China cemented its position as the world’s largest automotive exporter in 2024, shattering records with 6.41 million vehicles shipped globally – a robust 23% year-on-year increase. This unprecedented milestone, however, unfolds against a backdrop of escalating international trade friction. As Chinese automakers, spearheaded by giants like BYD, Chery, Great Wall, and SAIC, aggressively expand their overseas footprint, particularly with China electric vehicles, they find themselves increasingly navigating a complex labyrinth of rising tariffs and protectionist policies. The path to sustained global dominance hinges on strategic localization and innovative “technology exports” to circumvent these barriers.

The export boom is underpinned by undeniable competitive advantages. “The explosion in China’s auto exports fundamentally reflects Chinese companies’ strengths in product capability, supply chain efficiency, and pricing,” asserts Lu Shengyun, founder of consultancy Qianjuezhenshen and former R&D engineer at PSA Peugeot Citroën. Independent brands like Chery, SAIC, Changan, Geely, and Great Wall form the vanguard, while joint ventures like Ford China and Beijing Hyundai are increasingly leveraging China as a production and export hub in a phenomenon dubbed “reverse exporting.”

Russia emerged as the dominant market in 2024, absorbing 1.158 million Chinese vehicles, significantly outpacing second-place Mexico (445,000 units) and third-place UAE (330,600 units). This surge, initially a staggering 459% year-on-year increase in 2023 fueled by the departure of Western brands following the Ukraine crisis, now faces significant headwinds. In October 2024, Russia announced a drastic 70-85% hike in its vehicle scrappage tax (based on engine displacement), effective January 2025, with subsequent annual increases of 10-20% planned until 2030. Industry insiders interpret this as a de facto tariff barrier.

“This essentially means raising tariff walls by stealth,” explained a veteran with nine years in parallel auto imports. “The import cost for a 2.0L displacement vehicle will increase by 20,000 to 30,000 yuan immediately, rising to around 70,000 yuan by 2030.” Xu Haidong, Deputy Secretary-General of the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM), predicts this will slash exports to Russia to approximately 800,000 units in 2025. “Although exports to Russia face challenges, other key markets – including South America, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Africa, and developed nations like the UK and Australia – are expected to maintain growth momentum,” Xu added, highlighting the need for market diversification.

Mexico, the world’s seventh-largest auto producer, solidified its position as China’s second-largest export destination. Lu Shengyun notes Mexico’s domestic market is relatively limited, with its auto industry heavily oriented towards export. The UAE and Belgium rounded out the top four, receiving 330,600 and 280,000 vehicles respectively. Notably, while exports to the UAE were predominantly internal combustion engine models, shipments to Belgium consisted mainly of China electric vehicles. Belgium serves as a critical transshipment hub for Chinese automakers entering the broader European market. The Port of Antwerp, Europe’s second-largest port and its largest automotive hub, offers advantageous customs and tax policies via its free trade port status, bolstering competitiveness – a role increasingly vital as the EU erects its own barriers.

The European Union’s stance presents arguably the most significant challenge. Its investigation into China electric vehicle subsidies and the looming threat of punitive tariffs have forced a strategic pivot. “After encountering ‘tariff’ resistance in Europe, Chinese automakers like BYD, Chery, and Great Wall are accelerating plans for overseas production bases,” the industry observes. Great Wall Motor Chairman Wei Jianjun has been vocal in urging Chinese car companies to expedite global manufacturing footprints. “Chinese automakers should accelerate globalization, achieve localized production in major markets to reduce costs, and build stronger international competitiveness,” he stated. Localization is no longer optional; it’s imperative for survival and growth in key regions like Europe.

This shift towards local production is manifesting rapidly. BYD is leading the charge, announcing its first European electric vehicle plant in Hungary and actively scouting locations for a second facility. Chery is also aggressively pursuing European manufacturing, signing an agreement with Spain’s Ebro-EV Motors. SAIC Motor, leveraging its established MG brand, is reportedly exploring European production options to mitigate tariff impacts. Leapmotor is adopting a partnership model, utilizing Stellantis’s existing European manufacturing capacity rather than building its own plants. “We are advancing European localization, relying more on our partner’s (Stellantis) manufacturing capabilities; we won’t invest in building factories ourselves,” a Leapmotor executive clarified. Beyond Europe, Chery, Great Wall, Changan, and SAIC have already established or acquired multiple overseas production bases across other regions.

