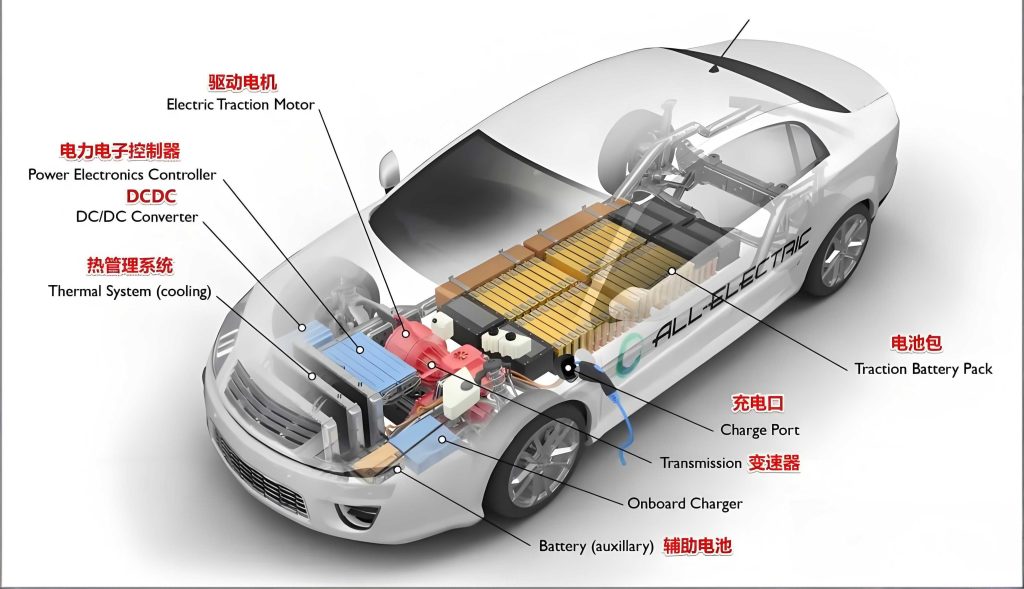

In the rapidly evolving landscape of the automotive industry, the rise of the battery electric car represents a pivotal shift towards sustainable transportation. As a key component, the battery pack serves as the heart of any battery electric car, storing the energy required for propulsion. Its structural integrity and sealing performance are paramount, directly influencing vehicle safety, range, and longevity. The battery pack enclosure, often fabricated from lightweight aluminum alloys, must provide robust protection against environmental ingress, such as water and dust, while efficiently managing thermal loads. Among various joining techniques, Friction Stir Welding (FSW) has emerged as a preferred method for assembling these enclosures due to its solid-state nature, which minimizes distortion and defects common in fusion welding. However, during mass production of battery packs for battery electric cars, occasional leakage failures in FSW joints pose significant reliability challenges. This study delves into a systematic investigation of such a leakage fault in the lower tray of a battery pack destined for a battery electric car, employing a first-person perspective to detail the analysis process, root cause identification, and subsequent process optimization.

The battery electric car market demands enclosures that are not only lightweight but also hermetically sealed to safeguard sensitive battery cells and cooling systems. The lower tray of the battery pack analyzed here is constructed from 6005-T6 aluminum alloy extrusions, chosen for its favorable strength-to-weight ratio and corrosion resistance. Its chemical composition and mechanical properties are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. These properties are critical as they form the baseline for evaluating weld integrity. The tray assembly comprises multiple components: two central floor panels, front and rear panels forming the liquid cooling plate, and left/right side panels. All joints are made via FSW, creating a complex network of seams that must be leak-tight to prevent coolant escape or external contamination—a failure that could compromise the entire battery electric car’s thermal management and safety.

| Mg | Si | Fe | Cu | Zn | Cr | Ti | Mn | Al |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.15 | 0.1 | 0.03 | 0.15 | Bal. |

| Material | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Yield Strength (MPa) | Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6005-T6 | 285 | 230 | 16 |

