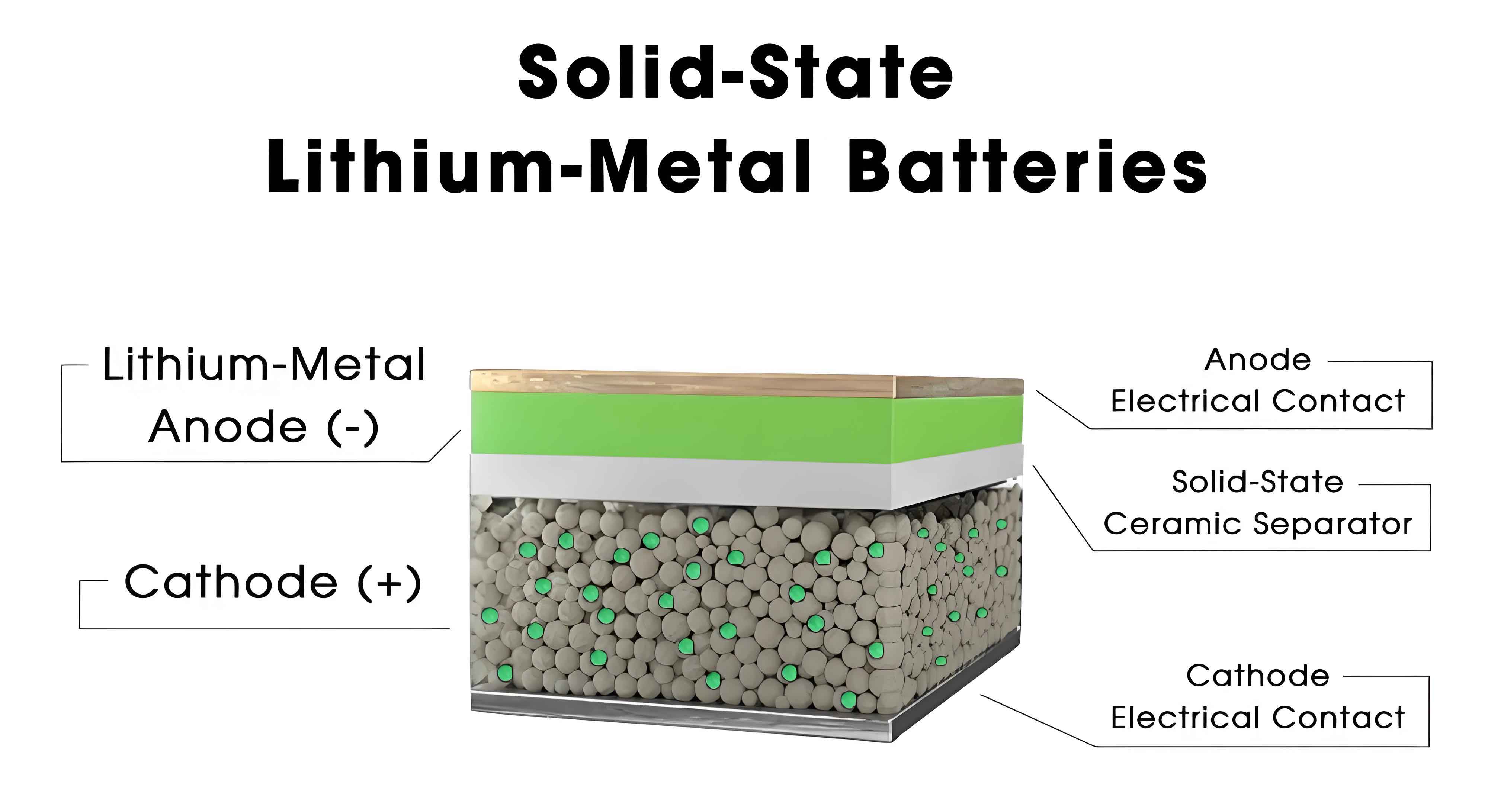

All-solid-state batteries represent a transformative advancement in energy storage technology, offering the potential for higher energy density and enhanced safety compared to conventional lithium-ion batteries. Among various solid electrolytes, sulfide-based systems have garnered significant attention due to their exceptional ionic conductivity, which rivals that of liquid electrolytes, and their favorable mechanical properties that facilitate processing. However, the transition from laboratory research to commercial deployment of sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries is fraught with challenges, spanning fundamental material science to large-scale engineering. This article delves into the core scientific hurdles and practical obstacles associated with sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries, proposing strategic directions to accelerate their development and industrialization.