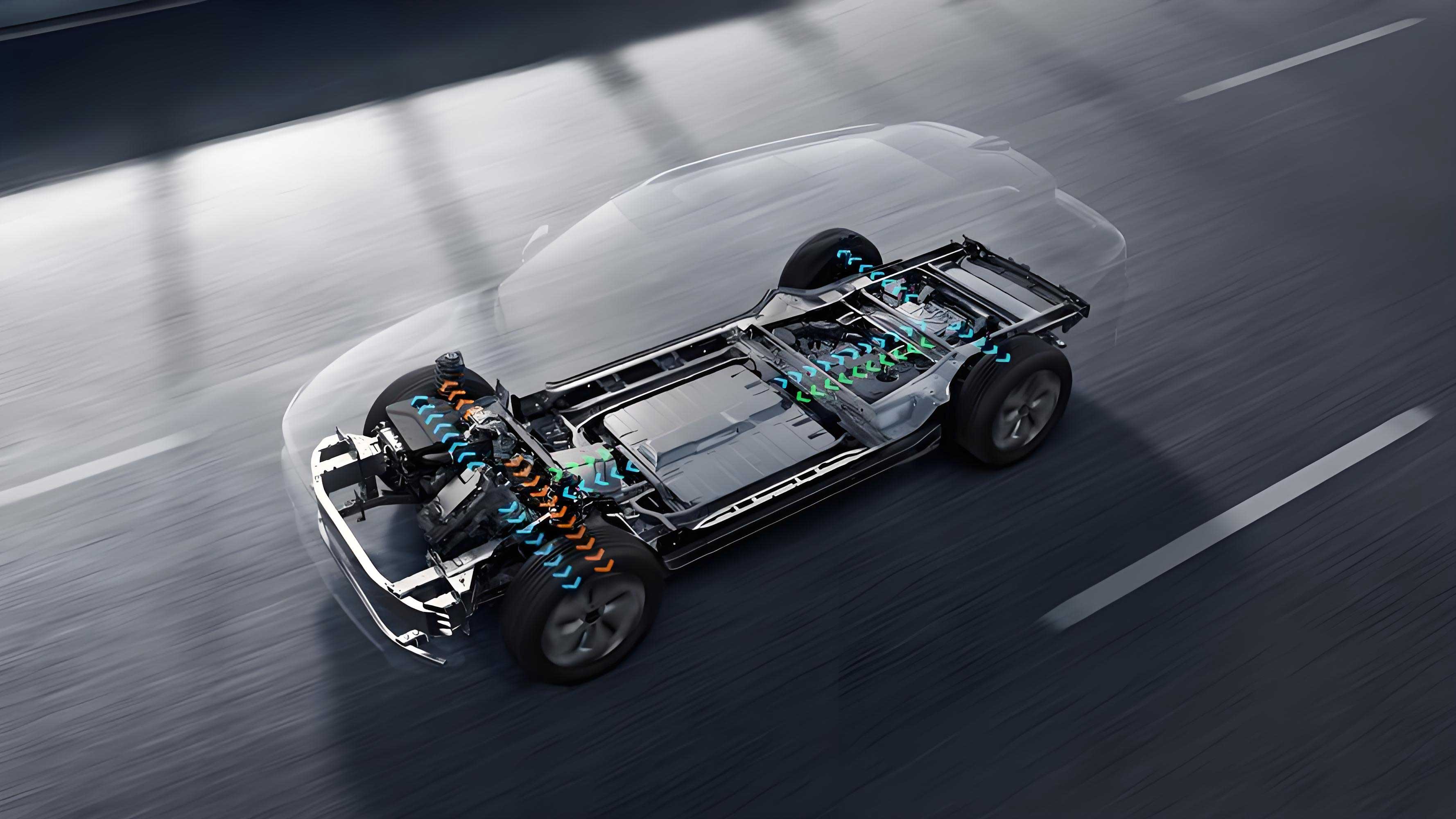

Complementing the localization drive, industry leaders advocate for a parallel strategy: “technology exports.” Chinese automakers possess a recognized edge in electric vehicle and intelligent driving technologies. Lu Shengyun emphasizes, “Chinese automakers are a step ahead of foreign manufacturers in new energy technology and smart driving tech. They can license these technologies. Leapmotor itself has stated it aims to be not just a vehicle manufacturer but a core technology supplier.” He adds a crucial insight gleaned from European sentiment: “Europeans hope the Chinese will ‘teach’ them how to build electric vehicles, not just sell them cars.”

Currently, XPeng and Leapmotor are pioneers in this “technology export” model. XPeng and Volkswagen are jointly developing B-segment electric vehicles based on XPeng’s G9 platform, smart cabin technology, and advanced driver-assistance software, leveraging each other’s core strengths. Similarly, Stellantis utilizes Leapmotor’s technology to produce and sell electric vehicles under its own brands in global markets outside China. This approach offers a pathway to generate revenue and build influence without directly flooding markets with Chinese-branded vehicles, potentially alleviating some political resistance.

However, navigating European investment desires remains delicate. Sun Xiaohong, Secretary-General of the Automotive Branch of the China Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Machinery and Electronic Products (CCCME), observes the complexity: “The EU wants Chinese automotive investment but has many reservations. They hope China electric vehicles will come but not grow too rapidly; they want industrial investment to create jobs and bring technology transfer, but they don’t want Chinese companies to become dominant locally.” Chery Chairman Yin Tongyue offered a pragmatic reminder for Chinese brands expanding overseas: “Chinese auto companies are guests abroad; they cannot try to usurp the host’s role.” Balancing ambition with local sensitivities is paramount.

The US market adds another layer of uncertainty. Former President Donald Trump’s rhetoric threatening a potential 60% tariff on Chinese cars, or even an outright ban, looms large. Ford CEO Jim Farley’s comment that Chinese automakers pose the “biggest competitive threat” underscores the anxiety within the established US auto industry. While direct Chinese brand penetration in the US passenger vehicle market remains minimal currently, the potential for disruption via Mexico or future direct exports keeps this threat high on the radar.

Looking ahead to 2025, the landscape is fraught with complexity. The combination of Russia’s escalating scrappage taxes, the EU’s anticipated tariffs on electric vehicles, and potential US protectionism creates significant headwinds. The days of relying solely on exporting finished vehicles from China are rapidly receding. Success hinges on a dual-track approach: aggressive localization of manufacturing to circumvent tariffs and reduce logistics costs, coupled with strategic “technology exports” that monetize China electric vehicle and software leadership while fostering international partnerships. Companies mastering this transition – building local factories, forging technology alliances like XPeng-VW and Leapmotor-Stellantis, and navigating geopolitical sensitivities – will be best positioned to convert China’s export volume supremacy into sustainable, long-term global market leadership. The race is no longer just about selling more cars; it’s about embedding Chinese automotive technology and manufacturing prowess deep within the global supply chain, with China electric vehicles at the forefront of this transformative shift. The 6.41 million mark is a historic achievement, but the true test of China’s automotive ambition is just beginning.