The FSW process was conducted using a stationary gantry-type 2D production machine, capable of welding aluminum sheets up to 8 mm thick. A split-design tool was employed, featuring a threaded and tri-flat pin with a length of 2.5 mm and a concave shoulder 10 mm in diameter. This tool design allows for cost-effective replacement of worn modules. Initial welding parameters included a rotational speed of 1200 rpm and a travel speed of 600 mm/min, which were derived from standard practices for aluminum alloys in battery electric car applications. However, during routine quality checks, a leakage failure was detected in a batch of battery packs, prompting a detailed failure analysis. The methodology I adopted involved a multi-step approach: first, replicating the leak via helium leak testing to locate the fault; second, conducting macro- and micro-structural examinations using optical microscopy (OM); and third, correlating the findings with process variables to deduce the root cause.

Helium leak testing, a sensitive method for detecting minute leaks, was performed on the faulty battery pack. The system was evacuated and pressurized with helium to 0.5 MPa, with a leak rate threshold set at ≤4.3 × 10⁻⁷ Pa·m³/s. The test confirmed a significant leak, as the pressure could not be maintained, and further inspection localized the leak to a specific FSW seam on the backside of the tray. Macroscopic observation of the leak site revealed a continuous, linear feature along the weld direction, resembling a crack. This was the suspected leakage path. To investigate further, I sectioned samples across this feature, prepared them metallographically by mounting, grinding, polishing, and etching with Keller’s reagent, and examined them under an optical microscope.

The microstructural analysis unveiled two distinct defects. The primary defect was a continuous, crack-like void extending from the faying surface to the weld crown. Crucially, this defect coincided with the original joint interface, which appeared merely bent and displaced rather than metallurgically bonded. This is characteristic of a “cold weld” or lack-of-penetration defect in FSW, where insufficient material flow and intermixing occur. The secondary defect consisted of porosity within the weld nugget, later attributed to a subsequent Tungsten Inert Gas (TIG) repair weld and not the direct cause of leakage. The cold weld defect’s morphology suggested that during FSW, the stirring pin was severely offset from the joint line, failing to plasticize and consolidate the interface material adequately. This misalignment created a weak, unbonded zone that acted as a conduit for fluid passage. The presence of such defects in a battery electric car pack is unacceptable, as it jeopardizes the sealing integrity of the cooling system.

To understand the formation mechanism, consider the FSW process dynamics. The heat input and material flow are governed by tool geometry, rotational speed (ω), and travel speed (v). A simplified model for heat generation (Q) during FSW can be expressed as:

$$ Q = \frac{2}{3} \pi \mu P \omega R^3 $$

where μ is the coefficient of friction, P is the axial pressure, and R is the shoulder radius. Inadequate heat input or improper tool alignment can lead to insufficient material plasticity, resulting in cold welds. Specifically, when the pin is offset from the joint line by a distance δ, the material on one side may not be adequately stirred. If δ exceeds a critical value, the interface remains unbonded. For the 2.5 mm thick 6005-T6 alloy in this battery electric car pack, the allowable offset is typically very small. My measurements indicated that the misalignment in the faulty weld was significant, likely exceeding 0.5 mm, which explains the defect.

The root cause was thus identified as a misalignment-induced cold weld defect. To address this, I proposed and implemented a process optimization centered on improving tool alignment precision. A laser tracking system was integrated into the FSW setup to monitor and correct the pin position in real-time, ensuring alignment within ±0.2 mm of the joint line. Additionally, welding parameters were refined through iterative trials. The optimized parameters are summarized in Table 3, alongside the initial settings for comparison.

| Parameter | Initial Value | Optimized Value |

|---|---|---|

| Rotational Speed (rpm) | 1200 | 1500 |

| Travel Speed (mm/min) | 600 | 800 |

| Pin Alignment Tolerance (mm) | Uncontrolled (± >0.5) | Controlled (±0.2) |

| Axial Force (kN) | 8 | 9 |

The optimization aimed to balance heat input and material flow. Higher rotational speed increases frictional heating, while higher travel speed reduces heat exposure, preventing excessive softening. The relationship can be described by the heat input per unit length (H):

$$ H = \frac{Q}{v} = \frac{ \frac{2}{3} \pi \mu P \omega R^3 }{ v } $$

For the optimized parameters, H is calculated to ensure sufficient plasticity without causing defects. After implementing these changes, I conducted metallographic examination on new weld samples. The results showed complete elimination of the cold weld defect, with a fully consolidated nugget and no visible discontinuities. Furthermore, helium leak tests on a batch of 500 battery packs produced with the optimized process demonstrated a dramatic improvement. The leak rate data is summarized in Table 4.

