate actions, such as alerting the driver or isolating the battery pack. This capability is vital for hybrid electric vehicles, where electrical faults can lead to hazardous situations. The HIL system also allowed for stress testing by running extended driving cycles, such as the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), to assess BMS endurance and thermal management. During these tests, the model’s thermal sub-model predicted temperature changes based on ambient conditions and current flow, enabling validation of BMS cooling strategies. The integration of these diverse test scenarios underscores the system’s comprehensiveness for hybrid electric vehicle applications.

From a mathematical perspective, the accuracy of the battery model is paramount. I validated the model by comparing simulation outputs with experimental data from pulse discharge tests on a 60 Ah battery. The results showed a maximum voltage error of only 4.5 mV, demonstrating high precision. This validation process involved solving the differential equations of the RC model using numerical methods like forward Euler, implemented in Simulink for real-time execution. The discretized form for real-time simulation is:

$$V_{1}[k+1] = V_{1}[k] + \Delta t \cdot \left( \frac{I[k]}{C_{1}[k]} – \frac{V_{1}[k]}{R_{1}[k] \cdot C_{1}[k]} \right)$$

$$V_{2}[k+1] = V_{2}[k] + \Delta t \cdot \left( \frac{I[k]}{C_{2}[k]} – \frac{V_{2}[k]}{R_{2}[k] \cdot C_{2}[k]} \right)$$

where $k$ is the time step index and $\Delta t$ is the sampling time. This discretization ensures stability and real-time feasibility. For hybrid electric vehicles, where battery states change rapidly, such accurate modeling is essential to test BMS algorithms like SOC estimation. I implemented an extended Kalman filter (EKF) in the BMS software and used the HIL system to tune its parameters. The EKF equations are:

$$\hat{x}_{k|k-1} = f(\hat{x}_{k-1|k-1}, u_{k-1})$$

$$P_{k|k-1} = F_{k-1} P_{k-1|k-1} F_{k-1}^T + Q_{k-1}$$

$$K_k = P_{k|k-1} H_k^T (H_k P_{k|k-1} H_k^T + R_k)^{-1}$$

$$\hat{x}_{k|k} = \hat{x}_{k|k-1} + K_k (z_k – h(\hat{x}_{k|k-1}))$$

$$P_{k|k} = (I – K_k H_k) P_{k|k-1}$$

where $\hat{x}$ is the state vector (e.g., SOC, $V_1$, $V_2$), $u$ is input current, $z$ is measured voltage, $f$ and $h$ are nonlinear functions from the battery model, $F$ and $H$ are Jacobian matrices, $Q$ and $R$ are covariance matrices, and $K$ is the Kalman gain. By injecting simulated sensor noise via the HIL system, I optimized $Q$ and $R$ to achieve SOC estimation errors below 2% in hybrid electric vehicle driving cycles. This level of accuracy is crucial for reliable range prediction and energy management in hybrid electric vehicles.

The scalability of the HIL system is another advantage for hybrid electric vehicle development. It can be adapted to different battery chemistries (e.g., lithium-ion, nickel-metal hydride) and vehicle architectures (e.g., series, parallel, or complex power-split hybrids). I achieved this by parameterizing the models and hardware configurations through configuration files. For instance, to test a BMS for a plug-in hybrid electric vehicle with a larger battery capacity, I simply updated the battery model parameters and increased the number of simulator channels. This flexibility reduces the need for multiple physical prototypes, saving costs. Moreover, the system supports integration with other vehicle controllers, such as the engine control unit (ECU) and motor controller, via CAN simulation. This allows testing the BMS in a network environment, reflecting the interconnected nature of hybrid electric vehicle systems. I conducted tests where the BMS communicated with a simulated ECU to request engine start-stop based on SOC, verifying coordination strategies.

Looking ahead, this HIL testing system can be enhanced with more advanced features for hybrid electric vehicles. For example, incorporating machine learning algorithms for battery health prediction or adding hardware for thermal chamber integration to simulate extreme temperatures. The real-time models could also be extended to include aging effects, which are significant in hybrid electric vehicles due to frequent cycling. From a practical standpoint, the system has already been used in the development of BMS for several hybrid electric vehicle projects, demonstrating reductions in testing time by over 50% compared to traditional methods. This efficiency stems from the ability to automate tests, replicate scenarios precisely, and safely evaluate fault conditions. As hybrid electric vehicles evolve towards higher voltage levels and faster charging, such testing systems will become even more indispensable.

In conclusion, the hardware-in-the-loop testing system based on RT-LAB provides a robust platform for developing and validating battery management systems in hybrid electric vehicles. By combining high-fidelity real-time models with flexible hardware interfaces, it enables comprehensive testing of BMS performance under diverse conditions. The system’s accuracy, demonstrated through experimental results, ensures that BMS designs meet the stringent requirements of hybrid electric vehicles. Furthermore, its modularity and automation capabilities streamline the development process, reducing time-to-market and costs. As the automotive industry continues to embrace electrification, tools like this HIL system will play a pivotal role in advancing hybrid electric vehicle technology. I believe that continued refinement of such systems, coupled with collaboration across industry and academia, will drive innovation in BMS for hybrid electric vehicles, ultimately leading to safer, more efficient, and more reliable vehicles on the road.

To reiterate, the key takeaway is that this HIL system offers a holistic solution for BMS testing in hybrid electric vehicles. It addresses challenges specific to hybrid electric vehicles, such as dynamic power flows and complex powertrain interactions. By leveraging real-time simulation and hardware integration, it bridges the gap between virtual design and physical deployment. I encourage further exploration of HIL methodologies in the context of hybrid electric vehicles, as they hold great promise for accelerating the transition to sustainable transportation. In my future work, I plan to extend this system to support vehicle-to-grid (V2G) testing for hybrid electric vehicles, exploring new frontiers in energy management. Through such efforts, we can unlock the full potential of hybrid electric vehicles in a rapidly evolving automotive landscape.