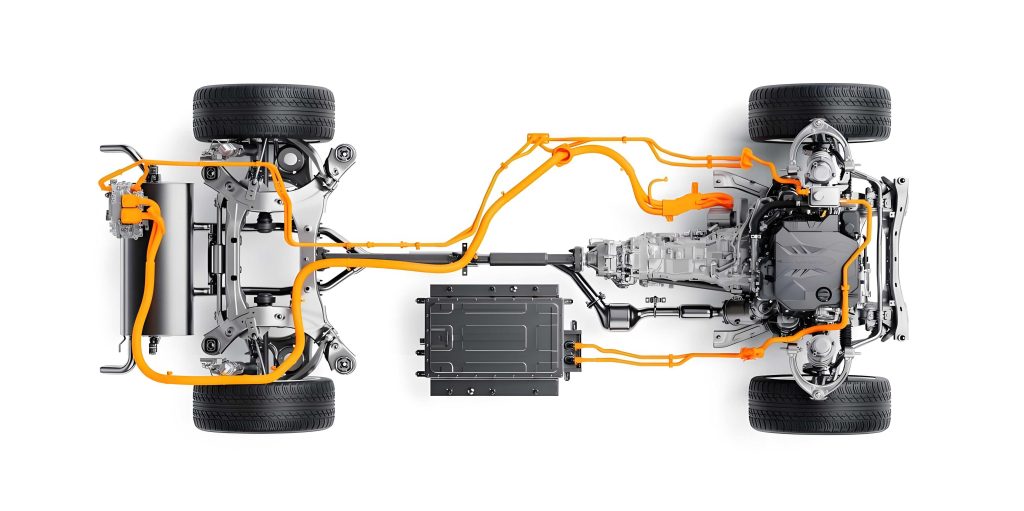

In the automotive industry, Noise, Vibration, and Harshness (NVH) performance is a critical factor influencing customer satisfaction and perceived quality, especially for hybrid electric vehicles. These vehicles combine internal combustion engines and electric motors, introducing unique NVH challenges due to multiple power sources and new components like high-voltage systems. As a research team specializing in NVH development, we encountered a specific issue in a hybrid electric vehicle model: a distinct booming noise during acceleration in hybrid direct drive mode. This article details our first-person investigation, diagnosis, and optimization process to resolve this problem, emphasizing the role of structural resonances in high-voltage harness brackets. We will employ extensive data analysis, incorporate formulas and tables, and discuss implications for hybrid electric vehicle design.

The proliferation of hybrid electric vehicles has reshaped NVH landscapes. Traditional noise paths like engine mounts and exhaust systems are now accompanied by new transfer paths from electric drivetrains and high-voltage components. In our project, the subject hybrid electric vehicle operates in multiple modes: series mode (engine acts as a generator) and hybrid direct drive mode (engine directly drives the wheels with electric motor assist). The latter mode, particularly in first gear under light throttle acceleration, exhibited an objectionable “booming” or “buzzing” sound inside the cabin at an engine speed of approximately 2200 r/min. This phenomenon not only affected comfort but also highlighted potential design oversights in the integration of high-voltage systems. For hybrid electric vehicles, such issues can undermine their premium positioning, making rapid diagnosis and solution imperative.

Our initial step involved a subjective evaluation of four prototype vehicles. Consistently, all vehicles displayed the booming noise in the specified operating condition. To objectively characterize the issue, we instrumented a vehicle with microphones at the driver’s right ear and tri-axial accelerometers at key locations: engine mounts (active and passive sides), firewall, and notably, the brackets supporting the high-voltage harness and Power Distribution Unit (PDU). Testing was conducted on smooth asphalt roads with light-throttle acceleration to 70 km/h. Time-domain data was transformed into the frequency domain for analysis.

Using band-pass filtering and order analysis techniques, we isolated the problematic frequency component. The driver’s ear sound pressure level spectrum revealed a prominent peak at 150 Hz. Since the noise occurred at 2200 r/min, we calculated the corresponding engine orders. The fundamental relationship between frequency, engine speed, and order is given by:

$$ f = \frac{N \times n}{60} $$

where \( f \) is the frequency in Hz, \( N \) is the engine speed in revolutions per minute (r/min), and \( n \) is the engine order. For \( N = 2200 \) r/min and \( n = 4 \) (the fourth engine order, often dominant due to cylinder firing impulses), the frequency is:

$$ f = \frac{2200 \times 4}{60} = 146.67 \approx 150 \text{ Hz} $$

This confirmed the booming noise as a 4th-order engine noise at 150 Hz. Audio playback of the 150 Hz band-pass filtered signal matched the subjective perception, solidifying this frequency as the target.

| Measurement Location | Direction | Acceleration (m/s²) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Engine Mount (Active) | Vertical (Z) | 8.5 | Within normal range |

| Exhaust Hanger (Active) | Vertical (Z) | 6.2 | Within normal range |

| Firewall | Vertical (Z) | 4.1 | Within normal range |

| High-Voltage Harness Bracket | X (Fore-Aft) | 16.0 | Significantly high |

| High-Voltage Harness Bracket | Z (Vertical) | 12.5 | Significantly high |

As shown in Table 1, while traditional paths exhibited normal vibration levels, the high-voltage harness bracket showed exceptionally high vibration amplitudes at 150 Hz, suggesting a resonance. This was a critical finding, as high-voltage components in hybrid electric vehicles often have stiffer brackets for safety and reliability, which can inadvertently create new structural noise transfer paths if not properly tuned.

