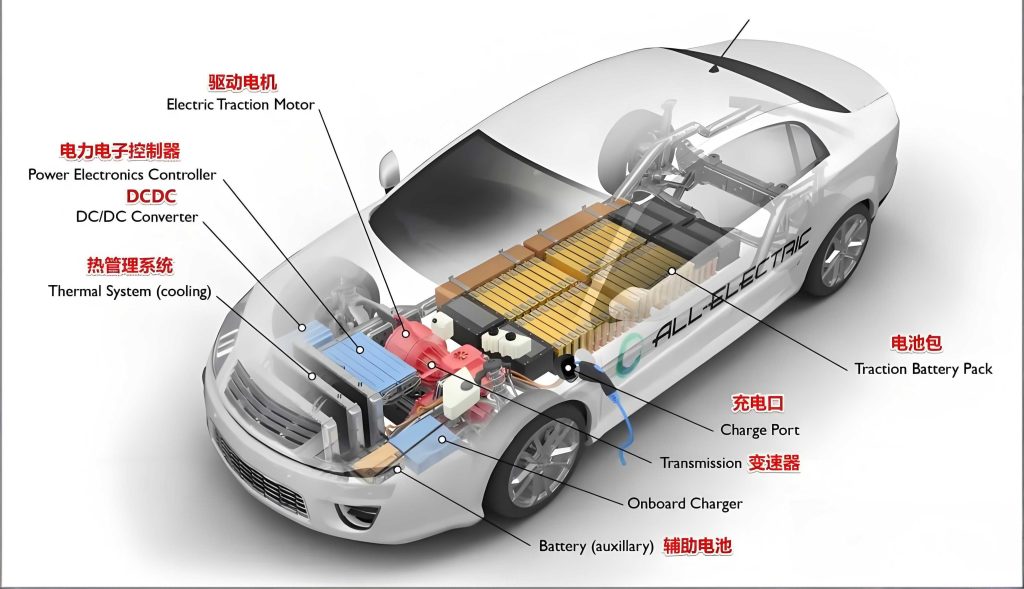

The push for sustainable transportation has positioned the battery electric car at the forefront of the automotive industry’s transformation. A critical enabler for the safety, performance, and longevity of a battery electric car is its Battery Thermal Management System (BTMS). The system’s core task is to maintain the lithium-ion battery pack within an optimal temperature window, typically 15–35°C, and to minimize temperature gradients across cells under diverse and often demanding operating conditions. While traditional BTMS designs and control strategies based on physical principles have laid the groundwork, they often struggle with model fidelity, real-time adaptability, and computational efficiency in complex, real-world scenarios.

The proliferation of onboard sensors and edge computing resources has opened new avenues for data-driven approaches. Machine Learning (ML), in particular, has emerged as a powerful paradigm to address the inherent complexities of BTMS modeling and control. From predicting thermal states with high accuracy to detecting subtle early-stage thermal anomalies and optimizing cooling control for energy efficiency, ML techniques are demonstrating significant potential to overcome the limitations of traditional methods. This review synthesizes the recent progress in applying ML to BTMS, providing a structured analysis of modeling tasks, methodological advances, control strategy optimization, and the crucial path toward lightweight, embedded deployment in the modern battery electric car.

1. Modeling Tasks, Scenarios, and Technological Evolution in BTMS

The design and operation of a BTMS for a battery electric car involve navigating a complex web of trade-offs between temperature control precision, spatial uniformity, energy consumption, system weight, and dynamic response. This complexity is intrinsically linked to the chosen cooling methodology.

1.1 Cooling Architectures and Associated Challenges

Different cooling solutions present distinct modeling and control challenges:

- Air Cooling: Relies on forced air convection. Its simplicity and low cost are advantageous, but its low heat capacity and thermal conductivity limit effectiveness under high loads, leading to significant temperature gradients. Modeling must capture non-uniform airflow and its impact on cell temperatures.

- Liquid Cooling: Employs a coolant (e.g., water-glycol mixture) circulated through cold plates or tubing. It offers superior heat transfer coefficients and temperature uniformity, especially for high-power applications common in a performance-oriented battery electric car. However, it introduces complexity with pumps, valves, and heat exchangers, and modeling must account for fluid-thermal coupling and pressure drops.