| Batch | Number of Packs | Leakage Failures | Pass Rate (%) | Average Leak Rate (Pa·m³/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Optimization | 100 | 15 | 85.0 | 2.1 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Post-Optimization | 500 | 1 | 99.8 | <4.3 × 10⁻⁷ |

The mechanical performance of the optimized welds was also evaluated. Tensile test specimens were extracted transverse to the weld direction, as per the schematic in the methodology. Five tests were conducted, and the average tensile strength was 209 MPa, which is approximately 73.5% of the base material strength (285 MPa). This meets the typical requirement for FSW joints in battery electric car applications, where joint efficiency above 70% is often acceptable. The strength can be modeled using a rule-of-mixtures approximation for the weld zone:

$$ \sigma_{weld} = f_{NZ} \cdot \sigma_{NZ} + f_{TMAZ} \cdot \sigma_{TMAZ} + f_{HAZ} \cdot \sigma_{HAZ} $$

where σ represents strength and f the area fraction of different zones: Nugget Zone (NZ), Thermo-Mechanically Affected Zone (TMAZ), and Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ). For the optimized weld, the high integrity of the NZ contributes dominantly to the overall strength. Fracture surface analysis via Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) revealed a dimpled morphology indicative of ductile fracture, confirming good toughness and absence of brittle failure modes.

Beyond the immediate fix, this analysis underscores broader implications for manufacturing battery packs for battery electric cars. FSW, while robust, is sensitive to process stability. In high-volume production, factors like fixture wear, thermal drift, and material lot variations can introduce alignment errors. The laser tracking system provides a proactive solution, but it is also essential to implement statistical process control (SPC) to monitor key parameters. For instance, control charts for tool offset (δ) and weld torque can be established. The torque (T) during FSW relates to material flow resistance and can be approximated as:

$$ T = k \cdot \mu \cdot P \cdot R^2 $$

where k is a geometric constant. Sudden changes in torque may signal alignment issues or material inhomogeneity. Integrating such real-time monitoring with automated feedback loops can further enhance reliability in producing battery electric car components.

Additionally, the choice of tool design plays a role. For critical joints in a battery electric car pack, where sealing is paramount, tools with slightly longer pins or active features that promote lateral material flow might be considered. However, any design change must be validated to avoid introducing new defects like excessive flash or root flaws. In this case, the existing tool geometry was adequate once alignment was controlled.

The economic impact of such quality improvements is substantial for battery electric car manufacturers. A single leakage failure in a battery pack can lead to costly recalls, warranty claims, and reputational damage. By reducing the leak rate from 15% to 0.2%, the optimized process not only enhances safety but also lowers production costs by minimizing rework and scrap. This aligns with the industry’s drive towards zero-defect manufacturing for critical components in battery electric cars.

In conclusion, this first-hand investigation into a leakage failure in a battery electric car pack’s FSW weld identified a cold weld defect caused by stirring pin misalignment as the root cause. Through the implementation of a laser tracking system for precise alignment control (±0.2 mm) and optimization of rotational speed to 1500 rpm and travel speed to 800 mm/min, the defect was eradicated. Batch validation confirmed a pass rate exceeding 99.8% in helium leak tests, with weld tensile strength achieving 73.5% of the base material. The findings highlight that meticulous control of tool alignment is critical for ensuring leak-tight joints in FSW assemblies for battery electric cars. Future work could explore advanced sensing techniques, such as force or acoustic emission monitoring, to further fortify quality assurance in the mass production of battery electric car packs. As the adoption of battery electric cars accelerates globally, robust and reliable welding methodologies will remain a cornerstone of safe and efficient vehicle design.