We then investigated the vehicle’s Noise Transfer Functions (NTFs) around 150 Hz and found no abnormal peaks, indicating that the body panel responses were not the primary issue. The focus shifted to the high-voltage harness system as a potential amplifier. To test the resonance hypothesis, we performed a modal test on the bracket system in its installed condition. Using impact hammer testing and measuring frequency response functions (FRFs), we identified a dominant modal frequency. The average result from multiple test points is summarized below:

| Component | Test Direction | Peak Frequency (Hz) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDU Bracket | X (Fore-Aft) | 154 | Primary mode shape |

| PDU Bracket | Z (Vertical) | 152 | Primary mode shape |

| Firewall near bracket | X | 156 | Coupled vibration |

| Firewall near bracket | Z | 153 | Coupled vibration |

The modal frequency clustered around 150-155 Hz, directly coinciding with the 4th-order excitation frequency at 2200 r/min. This resonance explained the high vibration levels: the bracket’s dynamic response was amplified, transmitting significant energy into the body structure, which radiated as airborne noise inside the cabin. This is a classic forced vibration problem where the excitation frequency matches a natural frequency, leading to high amplitude response. The equation governing the response amplitude \( X \) for a single-degree-of-freedom system under harmonic excitation is:

$$ X = \frac{F_0/k}{\sqrt{(1-r^2)^2 + (2\zeta r)^2}} $$

where \( F_0 \) is the excitation force amplitude, \( k \) is the stiffness, \( r = \omega / \omega_n \) is the frequency ratio, \( \omega \) is the excitation frequency, \( \omega_n \) is the natural frequency, and \( \zeta \) is the damping ratio. At resonance (\( r \approx 1 \)), the amplitude is limited primarily by damping. In our case, the bracket system had low damping, leading to high vibration.

To confirm this path, we conducted a quick modification test by adding a 2 kg mass block to the high-voltage harness bracket. This altered the system’s mass and stiffness, shifting its natural frequency and reducing the resonance amplitude. The results were immediate: subjective evaluation indicated a marked reduction in booming noise, and objective measurements showed the 150 Hz noise at the driver’s ear decreased by 4.5 dB(A), with bracket vibration dropping by approximately 10 m/s² in the X-direction. This validated that the bracket resonance was the key contributor.

With the problem root cause identified, we proceeded to develop a permanent solution. The goal was to redesign the bracket to shift its natural frequency away from the excitation frequency. For hybrid electric vehicles operating in hybrid direct drive mode, the engine speed range is controlled by the vehicle control unit. In first gear under light throttle, the shift point to second gear occurs around 2500 r/min. To avoid the 4th-order excitation, we needed to ensure the bracket’s modal frequency was outside the range corresponding to engine speeds up to the shift point. The target frequency \( f_{target} \) should satisfy:

$$ f_{target} > \frac{N_{shift} \times n}{60} + \Delta f $$

where \( N_{shift} \) is the shift point engine speed (2500 r/min), \( n = 4 \), and \( \Delta f \) is a safety margin to account for variations. Calculating the 4th-order frequency at 2500 r/min:

$$ f_{2500} = \frac{2500 \times 4}{60} = 166.67 \text{ Hz} $$

Considering a margin of 10-15 Hz for robust separation, we set a modal frequency target of \( f_{target} \geq 180 \text{ Hz} \). This target became our design guideline for the hybrid electric vehicle’s high-voltage component mounting system.

We then constructed a finite element (FE) model of the bracket system to simulate and optimize its dynamics. The model included the hybrid transmission assembly, motor controller, PDU, high-voltage harness brackets, and the firewall attachment area. Shell elements (5 mm size) were used for sheet metal parts, and bolt connections were modeled with rigid elements. The constrained modal analysis of the initial design predicted a first flexible mode at 159 Hz, close to the test value of 155 Hz, verifying model accuracy. The mode shape involved bending of the bracket legs and rocking of the PDU.