- Phase Change Material (PCM) Cooling: Uses materials that absorb heat during phase transition (e.g., solid to liquid). This passive method offers compact, zero-operational-power cooling but suffers from low thermal conductivity and potential saturation. Modeling challenges include capturing the non-linear heat transfer during phase change and the change in material properties over time.

- Heat Pipe Cooling: Utilizes the latent heat of a working fluid’s phase change cycle for highly efficient heat transport. Excellent for minimizing temperature differences and managing localized hot spots. Modeling complexities arise from two-phase flow dynamics and interfacial thermal resistance.

Each architecture dictates a unique set of multi-physics interactions—conduction, convection, and sometimes radiation—coupled with electrochemical heat generation within the battery cells. This multi-scale, strongly coupled nature makes high-fidelity modeling computationally expensive and motivates the exploration of data-driven surrogates.

1.2 Core Modeling Tasks and Their Intricacies

The intelligent operation of a BTMS can be deconstructed into three interconnected modeling tasks, each with specific demands on accuracy, robustness, and real-time capability.

1.2.1 Thermal State Modeling and Prediction

This task involves estimating the current and predicting the future temperature distribution of the battery pack using available sensor data (current, voltage, ambient temperature, coolant temperature/flow). The core challenge lies in the nonlinear, time-varying thermal dynamics influenced by electrical load, environmental conditions, and cooling system actions. While high-fidelity Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) models offer accuracy, their computational burden is prohibitive for real-time control in a battery electric car. Simplified lumped-parameter or equivalent circuit thermal models are faster but may lack spatial resolution. Data-driven models, trained on operational data, offer a promising middle ground by learning the complex input-output relationships directly.

1.2.2 Thermal Anomaly Detection

Early detection of faults like internal short circuits, which can precipitate thermal runaway, is vital for safety. The primary difficulty is the scarcity of labeled fault data, especially for early-stage, subtle anomalies. This makes supervised learning challenging. Consequently, unsupervised and semi-supervised methods are preferred, which learn a “normal” operational baseline from healthy data and flag significant deviations. Techniques like Autoencoders (AEs) or shape-based clustering of temperature time-series are effective in identifying incipient thermal faults without requiring explicit fault examples.

1.2.3 Cooling Control Strategy Optimization

This is the decision-making layer that commands actuators (fans, pumps, valves) to regulate temperature. The problem is a multi-objective optimal control task: minimize energy consumption and temperature spread while adhering to safety constraints (temperature limits). Traditional methods like Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control are simple but lack foresight and adaptability. Model Predictive Control (MPC) performs better by optimizing over a future horizon but is sensitive to model accuracy and computationally intensive. Reinforcement Learning (RL) has emerged as a powerful alternative, where an agent learns an optimal control policy through interaction with a simulation environment, potentially achieving better adaptability across diverse operating scenarios for a battery electric car.

1.3 Characteristic Operational Scenarios

The effectiveness of any BTMS model or controller is judged against its performance in realistic scenarios for a battery electric car:

- Environmental Extremes: Sub-zero temperatures require efficient battery heating, while scorching ambient conditions demand maximum cooling capacity without excessive energy drain.

- Dynamic Driving: Urban stop-and-go traffic, highway cruising, and aggressive acceleration impose highly variable thermal loads on the battery pack.

- Fast Charging: High-current charging generates substantial heat, making effective thermal management crucial to prevent overheating, reduce degradation, and enable charge acceptance.

- Integrated Thermal Management: In modern architectures, the BTMS may be coupled with the cabin air conditioning or heat pump system, requiring coordinated control to manage the vehicle’s total thermal load efficiently.

These scenarios highlight the need for models and controllers that are not just accurate but also robust and adaptive to a wide range of conditions.

2. Machine Learning for Thermal Modeling and State Prediction

Accurately predicting the thermal state is foundational for effective BTMS control. ML methods have shown remarkable success in learning the complex, nonlinear mappings from operational parameters to battery temperature.

2.1 Supervised Learning Paradigms

Supervised learning, utilizing labeled historical data, is the most direct approach for temperature prediction. Different algorithms offer varying trade-offs between accuracy, complexity, and interpretability.

A comparative analysis of common supervised models is summarized in the radar chart below, which evaluates them across five key dimensions: Prediction Accuracy, Training Complexity, Generalization Capability, Real-time Performance, and Deployability.