The pursuit of high-performance energy storage systems has intensified with the growing demand for electric vehicles, portable electronics, and grid-scale storage. Traditional lithium-ion batteries, while widely adopted, face limitations in energy density and safety risks due to flammable organic electrolytes. In contrast, all-solid-state batteries replace liquid electrolytes with solid counterparts, mitigating leakage and thermal runaway risks. Sulfide solid electrolytes, such as Li10GeP2S12 (LGPS) and Li6PS5Cl (LPSCl), exhibit ionic conductivities exceeding 10 mS/cm at room temperature, making them prime candidates for next-generation all-solid-state batteries. Despite these advantages, issues like interfacial instability, moisture sensitivity, and manufacturing complexities impede progress. This review systematically addresses these challenges, emphasizing the interplay between material properties and engineering processes in sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries.

Fundamental Scientific Challenges in Sulfide-Based All-Solid-State Batteries

The performance of sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries is governed by the intrinsic properties of sulfide solid electrolytes and their interactions with electrode materials. Key scientific challenges include electrolyte stability, interfacial compatibility, and electrochemical degradation mechanisms.

Stability Issues of Sulfide Solid Electrolytes

Sulfide solid electrolytes face critical stability concerns under operational conditions, affecting the longevity and safety of all-solid-state batteries. These include electrochemical, humidity, and thermal stability, each requiring tailored mitigation strategies.

Electrochemical Stability: The narrow electrochemical window of sulfide electrolytes limits their compatibility with high-voltage cathodes and low-potential anodes. For instance, LPSCl decomposes when the voltage exceeds its stability range, forming products like Li3PS4, S, and LiCl. The electrochemical window (ΔE) can be approximated using the bandgap (Eg) between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO):

$$ \Delta E = E_{\text{LUMO}} – E_{\text{HOMO}} $$

For typical sulfide electrolytes, ΔE ranges from 1.7 to 2.1 V, necessitating protective coatings or dopants to extend the operational voltage. Elemental doping with O or F can induce the formation of stable interphases (e.g., LiF or Li2O), which passivate the electrolyte and suppress further decomposition. Computational studies using density functional theory (DFT) have identified promising coating materials, such as sulfur- or selenium-based layers, to enhance stability at high voltages.

Humidity Stability: Sulfide electrolytes are highly susceptible to hydrolysis in moist environments, releasing toxic H2S gas. This reaction is driven by the soft acid-base interactions, where S2− ions react with H+ from water. The hydrolysis energy (ΔGhydrolysis) for common sulfides is negative, indicating spontaneity:

$$ \Delta G_{\text{hydrolysis}} < 0 $$

Strategies to improve humidity stability include elemental substitution (e.g., Sn, Sb, O doping) and surface passivation with hydrophobic layers like LiF. For example, Sb-doped LGPS reduces H2S emission by over 90%, albeit with a slight trade-off in ionic conductivity. Surface treatment with HF gas forms a protective LiF coating, significantly enhancing air stability without compromising bulk properties.

Thermal Stability: At elevated temperatures, sulfide electrolytes can decompose exothermically, posing thermal runaway risks in all-solid-state batteries. The thermal stability parameter (Th′) accounts for crystal structure and bond energies:

$$ T_h’ = f(\text{structure}, \text{bond energy}, \text{coordination number}) $$

Doping with elements like Cu or Sn increases Th′, improving thermal resilience. However, Cl-rich compositions in LPSCl may reduce thermal stability due to weaker bonds. Interactions with oxide cathodes (e.g., NCM811) at high temperatures lead to oxygen release and reactive decomposition, necessitating interface engineering or O2 removal systems.