The optimization aimed to increase stiffness without significantly increasing mass or compromising packaging constraints. The strain energy distribution from the FE analysis highlighted areas of high flexibility, primarily the bracket legs and the base plate. We proposed three modifications: 1) Increasing the thickness and width of the bracket legs, 2) Adding reinforcing ribs to the base plate, and 3) Lowering the overall height of the bracket by 10 mm to improve geometric stability. The stiffness increase can be conceptually understood from the beam bending stiffness formula:

$$ k \propto \frac{E I}{L^3} $$

where \( E \) is Young’s modulus, \( I \) is the area moment of inertia, and \( L \) is the length. By increasing the cross-sectional dimensions (increasing \( I \)) and shortening the leg length \( L \), we significantly boosted \( k \). Since natural frequency \( f_n \) is related to stiffness \( k \) and mass \( m \) by:

$$ f_n = \frac{1}{2\pi} \sqrt{\frac{k}{m}} $$

increasing \( k \) while keeping \( m \) relatively constant raises \( f_n \). Our FE simulations iterated through several designs, and the final optimized bracket design achieved a predicted modal frequency of 186 Hz, meeting the 180 Hz target. A comparison of key parameters is shown below:

| Parameter | Original Design | Optimized Design | Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| First Modal Frequency (Hz) | 159 (FE) / 155 (Test) | 186 (FE) | +27 Hz (FE) |

| Leg Thickness (mm) | 2.0 | 2.5 | +25% |

| Leg Width (mm) | 30 | 40 | +33% |

| Bracket Height (mm) | 120 | 110 | -8.3% |

| Added Reinforcing Ribs | None | 2 ribs | New |

| Approximate Mass (kg) | 1.2 | 1.3 | +8.3% |

Prototype brackets were manufactured based on the optimized design and installed on three test vehicles. We first conducted modal tests on the installed system, which confirmed the frequency shift: the measured modal frequency was now 190 Hz, slightly higher than the simulation, likely due to conservative modeling of boundary conditions. This successfully moved the resonance away from the 4th-order excitation band for the critical engine speed range.

Comprehensive on-road tests were then performed under the same conditions that initially provoked the booming noise. Subjective evaluations by multiple engineers confirmed the complete elimination of the objectionable booming sound in the hybrid direct drive first-gear acceleration from 2000 to 2300 r/min. Objective data corroborated this improvement. As shown in the comparative table below, the 4th-order noise level at the driver’s ear dropped significantly, and the bracket vibration at 150 Hz was drastically reduced.

| Metric | Condition | Original Bracket | Optimized Bracket | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driver’s Ear SPL @ 150 Hz (dB(A)) | Acceleration (2200 r/min) | 56.0 | 53.0 | -3.0 dB(A) |

| Constant Speed (2200 r/min) | 55.5 | 52.5 | -3.0 dB(A) | |

| Bracket Vibration @ 150 Hz (m/s²) | X-direction | 16.0 | 7.5 | -8.5 m/s² |

| Z-direction | 12.5 | 6.0 | -6.5 m/s² | |

| Overall Booming Perception | Subjective Rating (1-10, 10=worst) | 8 | 2 | Major improvement |

The reduction of 3 dB(A) in the 4th-order noise component represents a perceptible and meaningful improvement in cabin quietness. The vibration data shows that the resonance peak at 150 Hz was essentially flattened, confirming that the bracket no longer amplified the engine excitation. This case underscores the importance of considering the dynamic behavior of all structural components, especially those unique to hybrid electric vehicles like high-voltage harness supports, during the NVH development phase.

In conclusion, our investigation successfully diagnosed and resolved an acceleration booming noise issue in a hybrid electric vehicle. The problem was traced to a resonance between the engine’s 4th-order excitation and the natural frequency of the high-voltage harness bracket system. Through a combination of experimental modal analysis, operational data measurement, and finite element simulation, we identified the root cause and established a target modal frequency based on the hybrid electric vehicle’s control strategy. The optimized bracket design, featuring increased stiffness through geometric changes, shifted the modal frequency from 150 Hz to 190 Hz, effectively decoupling it from the critical excitation. This led to a 3 dB(A) reduction in the offending 4th-order booming noise, enhancing the vehicle’s NVH performance.

This experience offers several key takeaways for the development of hybrid electric vehicles. First, the integration of high-voltage systems introduces new structural paths for noise transmission; their brackets and mounts require careful dynamic tuning just like traditional powertrain mounts. Second, the operating profiles of hybrid electric vehicles, with specific engine speed ranges in various drive modes, must inform the frequency avoidance strategies for component modal targets. The formula \( f_{target} > (N_{shift} \times n)/60 + \Delta f \) provides a rational basis for setting such targets. Third, diagnostic tools like order analysis, band-filtering, and experimental modal testing are indispensable for rapid problem isolation in complex hybrid electric vehicle systems. Finally, collaboration between NVH and packaging/design engineers is crucial to implement stiffness improvements within tight spatial constraints. As hybrid electric vehicles continue to evolve, proactive attention to these aspects will be vital for delivering the refined and quiet driving experience that customers expect from advanced electrified vehicles.

Future work could involve developing generalized design guidelines for the dynamic mounting of high-voltage components in hybrid electric vehicles, potentially creating a database of preferred bracket geometries and materials. Additionally, investigating the interaction between multiple brackets in the high-voltage system and their collective effect on global body modes would be beneficial. The use of active damping solutions or tuned mass dampers for particularly challenging cases might also be explored for next-generation hybrid electric vehicles. Ultimately, the goal is to integrate NVH considerations seamlessly into the early design stages of hybrid electric vehicle platforms, preventing such issues before prototypes are built and ensuring that the quietness benefits of electric propulsion are not compromised by structural resonances.