Key supervised methods include:

- Tree-based Models (e.g., XGBoost, Random Forest): Effective for capturing non-linearities and feature interactions. They generally offer good accuracy with moderate computational cost for training and inference, making them suitable for many prediction tasks. However, they may struggle with extreme extrapolation and temporal dependencies.

- Support Vector Machines (SVM) / Support Vector Regression (SVR): Powerful for high-dimensional spaces and can deliver good generalization with limited data when properly tuned. Their performance is sensitive to kernel and parameter selection.

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) & Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM): Specifically designed for sequential data. LSTMs excel at capturing long-term temporal dependencies in time-series data like temperature evolution, leading to high prediction accuracy. Their main drawback is higher computational cost and the need for larger datasets.

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Hybrid Models: CNNs can extract spatial features (e.g., from temperature sensor grids), while hybrid models like CNN-LSTM combine spatial and temporal feature learning, offering state-of-the-art performance for spatiotemporal prediction.

The choice of model depends heavily on the specific task, data availability, and onboard computational resources of the battery electric car.

2.2 Unsupervised and Semi-supervised Learning for Anomaly Detection

Given the lack of fault data, unsupervised learning is pivotal for thermal anomaly detection. These methods aim to model the distribution of normal operating data.

- Reconstruction-based Methods (e.g., Autoencoders): An AE is trained to compress and reconstruct normal input data (e.g., voltage, current, temperature sequences). During operation, a high reconstruction error indicates a deviation from the learned normal pattern, signaling a potential anomaly. Variants like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or Adversarial Autoencoders can improve detection sensitivity.

- One-class Classification & Clustering: Methods like One-Class SVM or Isolation Forest define a boundary around normal data points. K-Shape clustering groups time-series based on shape similarity; an abnormal cell’s temperature profile may form an outlier cluster.

- Semi-supervised and Graph-based Methods: When a small amount of labeled data is available, semi-supervised techniques (e.g., label propagation) can leverage both labeled and unlabeled data effectively. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are particularly promising as they can explicitly model the thermal coupling and topological relationships between cells in a battery pack, leading to more accurate early detection of faults that propagate.

The effectiveness of these methods is often measured by metrics like detection latency (how early a fault is caught) and the false positive rate.

2.3 Physics-Informed and Hybrid Modeling

A significant trend is the fusion of data-driven models with physical knowledge to create more robust and generalizable models, especially when data is scarce.

Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs): PINNs embed the governing physical laws (e.g., heat diffusion equations) directly into the loss function of a neural network during training. The total loss \( L \) is a composite of a data fidelity term and a physics residual term:

$$ L = L_{data} + \lambda L_{physics} $$

where \( L_{data} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^{N} | T_{pred}^{(i)} – T_{true}^{(i)} |^2 \) and \( L_{physics} \) ensures the network’s predictions satisfy the partial differential equation (PDE) \( \mathcal{F}(T; \lambda) = 0 \) and boundary conditions. The parameter \( \lambda \) balances the two constraints.

This approach ensures the model’s predictions are not only data-accurate but also physically plausible, improving performance in extrapolation and under unseen operating conditions critical for a battery electric car.

Grey-box / Hybrid Models: These models combine a simplified physical model (e.g., a lumped-parameter thermal network) with a data-driven component (e.g., a neural network) that corrects for the simplifications or unmodeled dynamics. The physical model provides structure and interpretability, while the data-driven component enhances accuracy.

2.4 Lightweight Modeling and Embedded Deployment

For real-world deployment in the resource-constrained electronic control units (ECUs) of a battery electric car, model complexity must be carefully managed. Research focuses on creating accurate yet lightweight models.

- Extreme Learning Machines (ELMs): Single-hidden-layer feedforward networks with randomly assigned input weights and analytically determined output weights. They offer extremely fast training and good generalization for many tasks with a compact structure.

- Model Compression Techniques:

- Pruning: Removing insignificant weights or neurons from a trained network.

- Quantization: Reducing the numerical precision of weights and activations (e.g., from 32-bit floating point to 8-bit integers).

- Knowledge Distillation: Training a small “student” network to mimic the behavior of a larger, more accurate “teacher” network.

- Neural Architecture Search (NAS): Automatically designing network architectures that are optimized for both accuracy and latency on target hardware.

The choice of software framework (TensorFlow Lite, PyTorch Mobile, ONNX Runtime) is also crucial for efficient deployment on automotive-grade hardware.