Interfacial Challenges with Cathode Materials

The solid-solid interface between sulfide electrolytes and cathode materials is a critical bottleneck in all-solid-state batteries. Issues include poor contact, chemical reactions, element interdiffusion, and space-charge layer effects.

Constructing Effective Interfaces: Volume changes in cathode materials during cycling cause contact loss and increased impedance. For example, LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) exhibits anisotropic expansion, leading to microcracks and interface degradation. Reducing particle size and designing gradient structures mitigate stress and maintain contact. Computational models show that smaller cathode particles enhance Li+ percolation pathways, improving rate capability.

Energy Level Mismatch: The disparity between the HOMO of sulfide electrolytes and the Fermi level of cathodes triggers oxidative decomposition. Carbon additives in composite cathodes can accelerate this process by facilitating electron transfer. In-situ Raman spectroscopy reveals side products like Li2S and LiCl at the interface, increasing resistance over cycles.

Elemental Stability and Space-Charge Layers: Interdiffusion of elements (e.g., Co and P) forms insulating phases, while space-charge layers arise from Li+ chemical potential gradients. The space-charge layer thickness (λ) is given by:

$$ \lambda = \sqrt{\frac{\epsilon RT}{2F^2 C_0}} $$

where ε is the permittivity, R the gas constant, T temperature, F Faraday’s constant, and C0 the bulk Li+ concentration. Coating cathodes with buffer layers (e.g., Li2O, LiNbO3) suppresses diffusion and stabilizes the interface. Oxygen substitution in sulfide electrolytes (e.g., Li6PO4SCl) also reduces space-charge effects by aligning energy levels.

Interfacial Challenges with Anode Materials

Anode compatibility is crucial for achieving high energy density in all-solid-state batteries. Sulfide electrolytes face distinct issues with graphite, silicon, and lithium metal anodes.

Graphite Anodes: Graphite offers good electronic conductivity but suffers from Li plating at high currents due to slow Li+ diffusion. Coating graphite with LiI or single-ion conductors (e.g., Li3BO3-Li2CO3) creates stable solid electrolyte interphases (SEI), enabling fast charging up to 4 C. Composite electrodes with core-shell structures (e.g., graphite@LPSCl) improve Li+ transport and reduce polarization.

Silicon Anodes: Silicon’s high theoretical capacity (3579 mAh/g) is offset by large volume changes (>300%), causing mechanical failure. Nanostructuring and carbon compositing alleviate strain, while in-situ polymer coatings (e.g., lithium polyacrylate) enhance adhesion and cycling stability. Dry-processing methods produce robust silicon electrodes with high mass loading for all-solid-state batteries.

Lithium Metal Anodes: Lithium metal provides the highest energy density but reacts with sulfide electrolytes, forming resistive interphases. Dendrite growth along grain boundaries remains a critical failure mode. Artificial SEI layers (e.g., Al2O3 via atomic layer deposition) and halogen-rich electrolytes (e.g., Li7−xPS6−xClx) promote LiCl-rich interfaces that inhibit dendrites. 3D lithium architectures, formed via spontaneous reactions with halide electrolytes, enable uniform deposition and extended cycle life in all-solid-state batteries.

Engineering Challenges in Sulfide-Based All-Solid-State Batteries

Scaling up sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries involves overcoming manufacturing hurdles related to electrolyte synthesis, membrane fabrication, and cell assembly. These processes must balance cost, performance, and reproducibility.

Large-Scale Production and Cost Control of Sulfide Electrolytes

Industrial production of sulfide electrolytes requires methods that ensure high ionic conductivity, phase purity, and cost-effectiveness. The primary approaches include high-temperature solid-state and liquid-phase synthesis.

| Synthesis Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Ionic Conductivity (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Temperature Solid-State | High purity, tunable phases | Energy-intensive, particle size variability | 1–10 |

| Liquid-Phase | Uniform particles, scalable | Solvent residues, lower conductivity | 0.1–5 |

Cost reduction hinges on affordable raw materials, particularly Li2S, which accounts for over 30% of material costs. Substituting Li2S with Li2O or using metathesis reactions (e.g., Na2S + LiCl → Li2S) can lower expenses to under $20/kg. Automated, continuous processes in moisture-controlled environments are essential for large-scale output, with throughput targets exceeding 100 tons annually.