Table 1 provides a comparison of common ML frameworks and libraries used in BTMS development, highlighting their suitability for different tasks.

| Framework/Library | Primary Use Case in BTMS | Key Strengths | Limitations for Embedded | Typical Deployment Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TensorFlow / Keras | Complex DNN/LSTM model development and training | Extensive ecosystem, good for research prototyping | Runtime can be heavy; requires optimization (TF Lite) for edge | Cloud/Server training, edge inference via TF Lite |

| PyTorch | Flexible research, rapid prototyping of novel architectures | Dynamic computation graph, Pythonic | Similar to TF; needs conversion (TorchScript, ONNX) for deployment | Research, server-side, edge via libTorch |

| Scikit-learn | Classical ML (SVM, RF, XGBoost), feature engineering | Simple, efficient for traditional algorithms | Not for deep learning; some algorithms can be memory intensive | Edge deployment possible for light models (e.g., with sklearn-porter) |

| MATLAB/Simulink | Control-oriented modeling, MPC design, HIL testing | Excellent for control system integration, physical modeling | Proprietary, cost, generated code may not be optimal | Rapid Control Prototyping (RCP), HIL systems |

3. Control Methods and Optimization Strategies for BTMS

An intelligent control strategy is the actuator that translates thermal state predictions into efficient and safe cooling actions. The evolution from traditional to learning-based controllers marks a significant step toward adaptability.

3.1 Control Objectives and Performance Metrics

The performance of a BTMS controller is evaluated against multiple, often competing, objectives:

- Temperature Regulation: Maintain average pack temperature \( T_{avg} \) within \( [T_{min}, T_{max}] \). Metrics: Absolute error \( |T_{avg} – T_{ref}| \), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Temperature Uniformity: Minimize the maximum temperature difference \( \Delta T_{max} = T_{max,cell} – T_{min,cell} \) or the standard deviation \( \sigma_T \).

- Energy Efficiency: Minimize the energy consumed by the cooling system \( E_{cool} \). A common metric is the Coefficient of Performance (COP) for heat pump systems or simply the total electrical energy used by fans/pumps.

- Dynamic Response: Minimize overshoot \( OS \) and settling time \( t_s \) after a step change in load or ambient condition.

- Battery Health Consideration: Indirectly maximize battery life by minimizing exposure to high temperatures and large cycles. Can be integrated via a degradation model in the cost function.

A comprehensive cost function \( J \) for an optimization-based controller might combine these:

$$ J = \sum_{k=0}^{N-1} \left( \alpha (T_{avg}(k) – T_{ref})^2 + \beta (\Delta T_{max}(k))^2 + \gamma P_{cool}(k) \right) $$

where \( \alpha, \beta, \gamma \) are weighting factors, and \( N \) is the prediction horizon.

3.2 Classification of Control Strategies

3.2.1 Traditional and Model-Based Control

- PID Control: The industry workhorse. Simple, reliable, but requires careful tuning and performs poorly with strong nonlinearities and multiple coupled variables.

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): A more advanced model-based strategy. At each control interval, MPC solves a finite-horizon optimization problem using a model of the BTMS to predict future states. It selects a sequence of control actions that minimizes the cost function \( J \) while respecting constraints (e.g., \( T_{max} \), \( P_{pump,max} \)). Its performance is highly dependent on the accuracy of the internal model, which is often a simplified thermal model or a data-driven surrogate.

3.2.2 Data-Driven and Learning-Based Control

This category leverages ML not just for prediction, but directly for control decision-making.

- ML-Enhanced MPC: A data-driven model (e.g., a neural network) serves as the fast, internal prediction model within the MPC framework, replacing slower physics-based models. This improves the controller’s accuracy and real-time feasibility.

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): Represents a paradigm shift. An RL agent learns a control policy \( \pi(a|s) \)—a mapping from system state \( s \) (temperatures, loads, ambient) to action \( a \) (pump speed, fan duty cycle)—by interacting with a simulation environment to maximize a cumulative reward \( R \). The reward function encodes the control objectives (e.g., \( R = -(\alpha \Delta T^2 + \gamma P_{cool}) \)).