Electrolyte Membrane Fabrication Processes

Producing thin, robust electrolyte membranes is vital for high-energy-density all-solid-state batteries. Wet and dry processing methods each present unique benefits and limitations.

Wet Processing: This technique involves dissolving sulfide electrolytes and binders in solvents (e.g., N-methylpyrrolidone) to form slurries, which are cast and dried. It ensures good contact but risks solvent-induced degradation and environmental harm. Innovations like non-polar solvents (e.g., toluene) and gel polymer additives improve compatibility and yield membranes as thin as 25 μm with ionic conductivities around 1–2 mS/cm.

Dry Processing: Solvent-free methods, such as mechanical pressing with binders like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), avoid chemical degradation and enable ultrathin membranes (<30 μm). However, achieving uniform mixing and preventing PTFE-derived carbon formation are challenges. Modified binders with ion-conductive groups (e.g., sulfonated polymers) enhance Li+ transport, with reported conductivities up to 8.4 mS/cm for dry-processed membranes.

The table below compares key properties of sulfide electrolyte membranes:

| Electrolyte | Binder | Thickness (μm) | Ionic Conductivity (mS/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Li6PS5Cl | Poly(butyl methacrylate) | 40 | 0.86 |

| Li6PS5Cl | Ethyl cellulose | 47 | 1.65 |

| Li5.4PS4.4Cl1.6 | PTFE | 30 | 8.4 |

| Li10GeP2S12 | PTFE | 100 | 0.36 |

Assembly and Stacking of All-Solid-State Batteries

Cell assembly methods directly impact the performance and scalability of all-solid-state batteries. Common approaches include self-supporting and cathode-supported stacking, followed by densification to ensure intimate contact.

Stacking Techniques: Single-layer stacking arranges cathode, electrolyte, and anode layers in a planar configuration, suitable for small cells but prone to alignment errors. Z-fold stacking increases electrode area density but requires precision equipment. Bipolar stacking reduces inactive materials and boosts module-level energy density, though it demands sophisticated double-sided electrode fabrication.

Densification Methods: Applying pressure is critical to minimize porosity and enhance interfacial contact. Techniques include:

- Roll Pressing: High throughput but may cause inhomogeneity at pressures >300 MPa.

- Uniaxial Pressing: Effective for lab-scale cells but scales poorly with area.

- Isostatic Pressing: Uniform pressure distribution, ideal for large formats, though costly and slow.

The choice of assembly method influences the overall energy density and cycle life of all-solid-state batteries. For instance, bipolar stacks can achieve voltages >100 V in a single package, while Z-fold designs optimize space utilization in pouch cells.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries hold immense promise for revolutionizing energy storage, yet their commercialization hinges on resolving multifaceted challenges. Fundamental issues like electrolyte stability and interfacial degradation require continued material innovation, such as multi-element doping and advanced coatings. Engineering hurdles in scalable synthesis, membrane fabrication, and cell assembly demand process optimization and cost reduction. Future efforts should focus on:

- Material Innovation: Developing sulfide electrolytes with enhanced humidity and thermal stability through computational-guided design and novel composites.

- Interface Engineering: Implementing dynamic interface management strategies using in-situ characterization and artificial SEI layers to prolong cycle life.

- Process Optimization: Advancing dry processing and automated assembly to produce thin, consistent membranes and cells at industrial scale.

- Battery Design: Integrating high-capacity electrodes (e.g., silicon anodes, high-nickel cathodes) with optimized thermal management for high-energy-density all-solid-state batteries.

- Standardization and Collaboration: Establishing industry-wide testing protocols and fostering academia-industry partnerships to accelerate adoption.

With concerted research and development, sulfide-based all-solid-state batteries can achieve their full potential, enabling safer, higher-energy storage solutions for electric transportation and grid applications. The journey from lab to market will require interdisciplinary collaboration, but the rewards—a sustainable energy future—are well worth the effort.