Table 2 compares prominent RL algorithms applied to BTMS control.

| Algorithm | Action Space | Key Characteristics | BTMS Application Example | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Q-Network (DQN) | Discrete | Learns action-value function Q(s,a). Good for on/off or multi-level control. | Optimizing fan speed levels or valve on/off states. | Curse of dimensionality for fine-grained continuous control. |

| Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) | Continuous | Actor-Critic method. Suitable for fine-tuning continuous actuators like pump speed. | Precise control of coolant flow rate in a liquid cooling loop. | Sensitive to hyperparameters, can be unstable during training. |

| Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) | Discrete/Continuous | Policy gradient method with clipped updates. Known for stability and ease of tuning. | General thermal management policy learning for combined cooling systems. | May require more environment interactions than DQN. |

| Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) | Continuous | Maximum entropy RL. Encourages exploration and is generally robust. | Multi-objective optimization balancing temperature, uniformity, and energy. | More complex than PPO, with more hyperparameters. |

3.2.3 Multi-objective Optimization and Decision Making

The core of BTMS control is a multi-objective optimization (MOO) problem. Techniques like the Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II) can be used offline to explore the Pareto front of optimal design trade-offs (e.g., system weight vs. cooling performance). For online control, the weighting factors in the cost function \( J \) embody a specific trade-off. Advanced strategies may adapt these weights online based on driving mode or battery state of health.

3.3 Engineering Deployment and Lightweight Control

Translating advanced controllers from simulation to the ECU of a battery electric car requires addressing stringent real-time and memory constraints.

- Explicit MPC (eMPC): Pre-computes the optimal control law offline as a piecewise affine function of the state. Online control reduces to a simple lookup and linear function evaluation, drastically cutting computation time at the cost of increased memory usage.

- Lightweight RL Policies: The neural network representing the learned RL policy can be compressed using the techniques mentioned in Section 2.4 (pruning, quantization). A small, quantized policy network can execute with very low latency.

- Hardware-in-the-Loop (HIL) Testing: A critical step before vehicle integration. The controller software runs on the target ECU or a representative processor, connected to a real-time simulator that models the battery, thermal system, and vehicle dynamics. This validates functionality, real-time performance, and robustness.

The ultimate goal is a certifiable (e.g., ISO 26262 compliant), efficient, and adaptive controller that reliably manages the thermal state of the battery pack throughout the life of the battery electric car.

4. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The integration of Machine Learning into the Battery Thermal Management System represents a significant leap toward smarter, more efficient, and more adaptive battery electric cars. This review has outlined the progression from traditional modeling and control to data-driven paradigms, highlighting key applications in thermal state prediction, anomaly detection, and control optimization.

Supervised learning models, particularly deep sequential networks like LSTMs and hybrid spatiotemporal models, have proven highly effective for accurate temperature prediction. Unsupervised and semi-supervised methods are indispensable for early fault detection in the absence of labeled failure data. For control, while MPC remains a powerful model-based framework, Reinforcement Learning offers a compelling model-free alternative capable of learning complex, adaptive policies that can simultaneously optimize for temperature, uniformity, and energy consumption.

However, the path to widespread industrial adoption in battery electric cars is paved with ongoing challenges:

- Bridging the Simulation-to-Reality Gap: RL policies trained in simulation may not generalize perfectly to the real world due to model inaccuracies. Advanced techniques like domain randomization and real-world data fine-tuning are essential.

- Safety and Verification: Learning-based controllers, especially RL, are often seen as “black boxes.” Developing methods for safety verification, robust constraint handling (Safe RL), and explainability is critical for functional safety certification.

- Lifelong Adaptation: Battery characteristics degrade over time. Future BTMS should incorporate continual learning or adaptive mechanisms to adjust models and control policies as the battery ages, ensuring consistent performance throughout the vehicle’s life.

- Tight Hardware-Software Co-design: The ultimate success depends on ultra-efficient algorithms paired with appropriate automotive-grade hardware (e.g., AI accelerators). Research into TinyML and specialized neural network architectures for thermal management will be key.

- Integrated Vehicle-Wide Thermal Management: The next frontier is the co-optimization of the BTMS with the cabin HVAC and powertrain cooling systems using multi-agent RL or system-level optimization to maximize the total energy efficiency of the battery electric car.

In conclusion, ML is not merely an incremental improvement but a transformative tool for BTMS. By enabling more accurate predictions, proactive safety interventions, and highly efficient, adaptive control, ML-driven BTMS will play a central role in unlocking the full potential of electric mobility—enhancing range, prolonging battery life, and ensuring the safe and reliable operation of every battery electric car on the road.